Osteoarthritis

Mary S. Walton

Carlos J. Lozada

Seth M. Berney

|

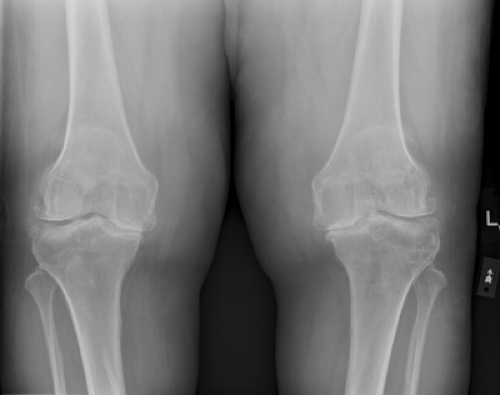

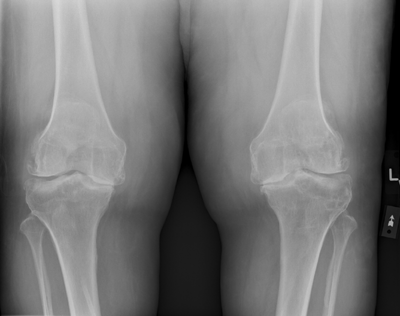

A 60-year-old male former professional football player with a history of multiple knee injuries complains of bilateral knee pain for 10 years. The patient also complains of bilateral wrist pain and 15 to 20 minutes of morning stiffness. He denies joint swelling, Raynaud’s phenomena, sicca symptoms, fever, or chills.

On physical examination, he is a non–ill-appearing male with a nontender nodule on the right index distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint and bony enlargement of right long and left ring proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and DIP joints. He also has tenderness on palpation at the base of bilateral thumbs’ carpometacarpal (CMC) joints and enlargement of his bilateral knees with pain and crepitus on passive range of motion. His wrists, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, elbows, hips, and ankles are normal (Fig. 19.1).

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), also referred to as degenerative joint disease (DJD), is the most common form of joint disease in humans. Because of physician visits, medications, surgical intervention, and time missed from work, OA appears to cost as much as 30 times more than rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (1).

Osteoarthritis was once thought to be the result of aging. However, we now believe that it develops as a consequence of multiple factors, including biochemical and biomechanical abnormalities, as well as genetic predispositions manifesting clinically as OA.

Epidemiology

Osteoarthritis can be defined radiographically or clinically (radiographs plus clinical symptoms or signs). Utilizing radiographic criteria, 30% of individuals between the ages of 45 and 65 are affected, and more than 80% are affected by their eighth decade of life.

The prevalence of OA increases in both men and women as they age, but gender differences exist. Osteoarthritis affects men more commonly among patients younger than 45 years and women more commonly among patients older than 55 years. Additionally, DIP OA is ten times more likely in women than in men. Mothers and sisters of women with DIP OA are two to three times more likely to be affected by it (2).

Obesity in women has been linked to OA of the knees and hip (3) and is probably also a risk factor for knee OA in men Obesity is also a risk factor for hand OA in both genders. The mechanisms for this have not been clearly elucidated and may include increase in body mass, altered biomechanics of gait, genetic predisposition, and/or altered metabolism. We also cannot adequately explain the association between obesity and OA of non–weight-bearing joints such as the sternoclavicular and DIP joints.

Pathogenesis

Initially thought of as a disease only of articular cartilage, OA involves the entire joint, including the subchondral bone. Because the role of inflammation in OA with increased expression of cytokines and metalloproteinases in synovium and cartilage is becoming more recognized, the term degenerative joint disease is no longer appropriate when referring to OA. Furthermore, the contention that OA is “noninflammatory” is incorrect, while “mildly inflammatory” would be a more accurate description.

The etiopathogenesis of OA has been divided into three stages (5). During stage 1, increased production of proteolytic enzymes such as metalloproteinases (e.g., collagenase and stromelysin) destroys the cartilage matrix. During stage 2, the cartilage surface erodes and fibrillates, releasing proteoglycans and collagen fragments into the synovial fluid. Finally, in stage 3, these cartilage breakdown products induce a chronic inflammatory response in the synovium, characterized by macrophage production of interleukin 1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), and metalloproteinases. These substances probably increase the cartilage ulcerations and may stimulate chondrocytes to produce more metalloproteinases, resulting in cartilage loss and bony eburnation and ultimately subchondral bone osteophyte formation.

Clinical Presentation

The initial goal of the health care professional when seeing a patient with joint pain is to differentiate OA from more inflammatory arthritides, such as RA.

In contrast to OA, RA primarily affects the wrists, MCP joints, and PIP joints (PIP), and spares the DIP joints and thoracic and lumbosacral spine. Rheumatoid arthritis is also typically associated with inflammatory morning stiffness (more than 1 hour) and radiographic findings of bone loss (periarticular osteopenia; marginal erosions of bone) rather than bone formation.

Clinical Points

What Differentiates OA From RA

Asymmetric joint involvement

Bony joint enlargement (not joint swelling)

New bone formation (osteophytes)

Morning stiffness <45 to 60 minutes

Involvement of DIP joints, PIP joints, and/or spine; sparing MCP joints

Symptomatic hip OA is usually insidious in onset and may cause diminished internal rotation, a limp, and groin or buttock pain. However, not uncommonly, patients may experience low back pain or medial knee pain, representing pain referred from the hip. Pain in the lateral aspect of the thigh, around the greater trochanter that is usually reproducible on palpation, usually represents greater trochanteric bursitis, not OA.

Osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine can cause spinal stenosis. These symptoms may include pseudoclaudication with intermittent or constant pain in the legs worsened by exertion (particularly when the patient stands straight up or hyperextends the back, such as descending stairs) and relieved by flexing the back, sitting, or walking upstairs.

Erosive OA, a disorder occurring primarily in women, causes inflammation of the DIP or PIP joints, resulting in a central joint erosion (described as “seagulls” on radiograph).

Multiple causes of secondary OA exist, including joint trauma (fractures or surgeries), prior inflammatory arthropathy, Paget disease, hemophilia, multiple endocrinopathies, neuropathic or Charcot joints, and congenital or hypermobility disorders.

The disease progression is characteristically slow, over years or decades. Eventually, these events alter the joint architecture, and additional bone grows as it remodels to stabilize the joint.

History: pain without swelling (synovitis) and morning stiffness <45 minutes

Physical examination findings: bony enlargement without synovitis commonly involving DIP, PIP, first CMC joints, AC joint of shoulder, hips, knees, first MTP joints, facet joints of the cervical and lumbar spine

Laboratory: Normal laboratory studies; joint effusion will be noninflammatory with <2,000 WBC/mm3

Radiographic: Asymmetric joint space narrowing; asymmetric joint involvement; osteophytes

Examination

The physical examination findings are limited to the affected joints. On inspection, there may be bony enlargement and malalignment (such as angulation of the PIP, DIP, or knee joints) depending on disease severity. Heberden’s and/or Bouchard’s nodes (compressed fibrogelatinous cysts) overlying the DIP and PIP joints, respectively, may develop and inflame (Fig. 19.2).

A noninflammatory joint effusion (defined as a WBC count of 200 to 2,000 WBC/mm3) may occur, usually without significant joint erythema or warmth. Patients have pain on active or passive range of motion of the affected joints. Crepitus (a grating or grinding sensation that occurs as the joint is moving) is characteristic of larger joints, such as the knees. Limitation of joint motion may be present in more advanced cases, as well as periarticular muscle atrophy secondary to disuse.

Diagnostic Studies

Osteoarthritis typically does not cause any conventional laboratory abnormalities other than a noninflammatory synovial fluid analysis (a leukocyte cell count of 200 to 2,000/mm3, with a mononuclear predominance). In contrast, the laboratory findings in RA correlate with systemic inflammation and commonly include elevated acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein) and the “anemia of chronic disease.” Eighty percent of patients eventually have a positive serum rheumatoid factor. Inflammatory joint fluid (WBC >2,000 cells/mm3 with a polymorphonuclear cell predominance) further differentiates the two diseases.

Radiographic findings most indicative of OA are bony growths at the joint margins known as osteophytes (colloquially known as “bone spurs”). Other findings include asymmetric joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cyst formation. The severity of the radiographic findings often fails to correlate with symptoms until the joint space is obliterated. When radiographing knees and hips, weight-bearing (or upright) views result in a more realistic image of the joint.

Treatment

The management of OA includes preventive and therapeutic (nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic) components.

Preventive Therapy

Although many of the presently established risk factors, such as increasing age and genetics, cannot be altered, the single most important modifiable factor emerging from epidemiologic trials is obesity.

Weight loss should be a goal in patients who are obese because even modest weight loss has been accompanied by, at times, a dramatic improvement in back and lower extremity symptoms.

Differential Diagnoses to Consider

Inflammatory versus noninflammatory

Synovitis (joint inflammation) versus bony enlargement

Differential Diagnoses

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree