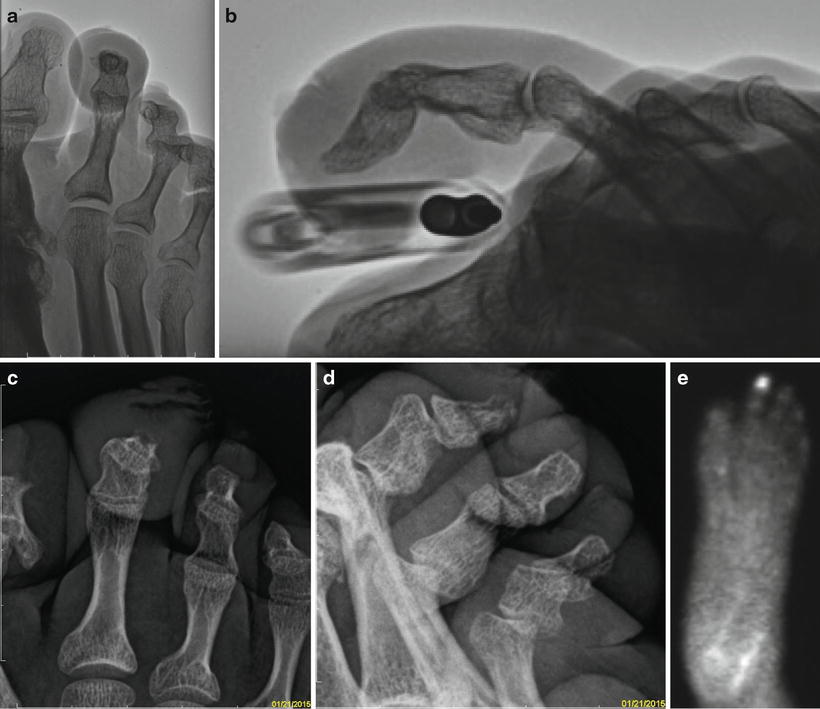

Fig. 16.1

Osteomyelitis of a central toe is typically associated with direct spread of infection from neuropathic ulcers and digital gangrene. Neuropathic ulceration at the tip of the third toe with contiguous spread of infection to the deep tissues resulted in cellulitis and osteomyelitis (a, b). Note how the infected wound probed deep to bone which raised suspicion for osteomyelitis at the tip of the distal phalanx (c). Neuropathic ulceration over prominent interphalangeal joints also leads to bone and joint infection (d). Osteomyelitis associated with digital gangrene is usually a late stage finding that develops secondary to infection of the surrounding tissue (e)

Biomechanical Considerations in Neuropathic Ulceration

Digital deformities and abnormal biomechanical issues associated with central toe ulceration include hammertoe contracture, transverse plane toe deformity, hallux valgus, hallux limitus, overlapping toes, bone spurs, arthritis, excessive toe length, and ankle equinus. Deformity alone is typically not sufficient to cause ulceration, whereas the dyad of neuropathy and deformity is almost always present. Hammertoe deformity predisposes to abnormal pressure on the dorsal aspect of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) or distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) as well as the distal tip of the toe near the toenail (Fig. 16.2). Dorsal ulceration is amenable to extra-depth toe box shoe therapy, while the tip of toe ulceration associated with hammertoe contracture is less easily rectified with simple shoe or insert measures. Patients with neuropathic wounds oftentimes present with chronic wounds that already have deep-seated osteomyelitis at which point conservative measures are no longer a viable option. Hammertoe contracture also creates a retrograde buckling force on the metatarsal head, which results in abnormal pressure on the plantar aspect of the metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ). Interdigital ulceration is associated with transverse plane deformity (medial or lateral drift), hallux valgus, and overlapping toes. Arthritic interphalangeal joints (IPJs) can also become enlarged and prominent with resultant soft tissue breakdown which may ultimately lead to osteomyelitis. Isolated elongation of a central toe (commonly the second) is associated with nonhealing and recurrent tip of toe ulceration which is highly prone to osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx. An uncomplicated wound on a long toe can be rectified with proper fitting shoes, but the longest toe is commonly contracted at the tip which exacerbates the problem.

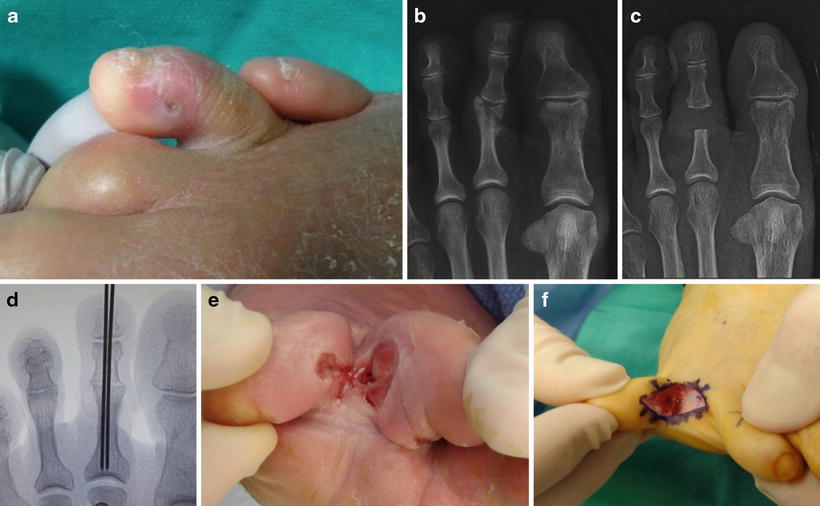

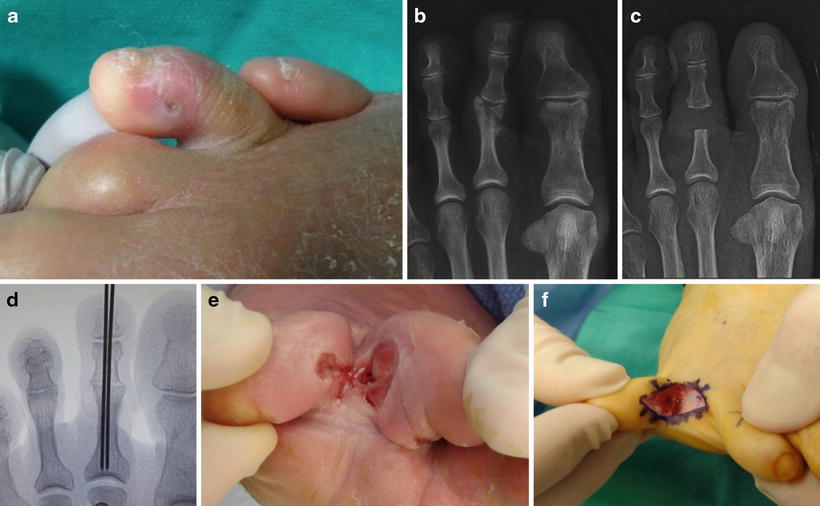

Fig. 16.2

Digital deformity predisposes to nonhealing neuropathic wounds. Neuropathic ulcers associated with digital deformity tend to be chronic and recurrent. Nonhealing sores may eventually become infected, and osteomyelitis is common in digital wounds. Long and contracted hammertoes commonly develop neuropathic ulcers at the tip of the toe (a, b). Note the classic appearance of neuropathic ulceration with callused border and healthy granulation tissue at the center of the wound. Cellulitis around the tip of the toe (a) with a deep wound (b) should raise suspicion for osteomyelitis in the distal phalanx. Excessive toe length is often created by adjacent toe amputation (c). Dorsal ulceration at the IPJs is associated with hammertoe contracture (d) and overlapping toes (e)

Wound Care Challenges for Central Toe Ulceration

Conservative therapy of digital ulcerations typically focuses on reducing pressure and off-loading the problematic area, as well as appropriate local wound care. Offloading is often in the form of orthotic inserts, shoes with an extra-depth toe box to allow room for the contracted toe (s), or digital pads to protect against dorsal, plantar, or interdigital pressure. These measures are especially useful for pre-ulcerative or superficial ulcerative lesions. If these conservative measures fail to aid in timely wound healing, osteomyelitis is a frequent sequelae.

Conservative off-loading measures may not be effective if the wound is caused by digital deformity more so than ill-fitting shoes. Tip of toe ulceration associated with mallet toe deformity does not respond to longer shoes, and interdigital wounds may not resolve with wider shoes if the problem is caused by hallux valgus or an overlapping second toe. Understanding the biomechanics of neuropathic forefoot ulceration is therefore important and has significant impact when deciding on the ideal treatment plan including surgical procedure selection.

Prophylactic Surgery for Correction of Digital Deformity

Osteomyelitis of a central toe is most commonly associated with a chronic wound that has failed to heal. Early surgical intervention allows prophylactic treatment of recurrent or nonhealing ulcerations with the intent to avoid progression to contiguous spread osteomyelitis and/or acute infection requiring amputation. The central toes are very amenable to reconstructive podiatric procedures which are designed to correct structural deformity and reduce bone prominence yet maintain a functional or at least cosmetically appealing toe.

Flexor and Extensor Tenotomy for digital Ulcers Associated with Flexible Hammertoe Deformity

Distal tip of toe ulceration and dorsal ulceration at the IPJs is commonly related to flexor and extensor tendon contracture, which is accentuated during ambulation. Deformity becomes rigid with time but often remains flexible for years. Flexor tenotomy has been documented as a reliable procedure to treat tip of toe ulcerations if performed early enough in the life cycle of an ulcer before deeper structures become infected [1]. Isolated flexor tenotomy is reserved for distal tip of toe ulcerations, while dorsal PIPJ ulcerations may require both flexor and extensor tenotomy. In our practice, digital tenotomy is typically performed in the office under local anesthesia and sterile conditions (Fig. 16.3). Care must be taken to thoroughly evaluate the contracted toe preoperatively, as tenotomy may lengthen an already elongated toe resulting in increased pressure if not accommodated by longer shoes. Tip of toe ulcers associated with an elongated and contracted toe, a severely diseased toenail, and deep ulceration with potential for osteomyelitis are best treated with distal Symes amputation (discussed later in this chapter). Rigid joint contracture is typically not amendable to tenotomy and may respond better to IPJ arthroplasty.

Fig. 16.3

Clinical examples of flexor tenotomy for tip of central toe ulcers associated with flexible hammertoe contracture. Digital contracture is highly correlated with tip of toe ulceration. This second toe wound was recurrent due to hammertoe contracture (a). Early intervention with flexor tenotomy before worsening ulceration turns to infection, and osteomyelitis is ideal under these conditions. Flexor tenotomy can be performed on one or all of the lesser toes depending on clinical findings. Note abnormal pressure on the tips of toes 2–5 with site marking for office-based tenotomy (b). Minimally invasive flexor tenotomy with plantar PIPJ capsulotomy was performed using a #62 blade through plantar midline incisions (c). Advanced DJD of the PIPJ or more complex toe deformities are be better treated with joint arthroplasty or fusion. Dorsal MPJ tenotomy and capsulotomy is common as well. Note improved toe position 1 week after tenotomy (d). Minimally invasive surgery allowed normal activity in a compressive bandage and surgical shoe. No sutures were needed for this transverse incision, and normal shoes and bathing are allowed 1 week after surgery. Note a fully healed transverse incision 1 week after office-based flexor tenotomy without suture on the second toe (e). The same procedure was performed on the third, fourth, and fifth toes 2 years prior

Elective Hammertoe Surgery for Digital Ulceration

Interdigital wounds and wounds over the dorsal aspect of an IPJ are due to prominent underlying bone structures caused by prominent joints, arthritic spurs, transverse plane digital deformity, overlapping toes, and malunion of prior digital fracture (Fig. 16.4). Hallux valgus deformity also contributes to increased interdigital pressure from abutting toes. Conservative treatment, such as wound debridement, wide shoes, toe spacers, and lamb’s wool, may allow healing or prevent interdigital calluses from turning into formal ulcerations. Of note, wider shoes may not solve the problem if hallux valgus is the underlying cause of interdigital pressure (Fig. 16.5). Consideration should be given to addressing digital deformity or boney prominence when there is propensity to develop wounds around the IPJs, especially in high-risk diabetic patients. Timeliness is important as this preventive approach may allow a minor outpatient or office-based procedure before a pre-ulcerative lesion or recurrent sore becomes deep and infected.

Fig. 16.4

Osteomyelitis associated with interdigital ulceration. Interdigital ulcers (a) commonly start as soft corns that eventually develop deep sinus tracts near prominent bone and joint structures. Note a malunited fracture at the second PIPJ with propensity for interphalangeal pressure on the adjacent toes (b). Bone spur resection or IPJ arthroplasty may be the most prudent prophylactic intervention for persistent sores that have failed to heal despite proper offloading and wide shoes. Arthroplasty of the PIPJ removed the prominent underlying bone and provided specimen for biopsy (b, c). Arthrodesis is less desirable with infection but is an option for uncomplicated sores (d). Consideration is given to arthroplasty with partial syndactylization for adjacent interdigital ulceration with poor quality tissue in the interdigital space (e, f)

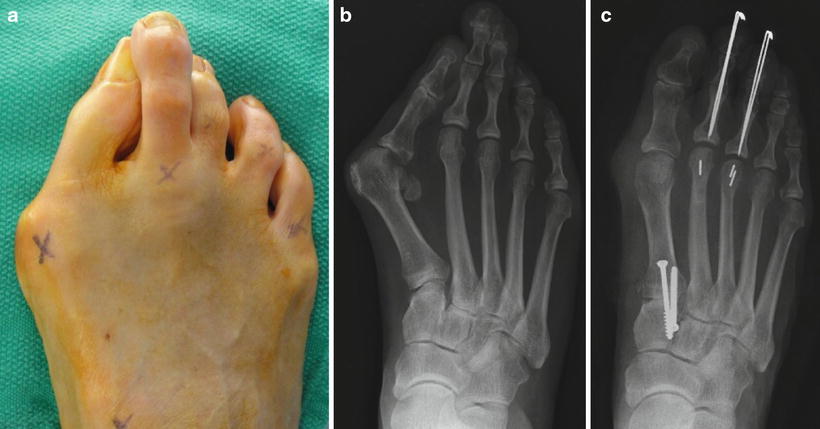

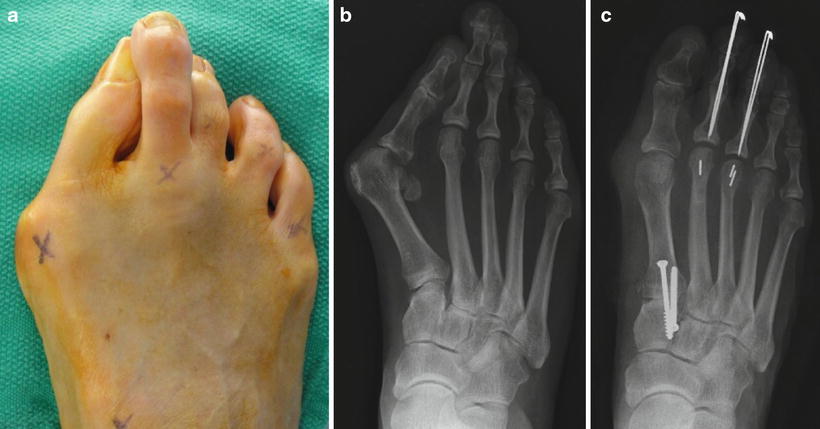

Fig. 16.5

Interdigital ulceration associated with an overlapping second toe and hallux valgus deformity. Hallux valgus deformity complicates matters with regard to ideal procedure selection for interdigital second toe ulceration (a, b). Second digital amputation may be the most prudent approach once a deep wound becomes complicated with cellulitis and osteomyelitis. Elective reconstructive procedures including bunionectomy, first MPJ or midfoot fusion, and hammertoe repair are more feasible if surgery is performed before the onset of infection (c)

PIPJ and DIPJ arthroplasty traditionally involves removal of the distal portion of the proximal or middle phalanx, respectively. Periarticular exostectomy with preservation of the joint is also common for interdigital wounds. Bone resection allows removal of prominent bone, relaxation of deformed joints, bone specimen for biopsy, and possible wound excision and closure. A dorsal incisional approach is typical regardless of wound location as interdigital incisions are challenging. An elliptical dorsal incision allows dorsal wound excision and primary closure, whereas interdigital wounds may be left to heal secondarily. The surgeon can also attempt to heal the ulcer preoperatively with offloading and local wound care followed by traditional hammertoe or bunion surgery once the ulcer is completely healed.

Osteomyelitis Associated with Digital Gangrene

Phalangeal osteomyelitis associated with gangrene typically develops late in the course of digital gangrene. Noninfected dry gangrene of the lesser toes is primarily treated with vascular intervention, while the affected toe is initially left alone to allow demarcation. Dry gangrene can be monitored for months while waiting to see if autoamputation is likely to occur. This process can be successful depending on restoration of digital perfusion and extent of tissue necrosis. Autoamputation ideally occurs distal to the tip of the distal phalanx which allows natural healing. Autoamputation through the IPJs results in bone and cartilage exposure which is less amenable to secondary healing. Some patients are able to granulate over the end of the bone, but osteomyelitis may eventually develop if bone remains exposed for an extended period of time. Conversion to a clean surgical site is often preferred and may simply require cutting the bone short enough that the soft tissue can finally heal over the bone.

Dry gangrene may eventually turn to infected wet gangrene as the nonviable tissue becomes necrotic and infected. Infected gangrene is commonly associated with osteomyelitis since full-thickness necrosis includes necrosis of the periosteum and joint capsule. The wait and watch approach is no longer an option once infection develops and surgical treatment is typically necessary. A surgical cure of phalangeal osteomyelitis associated with gangrene is likely to be achieved with toe, ray, or transmetatarsal amputation (TMA), but healing may be compromised in comparison to patients undergoing amputation for neuropathic conditions.

Central digital gangrene can also occur due to an embolic event which is less likely to become infected or need amputation. Embolic lesions tend to be smaller and may impact multiple toes which should prompt work up to identify a cause. These lesions are more amenable to the wait and watch approach to allow demarcation and eventual healing.

Diagnosis of Central Digital Osteomyelitis

The diagnosis of central digital osteomyelitis requires consideration of the entire clinical picture since standard X-rays have a poor diagnostic track record. Advanced imaging is less practical for the small phalangeal bones of the central toes. Special X-ray techniques are helpful to isolate the area of concern since imaging of the involved toe may be compromised by overshadowing from adjacent toes and digital contracture (Fig. 16.6). The probe-to-bone test is particularly useful with toe ulcerations since bone is fairly close to the skin surface, though the positive predictive valve has been controversial [2, 3]. A nonhealing digital wound with deep depth or sinus tract concerning for bone or joint exposure plus clinical evidence of soft tissue infection should raise suspicion for osteomyelitis. Plain radiographs and laboratory workup combined with clinical findings are the mainstay of diagnosis at this stage, and we rarely pursue advanced imaging for central toe wounds. Bone biopsy is the next logical step which can be obtained in the process of bone debridement, IPJ arthroplasty, tip of toe amputation, or removal of the entire toe. The decision to remove the entire toe has more to do with compromised soft tissue or severe deformity that is not amenable to reconstructive procedures which are determined by clinical exam rather than MRI or bone scan. Needle biopsy of a central toe is possible but can be challenging due to the small nature of the phalanges and close proximity of wounds to the IPJs, toenail, and vascular structures. Needle biopsy does not address digital deformity or bone prominence, and therefore open bone resection may be the most prudent method to obtain bone specimen for biopsy.

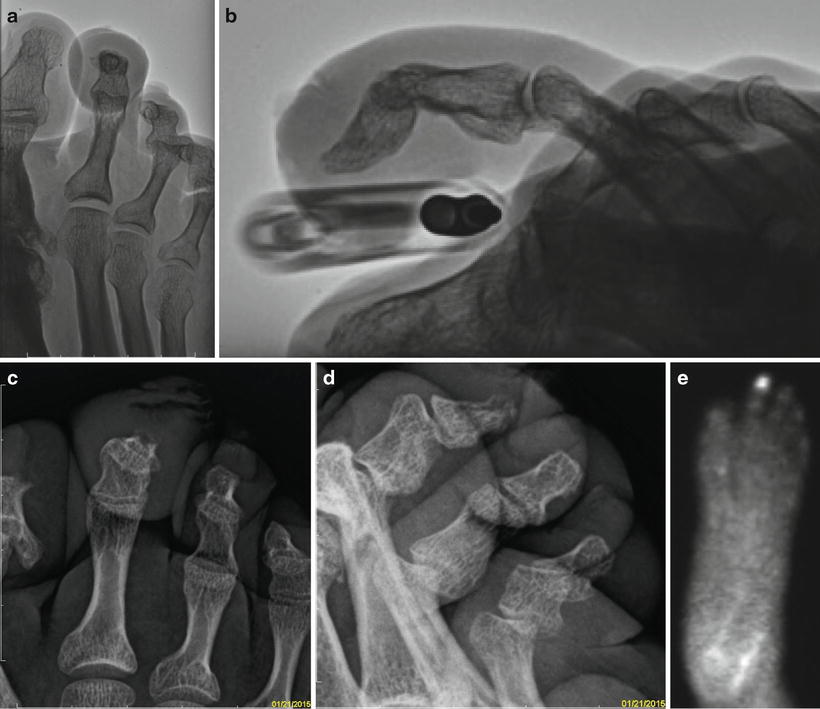

Fig. 16.6

Imaging for central toe osteomyelitis. Cortical erosion near the site of ulceration is the most common finding in osteomyelitis associated with contiguous spread of infection. Radiographic signs of osteomyelitis are not immediately visible on standard X-rays, but baseline imaging is useful to evaluate for underlying structural deformity. Other conditions may be identified on standard X-ray including arthritis, malunited fractures, and gouty arthropathy. Contracture of the distal phalanx (a) created imaging challenges for the tip of second toe ulcer shown in Fig. 16.2b. A raised toe view helped to isolate the tip of the distal phalanx on this lateral view (b). Osteomyelitis was found on biopsy despite normal X-ray findings. A different patient with erosion of the second distal phalanx correlated with location of ulceration at the tip of the toe (c, d). Comparison to the adjacent third toe distal phalanx helps to pick up early loss of cortex since the tip of the distal phalanx has a naturally occurring irregular cortical margin. Bone scan is not part of our routine work up for lesser toe infection but may be useful in certain circumstances (e). Note how uptake is localized to the tip of the second toe

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree