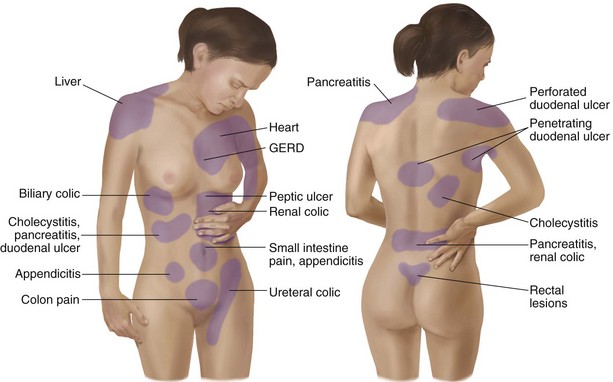

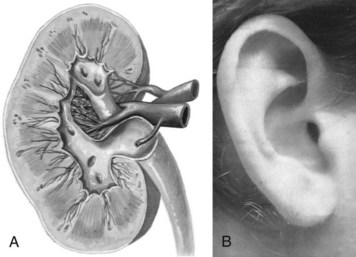

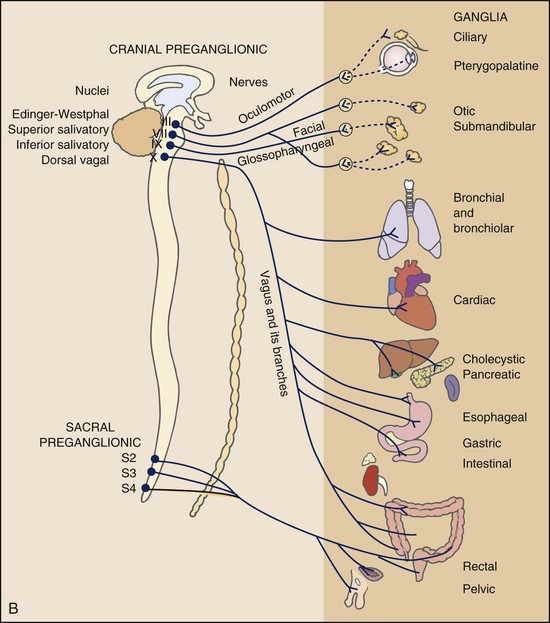

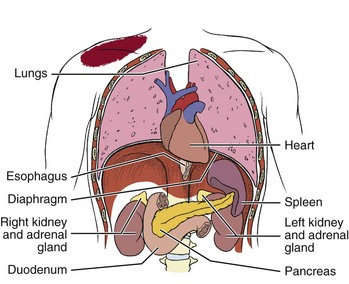

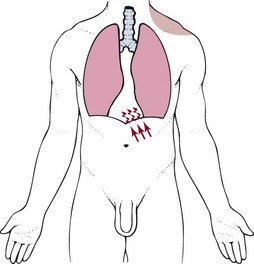

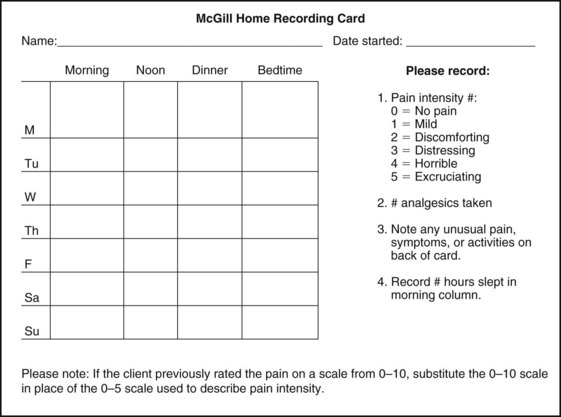

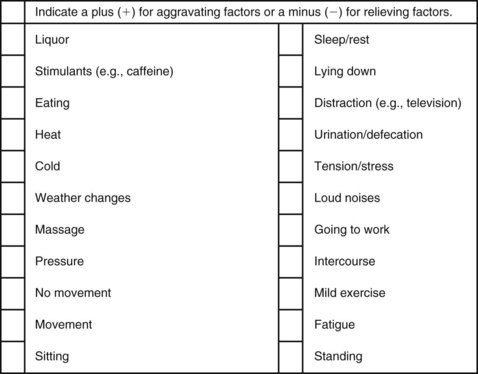

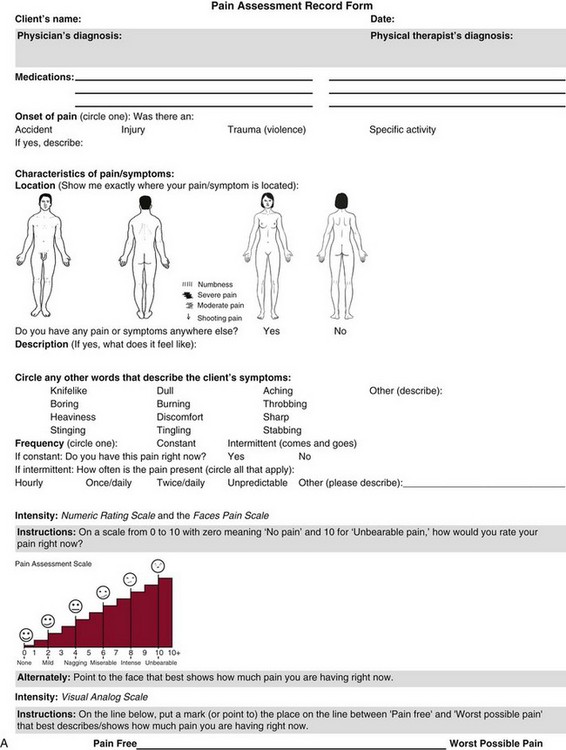

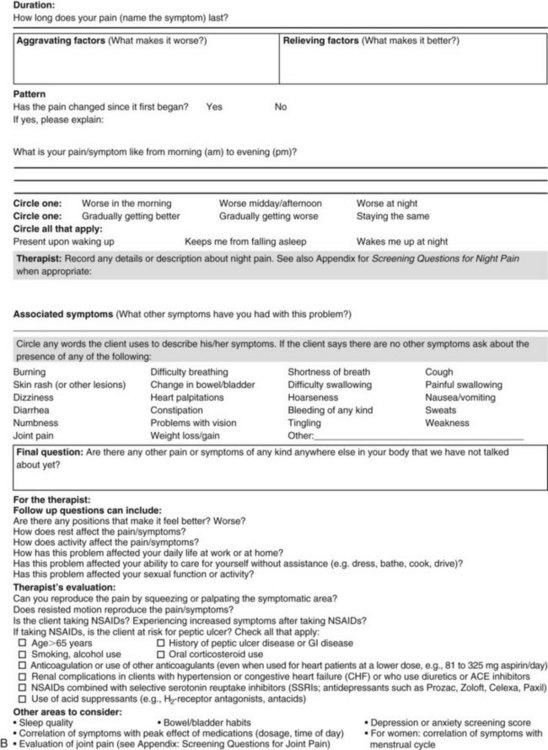

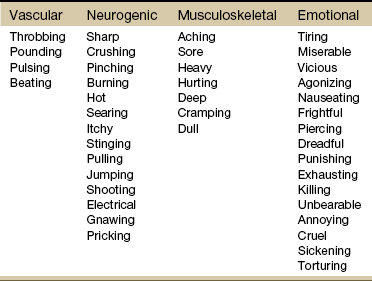

Chapter 3 Pain is often the primary symptom in many physical therapy practices. Pain assessment is a key feature in the physical therapy interview. Pain is now recognized as the “fifth vital sign,”1 along with blood pressure, temperature, pulse, and respiration. This chapter includes a detailed overview of pain patterns that can be used as a foundation for all the organ systems presented. Information will include a discussion of pain types in general and viscerogenic pain patterns specifically. Additional resources for understanding the mechanisms of pain are available.2 This information is then compared with presenting features of primary musculoskeletal disorders that have similar patterns of presentation. Pain patterns of the chest, back, shoulder, scapula, pelvis, hip, groin, and sacroiliac (SI) joint are the most common sites of referred pain from a systemic disease process. These patterns are discussed in greater detail later in this text (see Chapters 14 to 18). The neurology of visceral pain is not well understood at this time. Proposed models are based on what is known about the somatic (nonvisceral) sensory system. Scientists have not found actual nerve fibers and specific nociceptors in organs. Peripheral mechanisms are suspected.3 We do know the afferent supply to internal organs is in close proximity to blood vessels along a path similar to the sympathetic nervous system.4,5 Research is ongoing to identify the sites and mechanisms of visceral nociception. During inflammation, increased nociceptive input from an inflamed organ can sensitize neurons that receive convergent input from an unaffected organ, but the site of visceral cross-sensitivity is unknown.6 Viscerosensory fibers ascend the anterolateral system to the thalamus with fibers projecting to several regions of the brain. These regions encode the site of origin of visceral pain, although they do it poorly because of low receptor density, large overlapping receptive fields, and extensive convergence in the ascending pathway. Thus the cortex cannot distinguish where the pain messages originate from.7,8 Studies show there may be multiple mechanisms operating at different sites to produce the sensation we refer to as “pain.” The same symptom can be produced by different mechanisms and a single mechanism may cause different symptoms.9 Each system has a bit of its own uniqueness in how pain is referred. For example, the viscera in the abdomen comprise a large percentage of all the organs we have to consider. When a person gives a history of abdominal pain, the location of the pain may not be directly over the involved organ (Fig. 3-1). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and other neuroimaging methods have shown activation of the inferolateral postcentral gyrus by visceral pain so the brain has a role in visceral pain patterns.10,11 However, it is likely that embryologic development has the primary role in referred pain patterns for the viscera. Embryologically, the chest is part of the gut. In other words, they are formed from the same tissue in utero. This explains symptoms of intrathoracic organ pathology frequently being referred to the abdomen as a viscero-viscero reflex. For example, it is not unusual for disorders of thoracic viscera, such as pneumonia or pleuritis, to refer pain that is perceived in the abdomen instead of the chest.4 Although the heart muscle starts out embryologically as a cranial structure, the pericardium around the heart is formed from gut tissue. This explains why myocardial infarction or pericarditis can also refer pain to the abdomen.4 Another example of how embryologic development impacts the viscera and the soma, consider the ear and the kidney. These two structures have the same shape since they come from the same embryologic tissue (otorenal axis of the mesenchyme) and are formed at the same time (Fig. 3-2). Multisegmental innervation is the second mechanism used to explain pain patterns of a viscerogenic source (Fig. 3-3). The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is part of the peripheral nervous system. As shown in this diagram, the viscera have multisegmental innervations. The multiple levels of innervation of the heart, bronchi, stomach, kidneys, intestines, and bladder are demonstrated clearly. There is new evidence to support referred visceral pain to somatic tissues based on overlapping or same segmental projections of spinal afferent neurons to the spinal dorsal horn. This concept is referred to as visceral-organ cross-sensitization. The mechanism is likely to be sensitization of viscera-somatic convergent neurons.12 For the first time ever, scientists showed that individuals diagnosed with multiple visceral problems obtained relief from pain in all organ systems with overlapping segmental projections when only one visceral area was treated. In other words, nontreated visceral disease significantly decreased when one viscera of the overlapping segments was addressed. For groups of people with no overlapping segments, spontaneous relief of referred pain was not obtained until and unless all involved visceral systems were treated.12 A third and final mechanism by which the viscera refer pain to the soma is the concept of direct pressure and shared pathways (Fig. 3-4). As shown in this illustration, many of the viscera are near the respiratory diaphragm. Any pathologic process that can inflame, infect, or obstruct the organs can bring them in contact with the respiratory diaphragm. Anything that impinges the central diaphragm can refer pain to the shoulder and anything that impinges the peripheral diaphragm can refer pain to the ipsilateral costal margins and/or lumbar region (Fig. 3-5). Plexuses originate in the neck, thorax, diaphragm, and abdomen, terminating in the pelvis. The brachial plexus supplies the upper neck and shoulder while the phrenic nerve innervates the respiratory diaphragm. More distally, the celiac plexus supplies the stomach and intestines. The neurologic supply of the plexuses is from parasympathetic fibers from the vagus and pelvic splanchnic nerves.4 The plexuses work independently of each other but not independently of the ganglia. The ganglia collect information derived from both the parasympathetic and the sympathetic fibers. The ganglia deliver this information to the plexuses; it is the plexuses that provide fine, local control in each of the organ systems.4 Not only is it true that any structure that touches the diaphragm can refer pain to the shoulder, but even structures adjacent to or in contact with the diaphragm in utero can do the same. Keep in mind there has to be some impairment of that structure (e.g., obstruction, distention, inflammation) for this to occur (Case Example 3-1). The interviewing techniques and specific questions for pain assessment are outlined in this section. The information gathered during the interview and examination provides a description of the client that is clear, accurate, and comprehensive. The therapist should keep in mind cultural rules and differences in pain perception, intensity, and responses to pain found among various ethnic groups.13 Measuring pain and assessing pain are two separate issues. A measurement assigns a number or value to give dimension to pain intensity.14 A comprehensive pain assessment includes a detailed health history, physical exam, medication history (including nonprescription drug use and complementary and alternative therapies), assessment of functional status, and consideration of psychosocial-spiritual factors.15 The portion of the core interview regarding a client’s perception of pain is a critical factor in the evaluation of signs and symptoms. Questions about pain must be understood by the client and should be presented in a nonjudgmental manner. A record form may be helpful to standardize pain assessment with each client (Fig. 3-6). Fig. 3-6 Pain Assessment Record Form. Use this form to complete the pain history and obtain a description of the pain pattern. The form is printed in the Appendix for your use. This form may be copied and used without permission. (From Carlsson AM: Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale, Pain 16(1):87–101, 1983. Used with permission.) If the client has completed the McGill Pain Questionnaire (see discussion of McGill Pain Questionnaire in this chapter),16 the physical therapist may choose the most appropriate alternative word selected by the client from the list to refer to the symptoms (Table 3-1). TABLE 3-1 From Melzack R: The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods, Pain 1:277, 1975. Pain is an accepted part of the aging process, but we must be careful to take the reports of pain from older persons as serious and very real and not discount the symptoms as part of aging. Well over half of the older adults in the United States report chronic joint symptoms.17 We are likely to see pain more often as a key feature among older adults as our population continues to age. The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) reports the use of over-the-counter (OTC) analgesic medications for pain, aching, and discomfort is common in older adults along with routine use of prescription drugs. Many older adults have taken these medications for 6 months or more.18 Older adults may avoid giving an accurate assessment of their pain. Some may expect pain with aging or fear that talking about pain will lead to expensive tests or medications with unwanted side effects. Fear of losing one’s independence may lead others to underreport pain symptoms.19 Sensory and cognitive impairment in older, frail adults makes communication and pain assessment more difficult.18 The client may still be able to report pain levels reliably using the visual analogue scales in the early stages of dementia. Improving an older adult’s ability to report pain may be as simple as making sure the client has his or her glasses and hearing aid. The Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS) (Box 3-1) may be the most sensitive and reliable among older adults, including those with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment.20 But these and other pain scales rely on the client’s ability to understand the scale and communicate a response. As dementia progresses, these abilities are lost as well. A client with Alzheimer’s-type dementia loses short-term memory and cannot always identify the source of recent painful stimuli.21,22 The Alzheimer’s Discomfort Rating Scale may be more helpful for older adults who are unable to communicate their pain.23 The therapist records the frequency, intensity, and duration of the client’s discomfort based on the presence of noisy breathing, facial expressions, and overall body language. Another tool under investigation is the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. The PAINAD scale is a simple, valid, and reliable instrument for measurement of pain in noncommunicative clients developed by the same author as the Alzheimer’s Discomfort Rating Scale.24 A disadvantage of this pain scale is that the pain is inferred by the examiner or caregiver rather than self-reported directly by the individual experiencing the pain.25 Facial grimacing; nonverbal vocalization such as moans, sighs, or gasps; and verbal comments (e.g., ouch, stop) are the most frequent behaviors among cognitively impaired older adults during painful movement (Box 3-2). Bracing, holding onto furniture, or clutching the painful area are other behavioral indicators of pain. Alternately, the client may resist care by others or stay very still to guard against pain caused by movement.26 Untreated pain in an older adult with advanced dementia can lead to secondary problems such as sleep disturbances, weight loss, dehydration, and depression. Pain may be manifested as agitation and increased confusion.21 Older adults are more likely than younger adults to have what is referred to as atypical acute pain. For example, silent acute myocardial infarction (MI) occurs more often in the older adult than in the middle-aged to early senior adult. Likewise, the older adult is more likely to experience appendicitis without any abdominal or pelvic pain.27 Many infants and children are unable to report pain. Even so the therapist should not underestimate or prematurely conclude that a young client is unable to answer any questions about pain. Even some clients (both children and adults) with substantial cognitive impairment may be able to use pain-rating scales when explained carefully.28 The Faces Pain Scale (FACES or FPS) for children (see Fig. 3-6) was first presented in the 1980s.29 It has since been revised (FPS-R)30 and presented concurrently by other researchers with similar assessment measures.31 Most of the pilot work for the FPS was done informally with children from preschool through young school age. Researchers have used the FPS scale with adults, especially the elderly, and have had successful results. Advantages of the cartoon-type FPS scale are that it avoids gender, age, and racial biases.32 Research shows that use of the word “hurt” rather than pain is understood by children as young as 3 years old.33,34 Use of a word such as “owie” or “ouchie” by a child to describe pain is an acceptable substitute.32 Assessing pain intensity with the FPS scale is fast and easy. The child looks at the faces, the therapist or parent uses the simple words to describe the expression, and the corresponding number is used to record the score. A review of multiple other measures of self-report is also available,14 as well as a review of pain measures used in children by age, including neonates.35 In very young children and infants, the Child Facial Coding System (CFCS) and the Neonatal Facial Coding System (NFCS) can be used as behavioral measures of pain intensity.36,37 Facial actions and movements, such as brow bulge, eye squeeze, mouth position, and chin quiver, are coded and scored as pain responses. This tool has been revised and tested as valid and reliable for use postoperatively in children ages 0 to 18 months following major abdominal or thoracic surgery.38 Vital signs should be documented but not relied upon as the sole determinant of pain (or absence of pain) in infants or young children. The pediatric therapist may want to investigate other pain measures available for neonates and infants.39,40 The level or intensity of the pain is an extremely important but difficult component to assess in the overall pain profile. Psychologic factors may play a role in the different ratings of pain intensity measured between African Americans and Caucasians. African Americans tend to rate pain as more unpleasant and more intense than whites, possibly indicating a stronger link between emotions and pain behavior for African Americans compared with Caucasians.41 The same difference is observed between women and men.42,43 Likewise, pain intensity is reported as less when the affected individual has some means of social or emotional support.44 Assist the client with this evaluation by providing a rating scale. You may use one or more of these scales, depending on the clinical presentation of each client (see Fig. 3-6). Show the pain scale to your client. Ask the client to choose a number and/or a face that best describes his or her current pain level. You can use this scale to quantify symptoms other than pain such as stiffness, pressure, soreness, discomfort, cramping, aching, numbness, tingling, and so on. Always use the same scale for each follow-up assessment. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS)45,46 allows the client to choose a point along a 10-cm (100 mm) horizontal line (see Fig. 3-6). The left end represents “No pain” and the right end represents “Pain as bad as it could possibly be” or “Worst Possible Pain.” This same scale can be presented in a vertical orientation for the client who must remain supine and cannot sit up for the assessment. “No pain” is placed at the bottom, and “Worst pain” is put at the top. The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS; see Fig. 3-6) allows the client to rate the pain intensity on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). This is probably the most commonly used pain rating scale in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. It is a simple and valid method of measuring pain. An alternative method provides a scale of 1 to 5 with word descriptions for each number16 and asks: The 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey discussed in Chapter 2 includes an assessment of bodily pain along with a general measure of health-related quality of life. Nurses often use the PQRST mnemonic to help identify underlying pathology or pain (Box 3-3). After listening to the client describe all the characteristics of his or her pain or symptoms, the therapist may recognize a vascular, neurogenic, musculoskeletal (including spondylogenic), emotional, or visceral pattern (see Table 3-1). If the client appears to be unsure of the pattern of symptoms or has “avoided paying any attention” to this component of pain description, it may be useful to keep a record at home assisting the client to take note of the symptoms for 24 hours. A chart such as the McGill Home Recording Card16 (Fig. 3-7) may help the client outline the existing pattern of the pain and can be used later in the episode of care to assist the therapist in detecting any change in symptoms or function. There is also a Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire that has been validated for use to assess treatment response. It is designed to measure all kinds of pain—both neuropathic and nonneuropathic—using a numeric rating scale to assess 22 pain descriptors from zero (none) to 10 (worst possible).47 Because of the progressive nature of systemic involvement, the client may not have noticed any constitutional symptoms at the start of the physical therapy intervention that may now be present. Constitutional symptoms (see Box 1-3) affect the whole body and are characteristic of systemic disease or illness. A series of questions addressing aggravating and relieving factors must be included such as: The McGill Pain Questionnaire also provides a chart (Fig. 3-8) that may be useful in determining the presence of relieving or aggravating factors.

Pain Types and Viscerogenic Pain Patterns

Mechanisms of Referred Visceral Pain

Embryologic Development

Multisegmental Innervation

Direct Pressure and Shared Pathways

Assessment of Pain and Symptoms

Pain Assessment in the Older Adult

Pain Assessment in the Young Child

Intensity of Pain

Pattern of Pain

Aggravating and Relieving Factors

Pain Types and Viscerogenic Pain Patterns