Chapter 12 Patient Education and Health Literacy

• I had this one patient with neck and arm pain and she seemed really stressed out about the problem and worried that she might get worse with therapy. So I decided to keep her initial home exercise program really simple at first and I gave her only three very mild stretching exercises to do. Well, the next session she came back and I asked her to show me her exercises like she was doing them at home. I couldn’t believe what I saw!! I could hardly recognize what she was doing! From now on, I am going to go very slowly when teaching exercises—I am going to have the patient show me the exercises several times in therapy and make sure that they have written home programs with pictures and simple explanations on them. I think I rushed my teaching with this patient and was too timid in my instructions because she was so worried about getting worse.1(p 308)

• If I have a hard time finding time to do trunk strengthening exercises [that I need to do], then don’t my patients have a hard time finding time to do a home exercise program? I think that therapists, including me, forget that parents who have a child who needs to do a HEP have busy lives and may not have time to do the program with their child. If I can keep this in mind, I think I will have better success when it comes to designing a HEP and having the patient actually do it. Also, when I ask a parent or child if they have been doing the HEP, I have to be prepared for the “no’s” and armed with the “why’s” to do the program and the “how’s” to fit it in.1(p 309)

• Another time I felt good was when I was describing to the patient what was happening with her. I got out the model of the spine and showed her the area from which the problem stemmed. I educated her on the discs and nerve roots. She really seemed to benefit from the discussion and learned a lot. She said it made her understand the purpose of her exercise program and of the treatments we were doing with her. It made me feel good because I felt effective.1(p 309)

Centrality of Patient Education to Effective Clinical Practice and Achievement of Desired Health Outcomes

Scope and Magnitude of the “Literacy Problem” in the United States

Implications of Low Literacy for Individual and Public Health

What can we do to be Effective Communicators and Teachers and Foster Patient Learning?

Developing Appropriate Educational Interventions and Materials

Designing and Evaluating Patient Education Materials: Helping Your Patients to Learn from Written Materials

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Describe the scope and breadth of the “literacy problem” in the United States and accurately identify specific patient populations seen in physical therapy who are at risk for low literacy.

2. Define and distinguish between the following terms: general literacy, literacy domains, literacy levels, health literacy, readability, suitability, and comprehension.

3. Discuss risk factors and behavioral cues that might indicate low health literacy in patients and identify appropriate methods for assessing and addressing their literacy needs to achieve desired educational and health-related outcomes.

4. Describe characteristics of effective verbal and nonverbal communication with patients that can create a shame-free clinical environment, facilitate the development of positive relationships, enhance learning, and foster comprehension.

5. Assess the literacy demands, readability, and suitability of written educational materials developed for patients using selected informal methods or formal tools and instruments.

6. Identify or develop home programs, instructional materials, or media resources that are appropriately designed to meet the learning needs and goals of patients and their care providers.

7. Describe and implement several teaching/learning activities that can link classroom instruction about patient education and health literacy with experiential learning in clinical settings.

8. Describe, design, and implement teaching/learning activities that provide opportunities for reflection and dialogue about patient education and health literacy during clinical experiences.

Centrality of patient education to effective clinical practice and achievement of desired health outcomes

Numerous documents directly related to physical therapy practice and education emphasize the centrality and importance of patient education in the everyday work of physical therapists.2–6 The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) Guide to Physical Therapy Practice2 identifies patient/client instruction as a key component of intervention in the patient/client management model and defines patient/client related instruction as follows: “The process of informing, educating, or training patients/clients, families, significant others and caregivers is intended to promote and optimize physical therapy services. Instruction may be related to the current condition; specific impairments, functional limitations, or disabilities; plan of care; need for enhanced performance; transition to a different role or setting; risk factors for developing a problem or dysfunction; or need for health, wellness, or fitness programs. Physical therapists are responsible for patient/client related instruction across all settings for all patients/clients.”2(p 47) This definition highlights the depth and breadth of a therapist’s responsibility for effective teaching and promoting learning in clinical encounters in a wide variety of practice settings.

In addition, The Joint Commission standards for accreditation of hospitals and other health care organizations require that individual providers and organizations provide effective, “patient-centered” communications to optimize the quality of care delivered and ensure patient understandings and safety.7 Those standards require, among other things, that education provided to patients is based on assessment of patient and family/caregiver needs (both clinical and communication needs), addresses their needs, is appropriate and adapted to the patient’s level of understanding and abilities, and is delivered using a variety of instructional tools or methods, and that patient comprehension of educational information provided is evaluated. During the past decade, as the standards for patient-provider communication have been further developed and elaborated, The Joint Commission has also spearheaded several initiatives in this area that have culminated in reports that highlight the importance of addressing literacy issues and concerns as health care professionals and organizations serve an increasingly diverse and aging citizenry in the United States.8–10

Finally, the new Healthy People 202011 (HP 2020) framework and objectives encourage increased emphasis on health communication and the effective use of information technology to achieve the overarching goals of HP 2020. The broad goals of HP 2020 and selected health communication and information technology objectives are shown in Box 12-1.

Healthy People 2020 Overarching Goals

• Attain high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

• Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups.

• Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.

• Promote quality of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors across all stages of life.

Selected Health Communication and Health Information Technology Objectives

• Improve the health literacy of the population.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always gave them easy-to-understand instructions about what to do to take care of their illness or health condition.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always asked them to describe how they will follow the instructions.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider’s office always offered help in filling out a form.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care providers have satisfactory communication skills.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always listened carefully to them.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always explained things so that they could understand them.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always showed respect for what they had to say.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always spent enough time with them.

• Increase the proportion of persons who report that their health care provider always involved them in decisions about their health care as much as they wanted.

• Increase the proportion of persons whose doctor recommends personalized health information resources to help them manage their health.

Clearly, the time for focused attention on the health literacy of the patients, family members, and care providers we encounter in our daily work as physical therapists is here. Furthermore, as our scope of practice continues to expand in the realms of community-based education, health promotion, and wellness, attention to the health literacy of the larger population of individuals in our society is essential for us to be effective health educators. (See also Chapters 13 and 15.)

Scope and magnitude of the “literacy problem” in the united states

Surprisingly, focused attention on general literacy concerns, and more recently health literacy concerns, in the United States is a relatively recent trend in our history. In response to these concerns, however, the first nationwide assessment of adult literacy, the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), was conducted by the U.S. Department of Education in 1992. That survey and a 10-year follow-up study, the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), revealed a high prevalence of illiteracy and low literacy in the United States.12–14 The NALS and the NAAL defined general literacy as, “Using printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.”14

In the 2003 NAAL, the literacy skills of a representative sample of about 20,000 adults (defined as 16 years or older) were measured in three domains. These domains represent three functional tasks that individuals would need to access, understand, and use information (Box 12-2).

Box 12-2 Functional Tasks Needed to Access, Understand, and Use Information

• Prose tasks: The knowledge and skills needed to understand and use information from text materials such as newspapers, magazines, books, brochures, etc.

• Document tasks: The knowledge and skills needed to find, interpret, and use information from documents such as applications, forms, maps, transportation schedules, charts, etc.

• Quantitative tasks: The knowledge and skills required to read, interpret, and work with numerical information and apply mathematics to calculate or reason numerically such as reading nutrition labels and calculating calories, computing restaurant bills and tips, balancing a checkbook, etc.

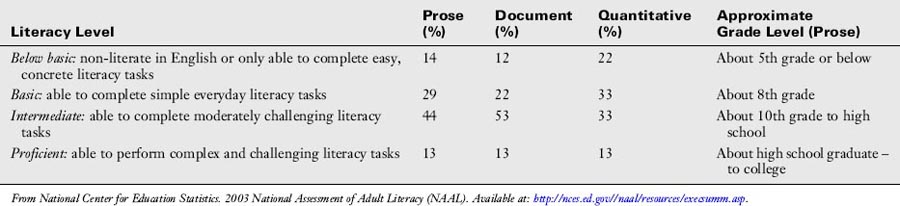

In the NAAL, the degrees of difficulty for literacy tasks in these the domains were identified as below basic, basic, intermediate, or proficient. Brief descriptions of these levels and the findings from the 2003 NAAL are shown in Table 12-1. Note that 55% of the sample population was determined to be at the basic or below basic level for quantitative tasks; 43% of the sample population was determined to be at the basic or below basic level for prose tasks; and 34% of the sample population was determined to be at the basic or below basic level for document tasks. If you think about the kinds of tasks patients are required to do in the course of clinical care, those individuals at the basic or below basic level (55% in the quantitative category, 43% in the prose category) might experience significant difficulty completing intake forms, comparing drug plans, identifying what they may or may not drink or eat before a medical test, or following written instructions on prescriptions to determine correct dosages. Even those individuals at the intermediate level (53% in the document category, 44% in the prose category) may have difficulty fully understanding insurance forms and plans, consent forms, and medication and other health care instructions.

Table 12-1 Descriptions of Literacy Levels and Findings from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy

In the 2003 NAAL, a health literacy scale was included, and tasks specific to health literacy were assessed nationwide for the first time. The development of this scale and the tasks included in the assessment were guided by a definition of health literacy that had been adopted by the Institute of Medicine15 and used by Healthy People 2010.16 Health Literacy was defined as, “[t]he degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”15(p 32) The health literacy tasks in the NAAL were distributed across three domains of health care services or information:

1. Clinical care (e.g., understanding health or medication dosing instructions or filling out a form)

2. Prevention services and information (e.g., following guidelines for prevention services such as immunizations)

3. Navigation of the health care system (e.g., understanding an insurance plan or determining eligibility for assistance)

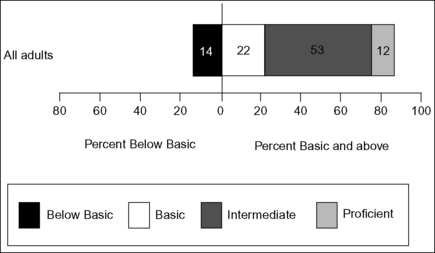

The health literacy results of the NAAL were published in 200617 and underscored the need for health care professionals, health care organizations, and the health care system as a whole to “take health literacy seriously.”18,19 The overall findings are shown in Figure 12-1 and indicated that 36% of adults in the sample (representing more than 75 million adults) had basic or below basic levels of health literacy: this means their overall literacy skills were at about an 8th-grade level or below. Of these individuals, 14% were measured at the below basic level and would be considered functionally illiterate when dealing with health information. Fifty-three percent of the individuals in the sample (representing about 114 million adults) were rated in the intermediate level of health literacy (about 10th- to 12th-grade level), and only 12% of the population was considered proficient (see Figure 12-1). Two percent of the individuals in the NAAL sample (representing about 4 million adults) had language barriers that prevented participation and were unable to be measured. Those individuals were categorized as nonliterate in English, although it is important to note that they may be literate in their primary language. The findings also identified several risk factors and populations at risk for low health literacy, and these will be discussed further in the next sections of this chapter.

Figure 12-1 Percentage of adults in each health literacy level.

(From National Center for Education Statistics. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences, 2006.)

The good news that emerges from these rather disturbing findings is that there has been increasing attention given to addressing the health literacy problem in the United States, and many initiatives have been undertaken to make health information more accessible, clear, and understandable in all forms (oral, visual, and textual) so that a much larger percentage of the population can evaluate, use, and benefit from the information provided by health care professionals. There is a clear realization that we must not only address health literacy concerns but also move as rapidly as possible toward solutions at the level of individual providers, health care organizations and systems, and health policy makers. This vision and commitment are captured in a summary in the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy: “By focusing on health literacy issues and working together, we can improve the accessibility, quality, and safety of health care; reduce costs; and improve the health and quality of life of millions of people in the United States.”20

Implications of low literacy for individual and public health

There is a large and growing body of literature that suggests links between low literacy and poor health outcomes, but it is beyond the scope or intent of this chapter to review all of that literature. A report from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHCRQ), however, provides a review of evidence and a summary of the many links between low literacy and poor health outcomes, health status, and health disparities.21,22 What we do know from the literature is that low health literacy can lead to low health knowledge and understanding and thus less healthy behaviors, safety concerns for patients and others involved in their care, disparities in access to and quality of care delivered, and greater health costs for individuals and society. We also know that “literacy skills are a stronger predictor of an individual’s health status than age, income, employment status, educational level, and racial or ethnic group.”23,24 Given the high prevalence of low health literacy skills in our population and the health and societal consequences associated with low literacy, it is incumbent on all health professionals to respond. We must do this in order to address the patient’s right to and need for clear communication about their health, to reduce the potential for error and increase patient safety, to enhance the quality of health care services, and to contain health care costs.

What can we do to be effective communicators and teachers and foster patient learning?

Recognizing populations at risk, risk factors, and health literacy challenges

Based on the findings from the health literacy component of the 2003 NAAL,14,17 we know several groups of individuals are at higher risk for health literacy concerns (Table 12-2).

Table 12-2 Individuals at Higher Risk for Health Literacy Concerns

| Population | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Older adults | Adults who are 65 years old or greater had lower average health literacy than those who were younger. The physical changes associated with aging are likely to contribute to or compound this problem—visual changes, hearing loss, cognitive changes, etc. More than 60% of individuals 65 years or older were at the basic or below basic level. |

| People with low incomes or living at or below the poverty line | Adults living at or below the poverty line had lower average health literacy than those above the poverty line. |

| People with less than a high school degree | Average health literacy increases with each higher level of education attained starting with high school graduates or individuals with a GED. Below basic health literacy comprised 49% of adults who had never attended or completed high school. |

| Racial and ethnic minorities | Hispanic adults had lower average health literacy than black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and multiracial adults. Whites and Asian/Pacific Islander adults had higher average health literacy than all of those groups. |

| Non-native speakers of English | Individuals who spoke only English before starting school had higher average health literacy than those who spoke English and another language or only another language before starting school. |

| Male Gender | Men had lower average health literacy than women. Sixteen percent of men were in the below basic category compared with 12% of women. |

| Persons on Medicare, Medicaid, or uninsured | Adults who received Medicare or Medicaid and adults who had no insurance had lower average health literacy than adults who were covered by other types of insurance (employer provided, privately purchased, or military). |

| Individuals with chronic disease or disability | Adults who had chronic disease or disability had lower average health literacy than those who did not. |

A quick review of the list in Table 12-2 suggests that many of the individuals we see in our clinics on a daily basis may fall into several of these groups or present with several risk factors for low health literacy concurrently. Being aware of the potential for health literacy concerns is a first step toward responding appropriately but much more is needed. In the following section, we will discuss several strategies and tools clinicians can use for assessing health literacy.

Assessing health literacy: informal assessments

Physical therapists and rehabilitation and health professionals in general are excellent observers. Combined with our recognition of the prevalence of low health literacy in the U.S. population, we can use our keen observational and interviewing skills to identify clues for low literacy or alert us to “red flags.” Picking up on these clues and identifying red flags will allow us to adapt our educational interventions to better meet the needs of our patients. Table 12-3 provides a list of some red flags that you may have encountered in your interactions with patients. Can you identify others?

Table 12-3 Some Clues and Red Flags that Might Suggest Low Health Literacy

| Behaviors You Might Observe | Things a Patient Might Say | |

|---|---|---|

| Reading behaviors | Lifts texts closer to face when reading Points to and follows text with finger while reading Eyes wander over page without finding central focus Slow reading; asks someone else to read text/form for them Signs forms without reading Struggles with more than one piece of information or paper at a time May get frustrated with multiple forms, leave the clinic or waiting room | “I forgot (lost, broke) my glasses, can you read this to me?” “My eyes are tired, I’ll read this when I get home.” “I’m having trouble seeing.” “The lighting is not good.” “I don’t feel well, will you read this for me?” |

| Self-care behaviors | Unable to name medications, explain why they take them or when/how to take them. Identifies medications by color and size of pill, not by name or reading labels Makes errors or lacks follow-though on self-care instructions such as exercise prescriptions, therapy recommendations, or medication regimens; may appear or be labeled nonadherent/noncompliant Misses appointments or arrives at the wrong times for appointments Resists filling out forms or activity logs; forms are incomplete or incorrectly filled out Waits until illness or problem is advanced before seeking help | “I just put them in my daily/weekly container—I don’t need to know the names of my pills.” “I lost/can’t find my instruction sheet.” (exercise or activity log) “Could you just draw pictures of the exercises for me?” “I lost my appointment card.” “Could I have my appointments on the same days and at the same time?” “I was too busy to get help.” “I don’t have time.” |

| Communication behaviors | Shows signs of nervousness or frustration May not answer questions or incorrectly answer questions; demonstrates differences between what is heard and read Is very quiet, passive Nods head in response to information but doesn’t ask any questions in follow-up Asks a lot of questions, possibly out of context, about information provided previously or in written materials | In response to questions from the health care provider like “Do you understand?” or “Does that make sense?” always answers “Yes” without further questions In response to questions like “Do you have any other questions?” frequently answers “No” |

Data from Area Health Education Clear Health Communication Program, The Ohio State University. You Can’t Tell By Looking: Assessing a Patient’s Ability to Read and Understand Health Information. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University, Office of Outreach and Engagement, 2007.

Some of the behaviors and responses described in Table 12-3 may be due to many patients with low literacy feeling ashamed about their difficulty reading and trying to hide it—even from family members in some cases.25,26 Because of the potential for shame or stigma, patients may also be hesitant to admit to health professionals that they have difficulty reading or understanding health information. Therefore, we need to develop strategies for assessing and addressing literacy concerns by creating clinical environments and encounters that are “shame free” and reduce the potential for embarrassment or humiliation of the patient.

Therapists can use the social history and the subjective portion of their examination to screen for possible literacy concerns for their patients. For example, as you review information available to you in the medical chart, intake forms, or referrals, be alert for the risk factors identified in Table 12-2. If any of those factors are or may be present, then be on heightened alert for the behaviors listed in Table 12-3. It is also important to remember that stress associated with illness, injury, and disability, in and of itself, can create barriers to communication and understanding of complex health information.

As you conduct the subjective portion of the examination, try to ask questions that would get at the potential for literacy problems while being as nonthreatening as possible to the patient. Some suggestions for questions that may be useful and help to open the door for the patient to discuss their abilities in this realm are shown in Box 12-3.

Box 12-3 Ways to Ask “Shame-Free” Questions about Reading Skills

• “Medical terms can be complex and many people find them hard to understand. Do you ever get help from others to fill out forms, read prescription labels, or health instruction sheets?”

• “A lot of people have trouble reading and remembering health information because it is complicated. Is this ever a problem for you?”

• “How happy are you with the way you read?”

• “What do you like to read?” (Most newspapers are 10th-grade level, news magazines are 12th-grade level.)

• “When you have to learn something new, what ways do you prefer to learn the information?” (TV? Radio? Talking with people? Trying it yourself? Reading?)

• “How often do you have somebody help you read hospital materials?”

• “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written communication?”

• “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree