Pcl Reconstruction Using The Tibial Inlay Technique

Yaw Boachie-Adjei

Mark D. Miller

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF PCL INJURY

History

Patients may report a “dashboard injury” mechanism, in which the patient’s bent knee or shin strikes a fixed surface such as a dashboard. Another mechanism of injury is knee hyperflexion, often during athletics when athletes fall on their knee with their foot plantar flexed. This may overload the quadriceps mechanism. These injuries may or may not be accompanied by an audible “pop.”

Physical Examination

Effusion: An acute hemarthrosis is often present, but is usually not as remarkable as the effusion seen in an acute anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury.

Range of motion: This is often decreased secondary to effusion, pain, and general instability.

Quadriceps tone: This should be noted, as it may be decreased in patients with a chronic tear. This may also be related to posterior tibial subluxation.

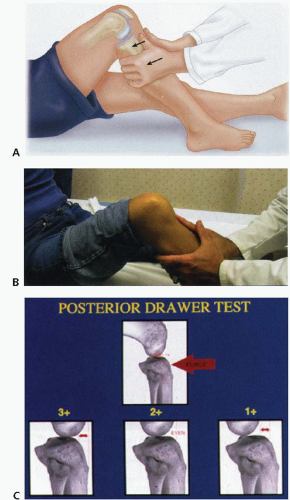

Posterior drawer test/tibial station: This is the gold standard test for PCL injury. The point of the anterior tibia should be carefully assessed in relation to medial femoral condyle. This allows grading of PCL injury (Fig. 75.1A-C).

Normal: At 90° of knee flexion, the tibia should lie 1 cm anterior to the femoral condyles

Grade I: Using the normal side for comparison, a 0.5-cm difference in relative posterior translation

Grade II: The anterior surface of the tibia and femoral condyles is flush (>1 cm of relative posterior translation)

Grade III: The tibia can be translated 1 cm posterior to the anterior femoral condyles. Grade III instability usually represents a combined PCL-posterolateral corner (PLC) injury

Quadriceps active test: This test is performed by flexing the patient’s knee to 90°, while stabilizing the foot and thigh. The patient then contracts the quadriceps while the examiner evaluates the knee for anterior tibial translation. A positive test is indicative of PCL injury.

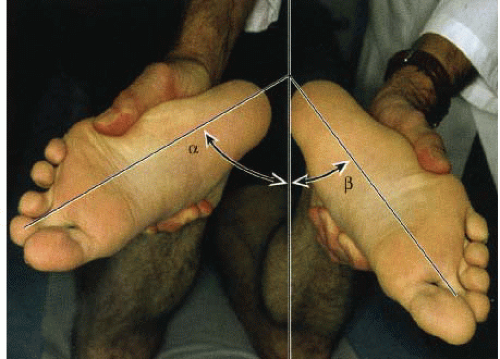

External rotation asymmetry: With the patient prone, grasp their heels, flex their knees up (to 30° and then 90°), and externally rotate their feet. If there is more than 15° of asymmetry in tibial external rotation, there may be a PCL and/or PLC injury that needs to be addressed. Tests should be done at both 30° (to assess PLC alone) and 90° (to assess PCL and PLC) of knee flexion. If asymmetry is present at both positions, a combined PCL-PLC injury is likely. A comprehensive ligamentous examination should be performed to rule out other injuries (Fig. 75.2).

Lachmans test: This is an important test to assess ACL injury.

Varus and valgus stress testing: Should also be done to rule out lateral collateral ligament and medial collateral ligament injury. This is particularly concerning if there is an opening in full extension.

Imaging

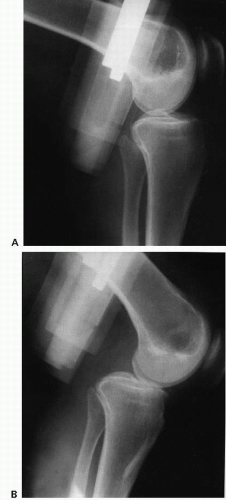

Plain radiographs: Flexion weight-bearing posteroanterior radiographs allow assessment of arthritis and offer a good view of the intercondylar notch. Look for bony avulsion, tibial plateau fracture, and fibular head fracture, indicative of PLC injury. Chronic PCL injuries may be associated with medial compartment arthrosis. Lateral view to look for relationship between the tibia and the femur (A/P translation, rotation). Patellar sunrise view allows evaluation of patellofemoral arthrosis, which is also associated with a chronic PCL injury. Long-leg cassette view: This is a view taken that images from the hip to the ankle and should be considered if there is any question regarding mechanical alignment. Telos stress radiographs: 15 daN of stress is applied to each tibia and radiographs are taken. The normal side (Fig. 75.3A) is compared with the injured side (Fig. 75.3B). This is a standardized and accurate way to distinguish between different types of PCL lesions and permit grading of posterior knee laxity in the PCL-deficient knee.

FIGURE 75.1. A-C: Posterior drawer test. (From Miller MD, Cole BJ, Cosgarea A, et al. Operative Techniques: Sports Knee Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008, with permission.) |

FIGURE 75.2. External rotation asymmetry. (From Miller MD, Cole BJ, Cosgarea A, et al. Operative Techniques: Sports Knee Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008, with permission.) |

MRI: This is another very useful tool. It aids in evaluation of associated injuries. Other soft-tissue/cartilage/bony injuries about the knee greatly affect the approach to treatment of PCL injuries. It is helpful in imaging (Fig. 75.4); other ligaments, extensor injury, menisci, and articular injury.

Decision Making

Historically, the natural history of the disrupted PCL has been debated. Traditionally, most authors have recommended nonoperative treatment of isolated PCL injuries. Many claim that untreated patients progress with minimal symptoms. Indeed, many patients remain symptom-free despite the lack of a PCL, but it has been shown that

articular cartilage degeneration may be accelerated in the patellofemoral compartment and medial compartments. Pain, aching, and effusions may be secondary symptoms, but may not present until several years after PCL injury. Increasing ligamentous laxity does not correlate with severity of any symptoms.

articular cartilage degeneration may be accelerated in the patellofemoral compartment and medial compartments. Pain, aching, and effusions may be secondary symptoms, but may not present until several years after PCL injury. Increasing ligamentous laxity does not correlate with severity of any symptoms.

Classification of PCL injury: Based on both chronicity and severity of injury.

Chronicity

Acute: Injury less than 3 weeks old.

Chronic: Injury greater than 3 weeks old.

Severity

Grades I/II/III: This can be obtained from the posterior drawer test and assessing the tibial station.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative Treatment

Indications for nonoperative treatment include chronic injury in older less active patients. Isolated grade I or II injury, PCL tears from a hyperflexion mechanism will often tear only the larger anterolateral band, whereas the posteromedial band remains intact. This type of injury may spare secondary restraints. Nonoperative treatment may be indicated in this case.

Conservative management consists of early brace management followed by a quadriceps strengthening program. It is important to protect the knee from posterior translation. Athletics are typically restricted until 90% of the quadriceps strength is regained.

Operative Treatment

Indications for operative treatment include

Acute injuries

Isolated grade III injury

Active young patients (especially those with symptomatic grade II injuries)

“Physiologically” young patients

Symptomatic chronic grade II or III injury that has failed rehabilitation (includes older patients)

PCL injury combined with any of the following:

PLC injury (loss of secondary stabilizer to posterior displacement)

ACL injury

Grade III MCL injury

Bony avulsion injury

Timing

Timing of PCL reconstruction depends on the associated pathology and presence of bony injury. In the presence of a PLC injury, acute (<3 weeks) treatment may not be indicated, as there may still be significant soft-tissue swelling from the injury. If a bony injury is present, this may be fixed acutely, with PLC reconstruction done a few weeks later.

TECHNIQUE

Positioning

The lateral decubitus position is used for the open tibial inlay approach (Figs. 75.5 and 75.6). The contralateral well leg should be padded (Fig. 75.6A). An ankle-foot orthosis type holder may be used to hold the surgical extremity (Fig. 75.5). Position the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the operative leg up (Fig. 75.6B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree