Chapter 10

Pain management

Pain is a common complication of spinal cord injury which not only limits ability to perform motor tasks, but also has important implications for quality of life, well-being and general feelings of happiness.1–6 Physiotherapy is one component of a comprehensive pain management programme which typically involves pharmacological, surgical, psychological and behavioural interventions.

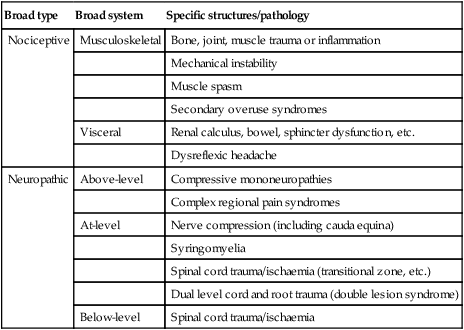

Pain associated with spinal cord injury can be categorized as either nociceptive or neuropathic (see Table 10.1).7,8 Neuropathic pain arises from primary lesions of the nervous system and the associated neural dysfunction, while nociceptive pain originates from musculoskeletal or visceral structures. Our understanding of the under-lying causes of neuropathic and nociceptive pain in patients with spinal cord injury is limited. There is some evidence to suggest that changes within the central nervous system following spinal cord injury lead to a heightened sensitivity (or neuronal excitability) and this contributes to the development of pain. Pain may have its origins at the receptor level or may be due to abnormal firing of neurons in the central nervous system either as a result of increased excitability through receptor changes or disruption of normal local and descending pain inhibitory pathways.6 However, most studies looking at prevalence and causative factors use cross-sectional rather than longitudinal designs, making even the identification of key prognostic factors problematic.6 The few more recent longitudinal studies have primarily looked at predictors of pain during the first 1–2 years after injury.4

Table 10.1

Classification of pain associated with spinal cord injury proposed by the Spinal Cord Injury Pain Task Force of the International Association of the Study of Pain8

| Broad type | Broad system | Specific structures/pathology |

| Nociceptive | Musculoskeletal | Bone, joint, muscle trauma or inflammation |

| Mechanical instability | ||

| Muscle spasm | ||

| Secondary overuse syndromes | ||

| Visceral | Renal calculus, bowel, sphincter dysfunction, etc. | |

| Dysreflexic headache | ||

| Neuropathic | Above-level | Compressive mononeuropathies |

| Complex regional pain syndromes | ||

| At-level | Nerve compression (including cauda equina) | |

| Syringomyelia | ||

| Spinal cord trauma/ischaemia (transitional zone, etc.) | ||

| Dual level cord and root trauma (double lesion syndrome) | ||

| Below-level | Spinal cord trauma/ischaemia |

Reproduced from Siddall P, Yezierski RP, Loeser JD: Pain following spinal cord injury: clinical features, prevalence, and taxonomy. Technical Corner Newsletter of the International Association for the Study of Pain 2000; 3:3–7, with permission of The International Association for the Study of Pain.

Assessment

The first and most important purpose of a pain assessment is to ensure that there is no reason for serious concern (e.g. fractures, infections, tumours, syringomyelia9).If in any doubt, patients should be assessed by a medical specialist. Symptoms which may indicate the need for further medical investigation include deterioration in motor, sensory, bladder or bowel function, recent loss of weight, deterioration in ‘balance’, raised temperature and night sweats. Aspects of the history which may suggest a more sinister underlying cause of pain include history of acute trauma, use of corticosteroids and history of cancer.10 It is also important to remember that patients with spinal cord injury are typically osteoporotic, and even minor physical injuries can cause fractures (see p. 21).

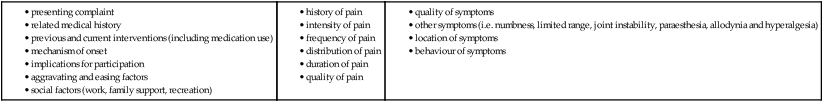

The assessment of pain relies on patient self-report about the characteristics of their pain, associated symptoms, activity limitations and participation restrictions (see Table 10.2).

Table 10.2

The assessment of pain includes patient’s self-report of the characteristics of their pain and associated symptoms

The common measures used to quantify pain intensity are the visual analogue scale11 and the numerical rating scale.12 Pain drawings can be used to identify the distribution of pain,13 and the McGill Pain Questionnaire14 can be used to assess the quality of the pain. There are also various questionnaire-based assessments for neuropathic pain.15 Other symptoms, such as reduced joint mobility, can be assessed using standard assessments of impairments (as outlined in previous chapters).

A pain assessment also needs to determine the implications of pain on activity limitations and participation restrictions. This is not only important for understanding the implications of pain on different aspects of patients’ lives, but also for establishing a baseline measure upon which change can be monitored. This is particularly important in patients with chronic pain. Often interventions do not change the characteristics of pain but rather change pain-related behaviours and coping mechanisms.16 These changes can be captured in measures of activity limitations and participation restrictions such as the Functional Independence Measure, Quadriplegic Index of Function, Spinal Cord Independence Measure or Barthell (see Chapter 2). An assessment specific to shoulder pain in patients with spinal cord injury is The Wheelchair User’s Shoulder Pain Index.17 This quantifies implications of shoulder pain on different aspects of patients’ mobility and life.

It is often also helpful for physiotherapists to consider the biopsychosocial dimension of pain, including the contribution of psychological, social and behavioural factors.18,19 Examples of measures which capture some of these dimensions of pain include the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire,20 the Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire,21 the SF-3622 and the Multidimensional Pain Inventory.15,23

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is difficult to treat, and is largely managed pharmacologically, although the small number of clinical trials in this area have generated conflicting results.6,24 There is some limited evidence to suggest that physiotherapy-type interventions designed to desensitize the affected dermatomes may be useful. TENS is also widely advocated, but currently without good evidence. Perhaps the largest role for physiotherapy, in patients with this type of pain, is encouraging graded exercise and activity to minimize secondary impairments and activity limitations. It is particularly important to ensure patients do not develop secondary contractures from holding limbs in protected positions (see Chapter 9).

Nociceptive pain

Nociceptive pain can be due to trauma, disease or inflammation of musculoskeletal or visceral structures. Physiotherapy interventions used to manage nociceptive pain include exercise, massage, stretch, re-education and guided return to activity.25 A recent Swedish study indicated that 63% of patients with spinal cord injury-related pain tried one or other of these types of pain-relieving interventions.25 Below is a summary of some of the more common musculoskeletal problems seen in patients with spinal cord injury (readers interested in pain from visceral origins are directed to Ref. 26).

Chronic back or neck pain

If back or neck pain persists for more than 3 months without any apparent underlying cause and develops into chronic pain, then it may be appropriate to use the existing clinical guidelines on the management of chronic neck and back pain advocated for the able-bodied population but modified in an appropriate way.27–31 These guidelines are based on high quality evidence and recommend minimal use of passive interventions, such as massage, electrotherapeutic agents or manual therapies, but rather appropriate, graded and supported return to active exercise and ‘normal’ activity, combined with reassurance about good prognosis. These guidelines do not recommend continued, ongoing and detailed physiotherapy-type assessments, unless there is reason to be concerned. They also highlight the futility of trying to make a precise diagnosis on the source of musculoskeletal pain and emphasize the importance of early efforts at minimizing fear, providing reassurance and encouraging graded return to activity.32 While these guidelines have not been systematically evaluated in patients with spinal cord injury, they would seem a reasonable starting point in the absence of more specific and relevant research. At least one clinical trial indicates the benefits of encouraging activity and exercise for relieving chronic pain in patients with spinal cord injury.33

Shoulder pain in patients with high levels of tetraplegia

Shoulder pain is common in patients with C5 and above tetraplegia. It is more common and intense in the first year after injury, with some estimating the incidence as high as 85%.34 In patients with established tetraplegia the incidence is between 45 and 60%.35–37

Possible causes

There are many different theories about the possible causes of shoulder pain in patients with tetraplegia (and stroke) including subluxation, poor physical handling by carers, prolonged sitting and lying, and limited change of shoulder position. Typically, small studies look at the relationship between shoulder pain and some of these factors.34,38,39 However, a theoretical argument about the importance of each factor can be mounted and, without large-scale prognostic studies, it is not known which of these factors is most important and where therapeutic attention is best directed.

Subluxation

Shoulder pain may be due to overstretching of the delicate soft tissues around the glenohumeral joint secondary to inferior subluxation. Any tendency for subluxation may be increased by downward and medial rotation of the bottom tip of the scapula. In turn, medial rotation of the scapula may be precipitated by paralysis of the serratus anterior muscles and loss of extensibility in the rhomboid muscles. Dropping of the inferior lip of the glenoid fossa diminishes the scapula’s ability to support and protect the head of the humerus against distracting forces. The tendency for inferior subluxation may be further aggravated through poor physical handling from therapists and carers. These and other theories about the relationship between shoulder subluxation and pain have been widely discussed since 1957,40 but they are still speculative and contentious.41–43

Recent attention has been directed at determining the most effective way to treat and prevent shoulder subluxation, although most of the clinical trials in this area have been with patients following stroke, not spinal cord injury.42,44 Some studies indicate that shoulder support reduces subluxation45 but does not decrease pain, while others show a treatment effect on pain but not subluxation.42 A recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that, in patients with stroke, there is insufficient evidence to indicate whether supportive devices prevent subluxation, although they may delay the onset of shoulder pain.46 Regardless, therapists are well advised to ensure that the arm troughs of wheelchairs are appropriately adjusted to provide shoulder support. Shoulder support can also be provided with pillows, strapping, lap boards, slings or shoulder harnesses (see Figure 10.1).42,45,47

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree