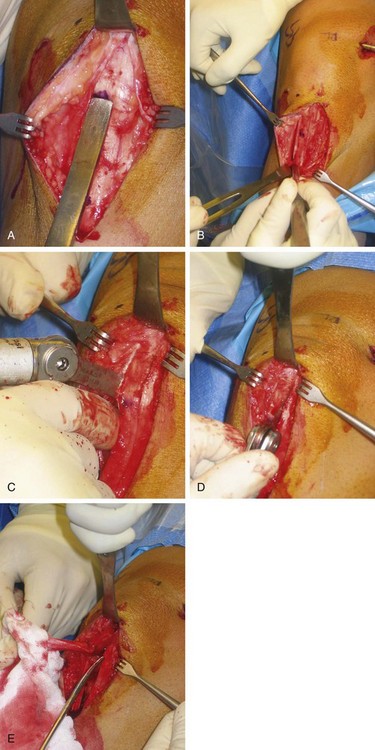

Chapter 72 Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture commonly occurs among both professional and amateur athletes. Because the ACL is the primary restraint to anterior displacement of the tibia on the femur and a secondary stabilizer to tibial rotation, an ACL-deficient knee can lead to meniscal injury, functional instability, and early-onset osteoarthritis.1 These are potentially devastating consequences in certain populations of patients, especially in athletes who participate in cutting or pivoting activities. The ACL is the most frequently torn knee ligament requiring surgical repair, and more than 100,000 ACL reconstructions are performed each year in the United States.2 A variety of decisions must be made when performing ACL reconstruction, including surgical technique, graft source, and graft fixation. Graft options may include autograft (bone–patellar tendon–bone, hamstring, and quadriceps tendon) or allograft (bone–patellar tendon–bone, Achilles tendon, and anterior tibialis tendon) tissue. The bone–patellar tendon–bone autograft has been the most commonly used graft during the last 15 years and is the graft of choice of physicians treating National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1A and professional athletes.3–7 This is because of the graft’s ready accessibility, good mechanical strength, bone healing, and interference screw fixation. One of our primary goals in ACL reconstruction is to reapproximate the native ACL anatomy with respect to tibial and femoral tunnel placement. This anatomy has been well described in the literature. Several surgical techniques for drilling the femoral and tibial ACL tunnels can be used to accomplish this, including transtibial drilling, medial portal femoral independent drilling, outside-in femoral independent drilling, and two-incision ACL reconstruction. This chapter details the surgical technique for anatomic transtibial and medial portal femoral independent endoscopic ACL reconstruction with a bone–patellar tendon–bone autograft. • A noncontact injury that occurred during a change-of-direction maneuver, such as pivoting, cutting, or decelerating. • The patient may have noted knee hyperextension during an awkward landing. • A “pop” was heard or felt during the event. • Acute onset of significant swelling that often developed in minutes to hours. • A sensation of instability limits the ability to return to play. • The patient reports catching or locking (signifies meniscal disease, stump impingement, or loose bodies). • The patient’s age, history of anterior knee pain or patellar instability and other previous knee injury, and contralateral knee instability are critical to decision making. At this time a tourniquet is placed and the thigh is secured in a leg holder for added stability. The contralateral leg is positioned in a well-padded foot holder with the knee and hip flexed to protect the peroneal nerve. The foot of the operating room table is then dropped, and the waist is flexed to diminish the amount of lumbar extension (Fig. 72-1). The leg is prepared and draped in sterile fashion while preoperative antibiotics are administered. The longitudinal incision for the bone–patellar tendon–bone harvest starts at the most distal aspect of the patella, just medial to the midline, coursing distally to 2 cm below the tibial tubercle (Fig. 72-2). Alternatively, the use of transverse skin incisions over the lower pole of the patella and tibial tubercle may provide a more cosmetic skin scar and potentially avoid injury to the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve. Examination under anesthesia is completed as previously described. Of note, if the examination under anesthesia is unclear regarding ACL rupture, diagnostic arthroscopy is performed before harvesting of the bone–patellar tendon–bone graft.5 Box 72-1 outlines the surgical steps of this procedure. At this point, an oscillating saw is used to make first the tibial then the patellar bone plug. With use of the nondominant thumb to stabilize the saw and the index finger to protect the graft between the inner and outer portion of the graft (Fig. 72-3), the tibial cortex is scored longitudinally on profile to remove an equilateral triangle of bone. This leaves a maximal amount of bone around the tibial tubercle and remaining patellar tendon to minimize the risk of postoperative complications, such as patellar tendon avulsion or tubercle fracture. The distal transverse tibial crosscut is made with the saw held at a 45-degree oblique angle to the cortex by use of the corner of the blade on each side of the plug, but the tibial bone plug is left in place at this time. The patellar tendon bone plug is then made in a trapezoidal shape, with a depth not exceeding 6 to 7 mm to avoid damage to the articular surface. Once again, the proximal transverse crosscut is made at a 45-degree oblique angle to the cortex. The saw is then placed parallel to the medial and lateral edges to complete the patellar bone plug crosscuts. Half-inch and quarter-inch curved osteotomes are now used to carefully mobilize the bone plugs without levering. A lap sponge can be placed around the freed tibial plug to improve traction, and Metzenbaum scissors are used to carefully remove any remaining fat or soft tissues. Once it is freed, the graft is wrapped in a moist sponge and walked to the back table by the operative surgeon, where it is placed in a safe location known to all members of the surgical team.

Patellar Tendon Autograft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Preoperative Considerations

Surgical Technique

Incision

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Specific Steps

1 Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone Graft Harvest

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Patellar Tendon Autograft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction