Philosophy of Managing SLAP Lesions

The role of the biceps/superior labral complex in overhead athletics as well as in daily activities remains an enigma. An intact biceps root appears to be essential for high-level performance in throwing a baseball. That is why SLAP repair is essential in returning a baseball pitcher to his previous level of function. We are not aware of any professional or college baseball pitchers who have returned to their prior level of performance after having their biceps root disrupted by tenodesis, tenotomy, or rupture of the long head of the biceps.

In contrast, we have had college tennis players return successfully after a biceps tenodesis. We know of professional football quarterbacks who have had biceps rupture or tenotomy without any loss of speed, accuracy, or distance in throwing a football.

We have found that, in general, the younger high-performance baseball players that ultimately come to surgery will have one or more of the following 3 surgical lesions:

We believe that, over time, hyperexternal rotation causes symptomatic undersurface fiber failure of the rotator cuff due to repetitive torsional overload. In young throwers who are confirmed arthroscopically to meet the hyperexternal rotation criterion of reaching the contact point of internal impingement in the posteroinferior quadrant, we recommend anterior mini-plication to restrict external rotation by 10° to 15°. Our mini-plication consists of placing 2 sutures to plicate the middle glenohumeral ligament (MGHL) to the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL). We do not use suture anchors to plicate in overhead athletes.

In older baseball pitchers (usually >30 years old), partial articular surface rotator cuff tears (PASTA lesions) may develop over time. These do reasonably well if they are arthroscopically debrided. This is the only category of patient in which we debride rather than repair PASTA lesions, since repair will typically reduce external rotation to such an extent that the pitcher cannot be effective in throwing a fastball.

There seems to be something unique about throwing a baseball at high speeds that requires an intact biceps root. This probably has to do with the extremely high angular accelerations that occur in throwing a fastball. These accelerations produce angular velocities of up to 7,000 degrees per second, which is by far the fastest movement in all of sports. Throwing a football and serving a tennis ball both require totally different kinematics with significantly lower angular velocities than those required to throw a baseball.

One consideration in managing SLAP lesions is the anticipated level of future performance and demand when the patient returns to his or her sport. For example, a 40-year-old man with a SLAP lesion treated with a biceps tenodesis can perform quite well on his recreational softball team or pitching batting practice to his son’s Little League baseball team.

All of the above observations and considerations have influenced our algorithm for the management of SLAP lesions. The one category of patient that absolutely requires repair of a SLAP lesion is the high-performing baseball player who wishes to continue to complete at his current level. In addition, we believe in SLAP repair for all young (<35 years old) overhead athletes (volleyball, tennis, football) who have not had previous surgery.

For virtually all other categories of patients, we usually recommend biceps tenodesis by the technique of tendon-to-bone interference fixation. This recommendation also holds for nonbaseball overhead athletes who have had failure of a previous SLAP repair. In these overhead athletes, biceps tenodesis can return them to high levels of performance. However, in baseball players with failed SLAP repairs, we recommend revision repair of the SLAP lesion.

The only other exceptions are individuals with an unstable shoulder (i.e. Bankart tear and SLAP tear) where repair may improve stability, and a symptomatic spinoglenoid cyst where repair will prevent recurrence of the cyst.

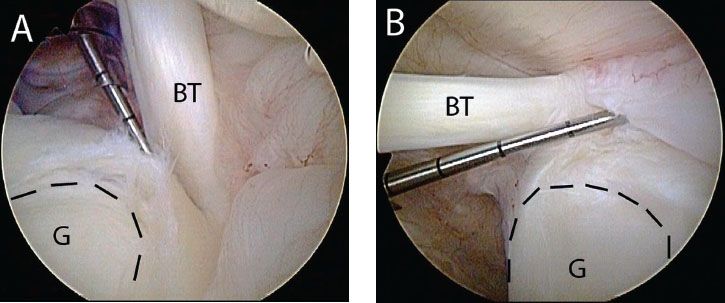

Although SLAP lesions can be disabling to young overhead athletes, we have found that middle-aged and older patients can have symptomatic disruptions of the biceps root attachment, which we call degenerative SLAP lesions. Arthroscopically, these patients do not have a positive biceps tension signs peel-back sign, but they do have a displaceable biceps root when palpating it with a hook probe, as if the biceps does not have a firm attachment into bone (Fig. 15.1). These patients display positive on physical exam and with daily activities, where there is pain when the biceps is placed under tension. The most reliable biceps tension sign in our hands is the O’Driscoll sign, or Mayo Shear sign, as originally described by Dr. Shawn O’Driscoll (Fig. 15.2).

Once patients are beyond the age of competitive high-level sports, usually about 35 years of age, we recommend biceps tenodesis routinely as the treatment for SLAP lesions.

In our experience advancing age and worker’s compensation claims are associated with a poorer outcome following SLAP repair. We recently reported on 55 isloated SLAP repairs at a mean of 77 months (1). Overall, we observed 87% good or excellent results. However, the percentage of good and excellent results among patients >40 years of age (81%) was lower than among patients <40 years of age (97%). The difference was more dramatic with regard to worker’s compensation status where cases without a claim had 95% good or excellent results, compared to only 65% when there was a work claim. Moreover, we recently retrospectively compared primary biceps tenodesis to SLAP repair in individuals over the age of 35 and noted more predictable results following a primary biceps tenodesis (Unpublished Data).

In general, we do not combine the tenodesis with superior labral repair, and we have found that the function usually returns to near-normal levels without the added risk of postoperative stiffness that accompanies labral repair. The only time we combine a tenodesis with a superior labrum repair is when there is a concomitant spinoglenoid cyst that needs to be sealed off with a labral repair or when the superior labral disruption extends so far posteriorly that it creates the possibility of posterior instability.

Figure 15.1 Left shoulder, posterior glenohumeral viewing portal. A,B: A probe introduced from an anterior portal is used to demonstrate two different examples of a displaceable biceps root. The dashed black lines outline the glenoid. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree