Pelvic Fixation for Neuromuscular Scoliosis

Jaysson T. Brooks

Paul D. Sponseller

DEFINITION

Neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS) is a spinal deformity in the coronal plane in patients with abnormal myoneural pathways of the body.16

Pelvic fixation refers to the anchorage of spinal fixation to the sacrum or ilium or both.

ANATOMY

The pelvis can accommodate large screws that aid in the correction of pelvic obliquity while also providing a stable base in long fusion constructs.

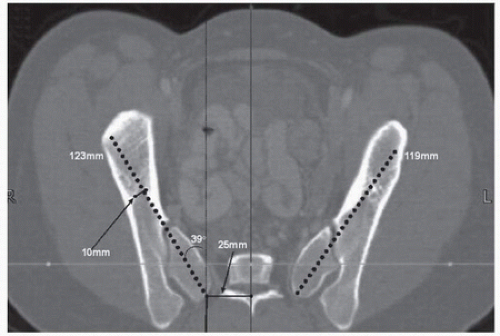

In adolescents, the mean length of the sacral alar iliac (SAI) screw pathway is 106 mm, whereas that of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) to anterior inferior iliac spine pathway (for standard iliac screws) is 123 mm (FIG 1).

The narrowest mean width of the ilium is 12 mm for the right or left side, indicating that the SAI pathway can accommodate large-diameter screws for increased bone purchase.

The average depth below the skin of the SAI screw insertion point is 52 mm, whereas that for the PSIS insertion point7 is 37 mm. This difference of 1.5 cm is important for the patient with neuromuscular deformity who has vulnerable skin because he or she spends most of the time in a recumbent position.

It has been shown that intrapelvic asymmetry between the right and left side is common in patients with NMS.12 A firm grasp not just of normal anatomy but also of the patient’s individual anatomy is vital in placing screws in the right trajectory.

The sacroiliac joint is composed of hyaline cartilage anteriorly and fibrocartilage posteriorly. An SAI screw traverses the hyaline cartilage of the sacroiliac joint 60% of the time.21

PATHOGENESIS

The Scoliosis Research Society has classified the abnormal myoneural pathways that cause NMS into the following categories6:

Neuropathic

Upper motor neuron: cerebral palsy, spinocerebellar degeneration (Friedreich ataxia, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Roussy-Lévy disease), syringomyelia, spinal cord tumors, spinal cord trauma, Rett syndrome

Lower motor neuron: poliomyelitis, traumatic, spinal muscular atrophy, dysautonomia

Combined upper and lower pathologies: myelomeningocele

Myopathic

Arthrogryposis

Muscular dystrophy

Fiber-type disproportion

Congenital hypotonia

Myotonia dystrophica

NATURAL HISTORY

The rates of spinal deformity are high in patients with NMS, including 20% to 70% of patients with cerebral palsy (depending on the amount of trunk control), 60% of patients with Friedreich ataxia, 80% of patients with spinal muscular atrophy, 86% of patients with familial dysautonomia, 50% to 90% of male patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and nearly 100% of patients with traumatic quadriplegia or thoracic level paraplegia before skeletal maturity.4

Unlike adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, most curves in patients with NMS tend to progress.

Pelvic obliquity of 15 degrees or more in patients with NMS will likely worsen after spinal fusion if pelvic fixation is not included as part of the instrumentation construct.18

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The importance of understanding a patient’s baseline function cannot be understated.

Patients with NMS have a wide range of motor and sensory function. Knowledge of this fact is important for postoperative comparison. This baseline should be recorded in the chart, and the patient should be reexamined immediately before surgery. Does he or she move the toes to command or only spontaneously? Is he or she able to ambulate? These questions should be answered by physical examination before surgery begins.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

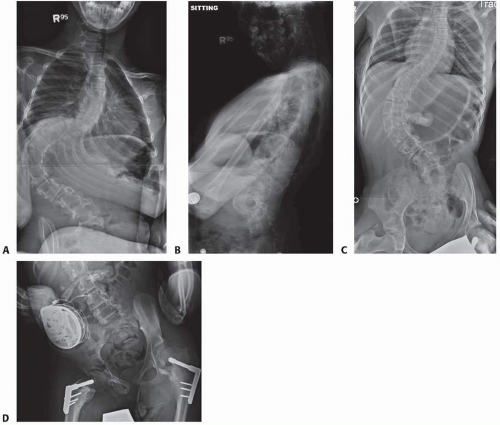

Standard posteroanterior and lateral 3-foot upright scoliosis radiographs (FIG 2A,B) should be obtained.

The rigidity of the curve is assessed by obtaining traction or fulcrum radiographs (FIG 2C).

Pelvic obliquity, sagittal alignment, and the status of the patient’s hips are assessed to help with positioning of the patient on the day of surgery (FIG 2D).

If a baclofen pump is present, the side it is on should be identified to help with the surgical approach.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

It is important to make sure that the patient’s scoliosis is truly neuromuscular and does not fall in other categories such as congenital, idiopathic, or syndromic scoliosis.

Congenital scoliosis is caused by a failure of vertebral formation or segmentation during the fourth to fifth week of gestation. Syndromic scoliosis is discerned by certain pathognomonic features of the suspected diagnosis such as the ligamentous laxity, arachnodactyly, and dolichostenomelia seen in Marfan syndrome.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Bracing

Bracing in patients with NMS is ineffective in preventing progression of the curve and resultant pelvic obliquity.22

If bracing is used, it is often a soft thoracolumbosacral orthosis to help with sitting balance for a flexible curve.

Additional nonoperative interventions include sitting supports, custom seating, and functional sitting programs.9

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Posterior spinal fusion has not been shown to prolong the life of patients with NMS, but it often increases the quality of life through improving trunk balance, sitting position, and comfort; through correction of pelvic obliquity; and by prevention of further progression of their curve.20,24

Historically, fusion to the pelvis was thought to be difficult with associated poor outcomes; however, major advances in spinal fusion techniques have improved outcomes significantly.

In the 1980s, Luque14 introduced segmental spinal instrumentation using sublaminar wires to better control progressive deformity in patients with postpoliomyelitic scoliosis.

The Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation system8 further expounded on Luque’s findings by adding hooks and pedicle screws to the construct and introducing the concept of derotation of the spinal deformity.

In 1988, Allen and Ferguson1 introduced the Galveston technique, involving fixation to the pelvis using an L-shaped rod inserted at the PSIS and placed between the inner and outer tables of the ilium. The Galveston technique improved caudal fixation in long fusions and brought to the forefront the importance of pelvic fixation.

In 1989, Bell et al3 built on the Galveston technique with the unit rod, which was one continuous rod with precontoured bends for kyphosis and for fixation to the pelvis. It was developed to counteract translation of one rod with

respect to the other and to resist rotation of the pelvis around the caudal ends.

The iliosacral screw11 was a natural progression and provided increased caudal purchase because it traversed both cortices of the ilium before entering the S1 pedicle. Its main disadvantage was the extensive soft tissue dissection required to place it in the correct position.

The most recent development in pelvic fixation is the SAI screw.

Its start point is on the sacrum, avoiding the extensive soft tissue dissection needed to use the PSIS as a start point.

As described by McCord et al,17 the stiffness of a construct connected caudally to SAI screws is greatly increased because of the marked anterior extension past the lumbosacral pivot point.

The start point for the SAI screw is 1.5 cm deeper than that the unit rod, avoiding many of the complications associated with the latter, such as prominence and backout.

Implants used for SAI fixation may include standard large screws, cannulated screws, and favored-angle screws. Some have a smooth shank and others have a dual-lead thread.

Preoperative Planning

The decision to fuse to the pelvis depends on the curve pattern and preoperative trunk control. Curves with an apex above the thoracolumbar junction and an end vertebra above L4 may not require fusion to the pelvis. Patients with NMS who have a reasonable ability to sit independently with a balanced pelvis may not require fusion to the pelvis, especially if it would limit their function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree