CHAPTER 6 Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

Sport-specific injuries more frequently affect young athletes with earlier and more rigorous participation in sports. The radiocapitellar compartment of the young athlete’s elbow is punished by significant stresses during repetitive throwing or during sports (e.g., gymnastics) that convert the elbow joint into a weight-bearing joint.1 Lateral compartment compression can lead to Panner’s disease (i.e., osteochondrosis) in the 6- to 10-year old patient or to various stages of capitellar osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) in the adolescent or young adult.2–5 This chapter describes Panner’s disease and OCD and outlines a treatment algorithm, including arthroscopic management using osteochondral grafting.

PANNER’S DISEASE

In 1927, Hans Jessen Panner published a description of osteochondrosis of the capitellum, likening it to Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease of the hip.6 Like other ostochondroses, it consists of non-inflammatory, disordered endochondral ossification. Its specific cause and relation to OCD remain debatable. It is known that abnormal radiocapitellar compressive forces during a period of vulnerability, typically while the physes are still open, predispose children to Panner’s disease.2,5,7 It may result from the combination of an avascular insult (likely related to the capitellum’s predominantly end-artery supply) and repetitive microtrauma.8

Epidemiology

Panner’s disease predominantly affects boys younger than age 10 years.9 Young boys may be predisposed to it for two reasons. First, compared with girls, they have a delayed appearance and maturation of their secondary growth centers. Second, boys traditionally are more prone to trauma during the more aggressive early childhood activities they select.7 This may change as more girls choose higher-risk athletic activities at younger ages. Although Panner’s disease can be confused with OCD, and the age of onset may overlap, it is distinguished by three epidemiologic characteristics. Panner’s disease does not share the strict association with repetitive throwing that OCD does, it is usually self-limited, and it resolves without any long-term sequelae.

Patient Evaluation

Panner’s disease initially manifests as pain and stiffness in the elbow, which is relieved by rest. On physical examination, patients have poorly localized tenderness over the lateral elbow. Radiographs initially show fissuring, lucencies, fragmentation, and irregularity of the capitellum (Fig. 6-1), particularly near or at the chondral surface. Subsequent x-ray films, taken at 3 to 5 months, demonstrate larger radiolucent areas followed by reossification of the bony epiphysis, with a corresponding resolution of symptoms. In 1 to 2 years, the epiphysis regains its contour, usually without flattening.4 As in Legg-Calvé-Perthes, radiographs often lag behind clinical symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used effectively to document the extent of the lesion. Typically, edema is localized to the chondral surface and the bone adjacent to it, with less involvement of the deeper subchondral bone compared with the OCD (Fig. 6-2).

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS

OCD of the capitellum is a non-inflammatory degeneration of subchondral bone occurring in the context of repetitive trauma to the lateral compartment of the elbow. Panner’s disease and OCD may represent two different stages of the same disorder,4 but they do have different characteristics: age of onset, cause, and natural history. Although Panner’s disease affects children younger than 10 years, OCD victimizes older athletes, usually between the ages of 11 and 15 years.10 Unlike Panner’s disease, OCD is thought to be directly linked to repetitive trauma. OCD is not always a self-limited disease, and if left unaddressed, it results in profound destruction of the capitellum.10

Anatomy

The elbow’s osseous anatomy and the capitellum’s idiosyncratic blood supply may predispose young athletes to OCD. The elbow is a diarthrodial joint in which the distal humerus articulates with the proximal ulna and the radial head. Its unique bony configuration allows for −15 to 0 degrees° of extension to 150 degrees of flexion. Rotation of the radial head over the stationary ulna gives an arc of almost 180 degrees of forearm rotation.11 The osseous and articular congruency of the humerus, ulna, and radial head accounts for the greater part of elbow stability, particularly at less than 20 degrees of extension or more than 120 degrees of elbow flexion.12

In young, skeletally immature athletes, the elbow possesses a greater degree of cartilaginous elasticity. Hyperextension, facilitated by this increased range of motion, can generate increased radiocapitellar compressive loads and tension of the medial capsule and ulnar collateral ligament (UCL). Overhead throwing athletes during the throwing motion and gymnasts during weight-bearing handstands in elbow hyperextension further exaggerate these stresses. Repetitive stress on this system can precipitate OCD. Medial-sided pathologies, such as medial apophysitis, UCL injury, and posteromedial impingement from the excess valgus stress, can occur concurrently.13

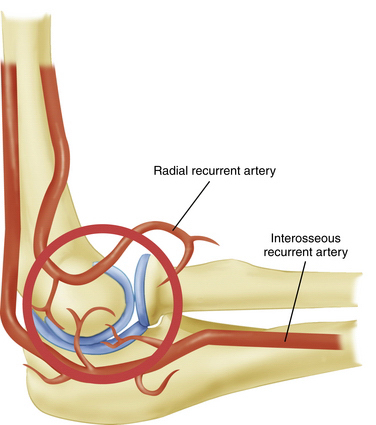

The tenuous end-artery vascular supply to the capitellum predisposes it to injury. In the young adult population, the capitellum is supplied by two end arteries coursing from posterior to anterior, which are branches of the radial recurrent and interosseous recurrent arteries (Fig. 6-3).14 As a result of the longitudinal blood supply to the capitellar epiphyseal plate and minimal collateral circulation in the area, blood flow to the capitellum may be disrupted by repetitive microtrauma resulting in an avascular state and by a single traumatic event leading to post-traumatic subchondral bone bruises.15,16

Patient Evaluation

History

OCD arises from repetitive, excessive compressive forces generated by large valgus stresses on the elbow during throwing or racket swinging or by constant axial compressive loads on the elbow, such as those endured by gymnasts.10,17,18 Specific risk factors predispose to the condition. In the case of baseball players, throwing sliders and breaking pitches, throwing more than 600 pitches per season, and increased age of the athlete increase the risk of developing OCD.18 In female gymnasts, overtraining involving excessive handstand maneuvers has been linked to OCD.19,20 There also may be a genetic predisposition to OCD.

Patients with OCD initially complain of pain and stiffness in the elbow that is relieved by rest. The onset is usually insidious, and a history of specific trauma is often absent. If left unaddressed, the symptoms may progress to locking or catching due to intra-articular loose bodies or an inflamed plica. Throwing athletes may present with painful posterolateral clicking or catching caused by a radiocapitellar plica. These symptoms can overlap with those from the OCD lesion, and the plica itself may be responsible for chondral wear in the radiocapitellar compartment.

Physical Examination

In athletes with OCD, physical examination findings tend to be remarkable for poorly localized lateral elbow tenderness over the radiocapitellar joint. Loss of range of motion with a 15- to 20-degree flexion contracture is common. Loss of extension is more common than loss of flexion. An effusion is often apparent and can be palpated by flexing the elbow and feeling the lateral portal area, triangulated by the radial head, olecranon, and lateral epicondyle. The provocative maneuver for the radiocapitellar joint we prefer is the active radiocapitellar compression test (Fig. 6-4). A positive test result elicits pain in the lateral compartment of the elbow when the patient pronates and supinates the forearm with the arm in extension. In patients with an associated symptomatic radiocapitellar plica, snapping typically occurs at greater than 90 degrees of elbow flexion with the forearm in pronation.

Diagnostic Imaging

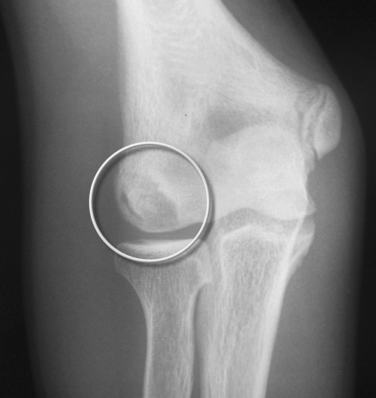

Anteroposterior radiographs in full extension, anteroposterior radiographs in 45 degrees of flexion, and lateral views of the elbow should be obtained. Radiographic findings may be negative early in the disease process. As the condition progresses, flattening and sclerosis of the capitellum, typically on its anterolateral aspect, will become apparent. Irregular areas of lucency and intra-articular loose bodies also appear. The capitellar lesions of OCD and medial-sided epicondylar fragmentation are best seen on an anteroposterior radiograph at 45 degrees of elbow flexion (Fig. 6-5).

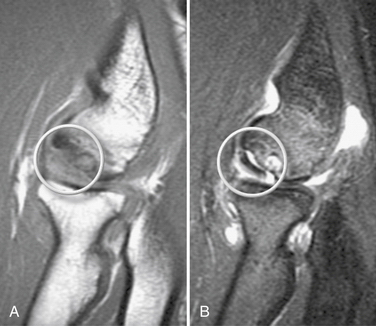

MRI should be used to assess suspected OCD. It can detect bone edema early in the disease process.21 An MR arthrogram can further delineate the extent of the injury. Contrast can show separation of a detached or partially detached piece from subchondral bone (Fig. 6-6). This is important in determining whether to proceed with operative or nonoperative management. Peiss and colleagues22 thought that fragment enhancement (Fig. 6-7B) (as opposed to the perifragment enhancement seen in Fig. 6-6) denoted viability and might be a reasonable indication for nonoperative treatment. They also suggested that enhancement of the fragment and subchondral bone interface was caused by vascular granulation tissue, indicating instability and requiring operative intervention.

FIGURE 6-6 The MR arthrogram shows contrast surrounding an unstable osteochondritis dissecans fragment (arrow).

(Courtesy of Neal S. ElAttrache, MD, Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic, Los Angeles, CA.)

Pseudolesions, which appear on the posteroinferior junction of the articular and nonarticular portions of the capitellum, must be differentiated from OCD, which almost always manifests on the anterolateral aspect. The examiner also should observe whether the capitellar physis is open or closed.

Treatment

Indications, Contraindications, and Classification

Management of OCD lesions is based primarily on the status and stability of the overlying cartilage. The size and location of the lesion and the patency of the capitellar growth plate also influence decision making.23–25

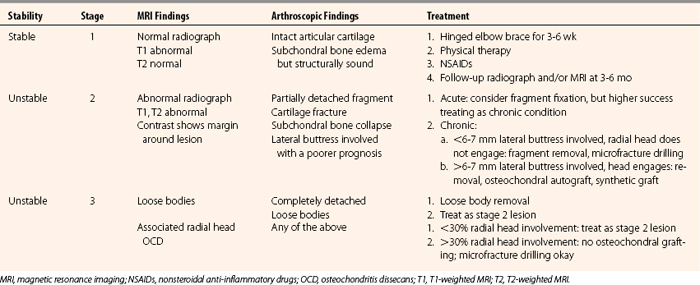

To guide treatment, detailed classification systems based on radiographic26,27 and arthroscopic23 findings have been delineated.28,29 We have simplified these algorithms into a three-stage classification that provides a template for management. Table 6-1 shows the classification.

Stage 1.

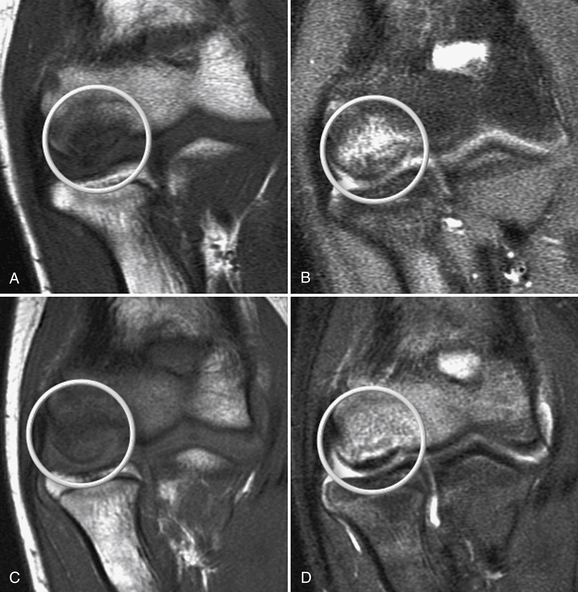

In stage 1, the osteochondral fragment is intact, stable, and not displaced. Radiographic findings are often negative. The MRI signal varies; it is typically abnormal on T1-weighted and normal on T2-weighted images, although the T2 signal may also be abnormal. Figure 6-7A and B shows a stage 1 lesion with coronal-slice signal that is abnormal on T1- and T2-weighted images. Arthroscopically, the articular cartilage is intact, with general preservation of subchondral stability.

This stage is best treated nonoperatively. All activity involving the affected arm should be stopped. The elbow should be rested in a hinged elbow brace for 3 to 6 weeks. Progressive physical therapy should ensue as symptoms abate. Return to sports usually can be expected at 3 to 6 months and should be governed by primarily by the patient’s clinical response, because radiographic changes often lag behind the clinical symptoms by several months or years. Nevertheless, follow-up radiographs and MRI scans should be obtained at 2- to 3-month intervals to track progress. Figure 6-7C and D shows the same patient as in Figure 6-7A and B at the 6-month follow-up assessment after conservative treatment, with clear reconstitution of the subchondral bone.

Stage 2.

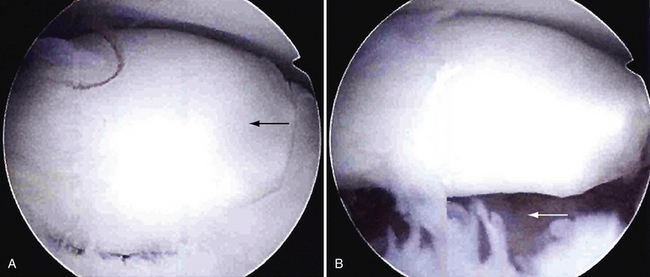

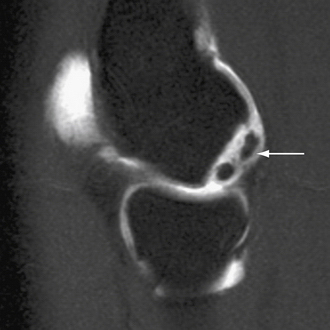

In stage 2, the osteochondral fragment is partially separated, as documented radiographically and arthroscopically. Radiographs demonstrate fissuring, lucencies, and fragmentation. On MRI, T1- and T2-weighted sequences show abnormal signal intensity and a margin around the fragment, denoting its instability (Fig. 6-8). Computed tomography (CT) may reveal the partially separated fragment. Arthroscopically, the cartilage is fractured, and the subchondral bone is unstable and partially displaced (Fig. 6-9).

When an unstable lesion is identified, conservative treatment should be bypassed. It warrants prompt surgical intervention to return the athlete to his or her sport or activities of daily living as soon as possible. In stage 2 lesions, the size and location of the lesion govern treatment. For smaller lesions, débridement is an option. Patients typically have immediate relief of symptoms, but the long-term natural history includes arthritis. Fragment fixation has been advocated by some for this stage, although questions linger concerning the long-term healing potential of fixed fragments and clinical results of the procedure.26,27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree