CHAPTER 40 Paget’s Disease

INTRODUCTION

Osteitis deformans was initially described by Sir James Paget, an English surgeon, in 1877 as a chronic inflammation of bones.1 Paget’s disease is the second most common metabolic bone disease after osteoporosis, and frequently involves the spine. It is uncommon prior to middle age. In its milder form it can be quite common, with 2–4% of individuals older than 55 showing evidence of the disease. It is characterized by a slowly progressive deformation and enlargement of bone. This chapter will review pertinent information about this disorder that is relevant to spine care.

ETIOLOGY

An infectious cause of this disorder has some support through ultrastructural, immunologic, and molecular studies. Specifically, osteoclasts in patients with Paget’s disease have microfilaments in the nucleus and cytoplasm that are similar to the nucleocapsids of viruses of the paramyxovirus family. The paramyxovirus family includes the measles virus, canine distemper virus, and the respiratory syncytial virus.2 In a study of 53 English patients with known Paget’s disease the presence of measles virus of the paramyxovirus family was examined.3 Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed on bone biopsy specimens, bone marrow, or peripheral blood mononuclear cells looking for evidence of paramyxovirus RNA. Other subsequent evaluation of the tissue was also performed. No evidence of paramyxovirus was found. None of the proposed viral causes of this disorder has shown consistent results.

In up to 40% of patients there is a familial connection.4 A genetic cause that is autosomal dominant has been described within families particularly affected with the disorder.5–7 A genetic cause for the common form of the disorder has not been found. In a similar rare disorder, familial expansile osteolysis, a mutation on chromosome 18 associated with receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK).8 No RANK mutations have been found in Paget’s disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The epidemiology of Paget’s disease of bone is difficult to study, as most individuals are diagnosed with Paget’s disease in an asymptomatic state through routine testing for other problems. It is found routinely in the United States, Australia, England, New Zealand, Canada, and France. A Mayo Clinic retrospective chart review study to determine some of the characteristics of patients with this disease was performed.9 Patients with the diagnosis of Paget’s disease diagnosed for the first time between 1950 to 1994 from Olmsted County, MN, were identified. Demographic information about this population was presented. The mean age of patients with this diagnosis was 69.6 years with a statistically greater number of men (n=129) than women (n=107) being diagnosed with the disease. The diagnosis of Paget’s disease became less frequent during the study period and the authors suggested that this may be due to changes in the routine chemistry panel early in the study producing an increase in incidence.

To estimate the prevalence of Paget’s disease in the United States a secondary review of pelvis films obtained during the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-I) was performed.10 The NHANES-I study sampled a representative population of citizens and included, among other information, radiographs. Of this sample all men between the ages of 25 and 74 and women from 50 to 74 had pelvic radiographs. Of the 4897 radiographs of the pelvis 3936 were available for review. The radiographic criteria for Paget’s disease used in the study included the following: expansion of bone size, thickened disorganized trabeculae, thickened expanded cortex, osteosclerosis, and deformity. Pelvic Paget’s disease prevalence was estimated as 0.71%±0.18%. No racial difference was observed in this sample. Factors associated with the presence of disease were older people with a slightly higher male predominance and distribution in the northeast United States.

Geographic variation in Paget’s disease has also been observed in the United Kingdom in a study performed through 1974 involving 14 towns.11 The overall prevalence rate was 5.4% for people older than 55 years. Within this study a focus of increased prevalence in three towns clustered in Lancashire was observed, with a prevalence of 8.3%. This was compared to a prevalence of 2.3% in Aberdeen, Scotland. This increased prevalence in Lancashire was confirmed in a follow-up in 1980 and has suggested the possibility of an environmental or infectious factor but this could not be confirmed.12 No other area in Europe had demonstrated as high a prevalence rate as the United Kingdom for this time period.

Cooper et al.13 performed an interesting subsequent study with the same design and 10 of the original towns as performed in 1974 study by Barker et al. The goal was to determine if there had been a change in the prevalence since the original study. A record review was performed for the period 1993–1995. Any patient over 55 years of age with a pelvis, lumbar spine, sacrum and femoral head film was included in the study. The films were reviewed by two radiologists including a consultant radiologist who participated in the original 1974 study. For this period of time they were able to identify 9828 individuals (4625 men, 5203 women). The overall prevalence rate was 2%, with a male:female ratio of 1.6:1. As observed previously, there was an increase in prevalence with an increase in age. The prevalence in the 10 towns studied was 40% less than that observed in the initial study performed in 1974. This reduction in prevalence was greatest in the towns with the highest rates in the initial study.

During an archeological survey of 2770 skeletons in the United Kingdom for Paget’s disease a prevalence of 2.1% was observed.14 The prevalence prior to AD 1500 was 1.7% and after this time increased to 3.1%. This difference was possibly due to the small sample size. The distribution of involvement was the same as within modern studies.

In a French study, 770 patients were randomly selected from 7598 women being studied for fracture risk.15 The anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the spine were reviewed by two rheumatologists and classified into categories with or without Paget’s disease. These radiographs were subsequently read by two masked reviewers for the presence of Paget’s disease. Spinal Paget’s disease was present in 0.54%, which provides an overall prevalence of disease in the 1.1–1.8% range.

Paget’s disease is a less frequent diagnosis in Asian countries with most descriptions being case reports.16 The reason for this reduced frequency in Asian countries, like the etiology of Paget’s disease itself, remains unclear.

Anatomic distribution

Paget’s disease affects one bone in 5% of patients with the average number of areas involved averaging 6.5 per patient.17 Cranial enlargement can be associated with change in hat size or prominence of superficial scalp veins. In a study designed to examine the anatomic distribution of Paget’s disease in patients older than 55 with films of the lumbar spine, pelvis, and proximal femur within the UK, the stored films of radiology practices of 31 different centers were examined.18,19 The diagnosis of Paget’s disease was made on radiographic criteria and further films examined for 1864 patients. Pelvic involvement was observed in 76% of patients. The lumbar spine was next in frequency with 34%, followed by the femur in 32%, shoulder 24%, thoracic spine 22%, sacrum 14%, skull in 12%, and cervical spine in 5%.

Quality of life issues were addressed in a questionnaire mail survey of 958 patients with Paget’s disease. The most commonly affected areas within the sample were skull (34%), spine (35%), pelvis (49%), and leg (48%).20 Hearing loss was reported by 37% of patients. Problems of deformity associated with Paget’s disease were also a frequent complaint with bowed legs (31%), enlarged heads (17%), leg length discrepancies (25%). Of concern was that 47% reported depression associated with the disorder and this was found to have a greater impact on quality of life than the biomedical or self-care domains.

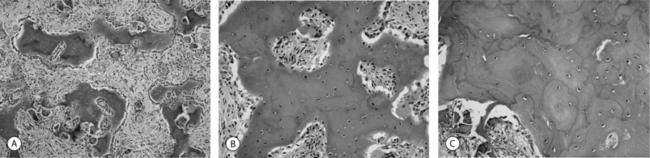

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Paget’s disease involves accelerated bone turnover and remodeling (Fig. 40.1) There is simultaneous excessive osteoclastic resorption and osteoblastic deposition. The involved bone is extremely vascular and may exhibit arteriovenous shunts. The initial active phase is predominantly osteolytic, creating weakened, deformed bone. Following this phase is an osteosclerotic phase which is primarily osteoblastic, resulting in deposition of bone and enlargement of the long bones with thick dense bone without the normal lamellar pattern. The resulting pattern is an irregular mosaic pattern of mature and immature bone. This creates the potential for fractures as well as the deformities observed in the long bones due to deposition.

PRESENTATION AND COMPLICATIONS

Low back pain and osteoarthritis

Low back pain is a complaint of approximately a third of patients with Paget’s disease.21 As in other areas of spine care, it is difficult to separate other potential causes of spinal pain from Paget’s disease.

It has been suggested that the presence of osteoarthritis is greater in patients with Paget’s disease.22 Paget’s disease as a causative factor due to altered mechanics around the joint has been proposed a potential reason for this observation.

A matched-control radiographic comparison study was performed to resolve the question if a greater occurrence of osteoarthritis exists in patients with Paget’s disease.23 Using 100 patients with Paget’s disease of the spine and a matched sample without disease, no difference in prevalence was observed.

In a similar radiographic study to determine the prevalence of articular osteoarthritis associated with Paget’s disease 153 matched pairs of patients with and without Paget’s disease was selected. At the time of comparison 87 matched pairs with 248 films were available for review and there was no difference in articular osteoarthritis between the groups.24

In a well-designed descriptive study Hadjipavlou and Lander found 54% of patients complained of low back pain.25 It was felt that within this group of patients the symptoms could be attributed to a specific cause based on radiologic causes. In the majority of patients, 50%, complaints of low back were felt to be due to degenerative disease. In the remaining patients, the complaint was related in 26% to a combination of Paget’s disease and osteoarthritis, and in 24% of these patients the complaint of low back pain was attributed solely to Paget’s disease.

In a retrospective study of 245 patients with complete spinal radiographs 14 were found to have Paget’s vertebral ankylosis (PVA).26 The presence of diffuse interstitial hyperostosis (DISH) within this study population was 80 out of 245. Out of the 11 patients with PVA, 8 had findings consistent with DISH. The authors suggest that the presence of DISH may allow Paget’s disease to spread to adjacent vertebrae. A separate study to determine if DISH is more prevalent in patients with Paget’s disease was performed. In a group of 50 patients with Paget’s disease compared to 50 age- and sex-matched controls a statistically significant higher prevalence of DISH was observed, 24% compared to 6% in the control group.27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree