Periacetabular Osteotomy and Femoral Osteotomy

Eduardo N. Novais

John C. Clohisy

THE BERNESE PERIACETABULAR OSTEOTOMY

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is associated with structural deformity of the acetabulum that creates mechanical dysfunction and has been recognized as a major factor in the etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip joint (1,2,3). Symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in the congruous dysplastic hip is usually treated by realignment pelvic osteotomy. Although proximal femoral osteotomies alone are utilized less for stabilizing hips with residual acetabular dysplasia (4), femoral osteotomies may be indicated in association with a pelvic osteotomy in cases of severe hip deformity (5). Several techniques of periacetabular osteotomies have been proposed to reorient the dysplastic acetabulum and normalize the mechanics of the hip. Single innominate osteotomy (6) is insufficient to restore joint stability in more complex and severe dysplasia in the adult population. Spherical and rotational acetabular osteotomies (7,8,9) are reported to provide excellent coverage of the femoral head. However, the small size of the acetabular fragment may introduce difficulty with stable fixation, delay patient ambulation, and compromise the blood supply to the acetabular fragment (10).

In 1988, Ganz et al. (11) described the polygonal-shaped Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) that has the advantages of a relatively large and yet mobile acetabular fragment. The Bernese PAO allows correction in multiple planes and rigid fixation while preserving the blood supply to the acetabulum (12), the abductor muscles (13), and the posterior column, which permits early partial weight bearing. The Bernese PAO has become the most widely used acetabular reorientation osteotomy in North America for the mature dysplastic hip (5,14,15,16,17,18,19,20).

Indications and Contraindications

The goals of the Bernese PAO are to reorient the dysplastic acetabulum while reducing pain and improving the function of the hip, with the long-term intention of slowing the progression or preventing symptomatic end-stage arthritis. The Bernese PAO is typically indicated for the treatment of symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in the adolescent and young adult, although it has also been applied for the treatment of severe acetabular retroversion leading to femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). The recommendation to proceed with a Bernese PAO is based on several clinical and radiographic factors. Age is a limiting factor: because the Bernese PAO crosses the posterior aspect of the triradiate cartilage, the procedure is controversial in patients with an open triradiate cartilage. Upper limit of age is controversial although older age at surgery and higher degree of secondary osteoarthritis are recognized as risk factors for PAO failure (18). Specifically, young (younger than 40 years), healthy patients with well-preserved hip motion and a congruous hip joint should be considered for joint preservation surgery even in the presence of mild secondary osteoarthritis. Contraindications include severe femoral head subluxation with the formation of a pseudoacetabulum, complete dislocation, and end-stage osteoarthritic changes.

Preoperative Preparation

Typically, patients with acetabular dysplasia present with groin pain or lateral or anterior hip pain that is aggravated by upright activities. Physical examination should include an overall assessment of the musculoskeletal system with dedicated attention to the quality of gait, hip range of motion, muscle strength, and provocative maneuvers. Special tests include the anterior impingement test, the apprehension test, and the bicycle test. The anterior impingement test is performed with the patient supine. The hip is flexed to about 90 degrees and is adducted and internally rotated, which approximates the femoral neck and the acetabular rim leading to groin or anterior hip pain if the acetabular labrum is damaged. Pain or a sense of instability may be reproduced with the hip extended, abducted, and rotated outward (apprehension test). With the patient in lateral decubitus, abductor muscle strength can be assessed and the bicycle test reflecting abductor muscle insufficiency can be performed (Fig. 9-1).

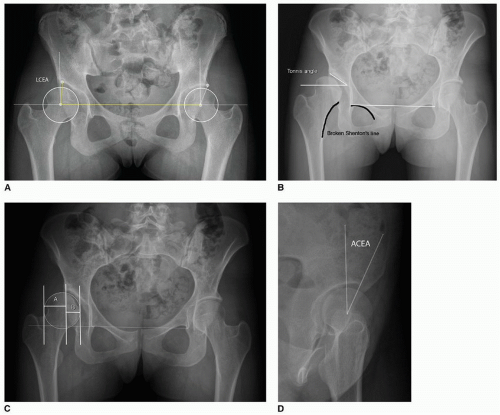

Initial imaging evaluation includes an anteroposterior (AP) pelvic plain radiograph with the patient standing and the beam centered on the femoral heads. The acetabular coverage can be estimated by the lateral center-edge angle (LCEA) of Wiberg (21) (normal is higher than 25 degrees) and by the acetabular index of Tönnis (22) (normal is between 0 and 10 degrees) (Fig. 9-2). The Shenton line is an indicator for subluxation when there is a break greater than 5 mm. The severity of subluxation can be estimated by measuring the extrusion index. Acetabular retroversion is identified by the

crossover sign (23) and by the projection of the ischial spine into the pelvis (24). The false-profile view assesses the anterior coverage of the femoral head by measuring the anterior center-edge angle (ACEA; normal is higher than 20 degrees) (25). A lateral radiograph of the proximal femur gives information about the sphericity of the femoral head and the head-neck offset that can be quantitatively evaluated by the alpha angle and the head-neck offset ratio (26). Functional radiographs with the hip in abduction/internal rotation assess the congruency of the hip. Diagnosis of acetabular dysplasia by definition involves relative undercoverage of the femoral head, as measured by any of the following parameters (22,25,26):

crossover sign (23) and by the projection of the ischial spine into the pelvis (24). The false-profile view assesses the anterior coverage of the femoral head by measuring the anterior center-edge angle (ACEA; normal is higher than 20 degrees) (25). A lateral radiograph of the proximal femur gives information about the sphericity of the femoral head and the head-neck offset that can be quantitatively evaluated by the alpha angle and the head-neck offset ratio (26). Functional radiographs with the hip in abduction/internal rotation assess the congruency of the hip. Diagnosis of acetabular dysplasia by definition involves relative undercoverage of the femoral head, as measured by any of the following parameters (22,25,26):

Lateral center-edge angle less than 20 degrees

Tönnis acetabular inclination greater than 10 degrees

Percent coverage less than 80%/extrusion index greater than 20%

Anterior center-edge angle less than 20 degrees

When performing the Bernese PAO, there is a fine balance between undercorrection and overcorrection and the potential for causing secondary FAI. Achievement of optimal acetabular correction following a Bernese PAO is important for long-term clinical success (18). When planning for the radiographic correction of acetabular dysplasia, we recommend the LCEA between 25 and 40 degrees, ACEA between 18 and 38 degrees, Tönnis angle between 0 and 10 degrees, medial offset distance less than 10 mm, postoperative extrusion index less than or equal to 20% and no retroversion sign. It should be noted that optimal correction varies according to the underlying pathomorphology of the hip.

Advanced imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging play a role in both understanding the biomechanical environment of the hip and estimating the prognosis after surgical intervention. Secondary damage to the labrum and articular cartilage may compromise the results of the Bernese PAO; therefore, appropriate imaging is recommended as part of the preoperative planning. The delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of cartilage (dGEMRIC) technique of the dysplastic hip has been shown to correlate well with success or failure of PAO (27).

Technique

We currently prefer epidural and/or general anesthesia for patients undergoing the Bernese PAO. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered, continuous electromyography peripheral nerve monitoring is optional, and a Cell Saver (Haemonetics, Braintree, MA) is used for blood transfusion. Intraoperative fluoroscopy is recommended to evaluate the osteotomy cuts and assists in the acetabular positioning and fixation. The patient is positioned supine on a radiolucent table. The entire lower extremity and the hemipelvis are prepared and draped, and nerve-monitoring leads are placed. The original technique described by Ganz et al. (11) utilized an iliofemoral approach involving extensive abductor dissection and transection of both the indirect and direct heads of the rectus femoris tendon. Since the original description, there have been several reports describing different approaches to perform the Bernese PAO. These include a direct anterior approach without abductor dissection (13) and (more recently) a rectus femoris preserving approach (28) that minimize the morbidity and improve recovery. We typically perform a modified Smith-Petersen approach preserving the abductors. The rectus femoris tendon is preserved in cases where there is more than 90 degrees of flexion and more than 20 degrees of internal rotation preoperatively with no proximal femur head-neck deformity and no full-thickness labral tear on preoperative MRI or in cases where a hip arthroscopy is performed in combination with the Bernese PAO. The incision begins proximally and extends just lateral to the iliac crest and the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) curving distally and laterally to about 10 cm (Fig. 9-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree