21

Orthopedic Management of the Shoulder

1. Identify and describe methods, management, and rehabilitation for subacromial rotator cuff impingement.

2. Identify and describe methods of management and rehabilitation for tears of the rotator cuff.

3. Describe methods of management and rehabilitation for glenohumeral instability.

4. Discuss methods of management and rehabilitation for adhesive capsulitis.

5. Identify and describe common injuries of the acromioclavicular joint.

6. Describe common methods of management and rehabilitation for injuries of the acromioclavicular joint.

7. Identify and describe common fractures of the scapula, clavicle, and proximal humerus.

8. Outline and describe methods of management and rehabilitation of fractures around the shoulder.

9. Describe methods of management and rehabilitation after shoulder arthroplasty.

10. Describe common manual exercise techniques for the shoulder.

SUBACROMIAL ROTATOR CUFF IMPINGEMENT

A common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction in laborers, athletes, and persons who do repetitive overhead lifting is subacromial rotator cuff impingement. In this disorder, the tendons of the rotator cuff are crowded, buttressed, or compressed under the coracoacromial arch, resulting in mechanical wear, stress, and friction.15,20,23 Clinically, distinction must be made between primary and secondary impingement because there are important differences in treatment related to the specific cause of impingement.15,20

Primary shoulder impingement refers to mechanical compression of the rotator cuff tendons, primarily the supraspinatus tendon, as they pass under the coracoacromial ligament between the acromion and coracoid process.15,32

Secondary shoulder impingement is related to glenohumeral instability that creates a reduced subacromial space because the humeral head elevates and minimizes the area under the coracoacromial ligament.20 This mechanical instability is the result of impairment of muscle coordination and weakness of the scapular stabilizers.

Age-related degenerative changes also can result in a decreased subacromial margin between the rotator cuff and coracoacromial arch. Bony osteophyte formation can occupy space under the anteroinferior surface of the acromion, which consequently reduces the available space. A reduction in available space in the shoulder is known as anatomic crowding. The supraspinatus tendon is the most common structure involved with rotator cuff impingement; the vascularity of the supraspinatus tendon is causative.20,32 An area just proximal to the insertion on the greater tuberosity is hypovascular and is commonly referred to as a watershed zone, critical zone, or critical portion. This area of relative transient hypovascularity occurs with repeated arm motions from abduction to adduction, which compromises the blood supply to the area. The combination of reduced blood supply to the supraspinatus tendon and mechanical wear, stress, and friction as a result of repeated overhead motions can lead to primary impingement, supraspinatus tendinitis, and ultimately tears within the rotator cuff.27,32

The various stages of rotator cuff impingement are related to age and degenerative changes in the cuff itself. Neer35 has identified three specific stages of impingement (tendinitis):

Stage I: Occurs in younger patients (usually younger than 25 years of age), but can occur at any age. Clinical features are edema and hemorrhage. Pain is worse with shoulder abduction greater than 90°.2–5 It is essentially a reversible lesion that responds to conservative physical therapy interventions.37

Stage I: Occurs in younger patients (usually younger than 25 years of age), but can occur at any age. Clinical features are edema and hemorrhage. Pain is worse with shoulder abduction greater than 90°.2–5 It is essentially a reversible lesion that responds to conservative physical therapy interventions.37

Stage II: The fibrosis and tendinitis stage, which usually affects patients between the ages of 25 and 40 years.1 It is classified as irreversible because of long-term repeated stress, wherein the supraspinatus tendon, biceps tendon, and subacromial bursa become fibrotic. Pain is the predominant feature and occurs with daily activities; it frequently causes the patient difficulty at night.

Stage II: The fibrosis and tendinitis stage, which usually affects patients between the ages of 25 and 40 years.1 It is classified as irreversible because of long-term repeated stress, wherein the supraspinatus tendon, biceps tendon, and subacromial bursa become fibrotic. Pain is the predominant feature and occurs with daily activities; it frequently causes the patient difficulty at night.

Stage III: Affects patients more than 40 years of age. It is characterized by tendon degeneration, rotator cuff tears, and rotator cuff ruptures. Usually associated with a long history of repeated shoulder pain and dysfunction, as well as significant muscle weakness and atrophy.

Stage III: Affects patients more than 40 years of age. It is characterized by tendon degeneration, rotator cuff tears, and rotator cuff ruptures. Usually associated with a long history of repeated shoulder pain and dysfunction, as well as significant muscle weakness and atrophy.

Various clinical tests can be used to identify the presence of pain related to specific maneuvers of the shoulder. During the initial evaluation performed by the physical therapist (PT), tests are used to elicit impingement signs. One of these is the Neer painful arc test, in which pain is reported while the shoulder goes through elevation with internal rotation. This test elicits impingement secondary to compression of the rotator cuff against the coracoacromial arch.10 The Hawkins-Kennedy test is performed by elevating the shoulder to 90° in the scapular plane with internal rotation over pressure (Fig. 21-1). In most cases, elevation of more than 80° or 90° elicits pain. Therefore exercise and all activities that require the shoulder to elevate or abduct past 80° or 90° must be strictly avoided until all symptoms of pain have been eliminated.

Rehabilitation of Primary and Secondary Rotator Cuff Impingement

Kamkar and colleagues20 have identified scapular weakness as leading to “function scapular instability,” which affects scapular position during activities that cause a “relative decrease in the subacromial space.” This secondary impingement requires the scapulothoracic muscles to be strengthened and stabilized before specific rotator cuff weakness can be addressed. Scapula thoracic articulation is known to many clinicians as the true core of the upper extremity. To effectively stabilize the humeral head so that it does not migrate superiorly, causing “winging” or “tipping,” the scapular muscles (serratus anterior; upper, middle, and lower trapezius; levator scapulae; and rhomboid muscles) must be strengthened.17,20,42 Thein42 describes the clinical features of humeral head migration (secondary impingement) as possibly confusing the typical impingement picture. She reports, “If the supraspinatus is overworked trying to stabilize the humeral head, then it is unable to effectively function to depress the humeral head. The resultant upward movement decreases the subacromial space and irritates the subacromial soft tissues, thus perpetuating the impingement process.”

Scapular stabilization exercises are only one component of a successful rehabilitation program.9 In general a comprehensive rehabilitation program to address rotator cuff impingement, rotator cuff tendinitis (supraspinatus tendinitis), and degenerative tears of the rotator cuff tendons include modification of activities, local and systemic methods to control pain and swelling (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], corticosteroid injections, ice, ultrasound, iontophoresis, phonophoresis), stretching and strengthening exercises, and a return to normal function after reevaluation by the PT and with continued maintenance of protective positions and general conditioning.13,15

Throughout phase I, stretching exercises are performed to increase blood flow and contractility15 and improve motion. The PTA must pay particular attention to performing all stretching activities, because many generalized shoulder stretches involve full forward shoulder elevation and abduction maneuvers. All phase I stretching should encourage nonballistic, slow, controlled, pain-free motion at less than 80° to 90° of elevation. Capsular mobility has been shown to be very helpful in increasing motion and preparing the surrounding muscles to assist in shoulder elevation in all planes of motion.26,34 However, once symptoms are managed the patient can perform all stretches involving elevation and abduction if these stretches do not produce symptoms. Depending on the initial evaluation data gathered by the PT, the patient may be instructed in two specific stretches that authorities15 suggest are effective in addressing posterior capsular tightness. Shoulder adduction across the chest (cross-body stretching) and internal shoulder rotation are used cautiously to improve posterior capsular tightness and overcome the limitations on motion of internal rotation of the shoulder. The effective use of the sleeper stretch to increase posterior capsular mobility has been reported. The concept of anterior capsular mobility has been presented as important for shoulder mobility to treat or prevent impingement while regaining horizontal abduction to prepare for tri-plane overhead motion.25

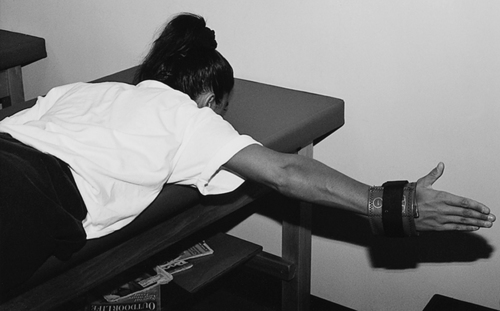

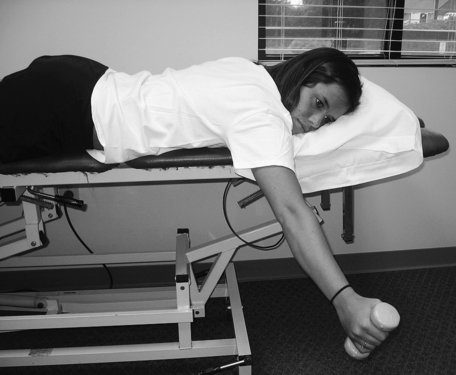

Initial strengthening activities that can begin during phase I generally include scapula stabilization exercises and light rotator cuff strengthening. The use of closed kinetic chain loading such as wall push-ups can be an effective pain-free low level muscle recruitment exercise. Closed kinetic chain (CKC) exercises will provide co-contraction and tri-plane stabilization with lower muscle contraction load than open kinetic (OKC) chain exercises.5,46 Once the patient demonstrates improved motion and can do ADLs without pain, a progression through a series of OKC muscle strengthening can begin. Prone extension to the hip, side-lying external rotation, and scaption elevation without pain are some recommended exercises for rotator cuff recruitment toward strengthening (Fig. 21-2).38 Specific rotator cuff strengthening exercises should focus on the supraspinatus muscle.38 Studies demonstrate that the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, deltoid, latissimus dorsi, and pectoral muscles are effectively strengthened by arm elevation in the transverse plane, shoulder elevation with neutral rotation in the plane of the scapula (Fig. 21-3), prone horizontal shoulder abduction with external rotation (Fig. 21-4), and seated press-ups.30

Phase II, return to function, progresses with advanced scapular stabilization exercises that are encouraged as part of a comprehensive glenohumeral and scapulothoracic strengthening program. This phase of program uses progressive resistive strengthening via increased resistance while using OKC exercises. Electromyographic studies33 have identified four basic scapular stabilization exercises that strengthen the upper, middle, and lower trapezius; the levator scapula; the rhomboid major; the pectoralis minor; and the middle and lower serratus anterior muscles.8 The exercises are rowing, scapular plane elevation (scaption), press-ups, and push-ups followed by scapular protraction. As strength improves and when motion increases, a gradual return to normal function signifies the beginning of phase III, return to activity.44

The process of functional recovery is slow and must be done cautiously; overhead activities are introduced incrementally as the patient is able to demonstrate pain-free motion and the ability to perform strengthening activities. Some advanced return to activity phase exercises can include oscillatory training (Bodyblade) using tri-plane positioning (Fig. 21-5).40

Surgical Management of Shoulder Impingement and Rotator Cuff Tears

When physical therapy interventions fail to provide long-lasting relief and in cases of rotator cuff tears (Neer’s stage III impingement, tendon degeneration, and cuff tears), various surgical procedures can be used to correct the underlying pathologic condition. With subacromial impingement not involving a specific rotator cuff tear, subacromial decompression (SAD) can be used to eliminate or diminish the abnormality causing the impingement between the humeral head and the undersurface of the acromion, allowing freer movement of the tendons without irritation. Acromioplasty includes beveling or reshaping of the acromion with detachment of the coracoacromial ligament. Distal clavicle excision (DCE) may also be involved.39 If there is an associated rotator cuff tear (small tear less than 1 cm, medium tear less than 3 cm, large tear greater than 5 cm), a SAD procedure is used in conjunction with direct repair of the rotator cuff defect. The SAD procedure can be performed as an open arthrotomy or as an arthroscopic procedure.39

Rehabilitation after SAD or rotator cuff repair closely parallels nonoperative rehabilitation of rotator cuff impingement. However, time must be allowed for healing of the soft tissues and bone after surgery. Some clearly identified differences exist between rehabilitation procedures used for decompression and small cuff tears (less than 1 cm) and repairs of medium (less than 2 to 3 cm) and large (greater than 4 to 5 cm) cuff tears with SAD.39 With a small cuff tear repaired in conjunction with a decompression procedure, active motion and pain-free exercise can begin as soon as the patient can tolerate these activities.39,44 However, if the rotator cuff tear is between 2 and 5 cm, tissue protection must be longer to allow for extensive soft-tissue healing. If full active range of motion (AROM) is allowed too early, healing of the rotator cuff may be compromised because of the stresses placed on the repaired tissues. The type of surgical procedure used, mini-open procedure or arthroscopic approach; the healing constraints must be considered for proper beginning of successful rehabilitation. Large cuff tears may require longer periods of time for recovery to achieve improved healing.15

Generally, recovery after SAD with or without rotator cuff repair follows a prescribed three-phase rehabilitation program.42,44 Phase I, the prefunctional phase, lasts approximately 3 to 4 weeks39,44 and focuses on control of pain and swelling with NSAIDs, oral analgesics, ice packs, ultrasound, phonophoresis (if needed), infrared therapy, and various degrees and durations of manual range of motion (ROM), depending on the extent of tissue injury. The concept of early protected manual motion applies depending on the precise nature of the injury and which surgical procedure is used. The prefunctional phase should include increasing ROM, scapula stabilization beginning with retraction, and adding protraction when the patient has pain-free arm control.

At the end of this phase, the initial use of the upper body ergometer (UBE) may be introduced. The early use of CKC activity with double-arm wall push-ups may be helpful for low level recruitment of shoulder muscles.44,46 With increased arm control strength and motion, phase II, the return to function phase, can begin. It generally lasts from weeks 5 through 12 after surgery. During this phase, progressive motion can be used, although with caution for repetitive shoulder abduction and forward elevation above 90°. The use of Thera-Band strengthening of the rotator cuff should be performed in a short-arc pattern of motion, normally in the standing positions.18,44 In addition, dumbbell isotonic concentric and eccentric exercises for recruitment of the humeral head decompression (rotator cuff) may begin using short-arc pain-free ROM. This program is known as positional recruitment for the purpose of low-level strengthening and progresses according to the tolerance of the patent and demonstration of arm control.44 During phase II, progressive strengthening exercises for elevation in scaption are performed in allowing for what is known as shoulder hike. Prone positional exercise, such as prone extension to hip (Fig. 21-6) and short-arc prone scaption at 100°, and eccentric training of scaption has been very useful in treating shoulder hike.30,38,44 Progressive resistive exercises (PREs) are a major part of the return to function phase. With some patients, based on good pain-free response to all rotator cuff exercise, advanced scapula stabilization and oscillatory training such as the Bodyblade may begin (see Fig. 21-5).

Phase III, the return to activity phase, can begin once the patient can demonstrate normal motion without symptoms and with improved strength. This phase lasts approximately from week 12 to beyond. Return to activity always includes the continuation of PREs. This aspect of rehabilitation is for the long haul.44 Advanced CKC exercises such as single-arm wall push-ups on an uneven surface may be introduced. For the advanced patient, plyometric activity with plyo-toss exercise may be used (Fig. 21-7).

During the return to activity phase the core rotator cuff strengthening exercises of forward elevation, scaption, prone horizontal abduction with external rotation, and press-ups, as well as scapular stabilization exercises of seated rows, prone scaption at 120° (Fig. 21-8), scaption, and press-ups for scapular protraction (push-ups with a plus)20,33,38,44 form the foundation of improving strength that eventually leads to full functional recovery.

The prefunctional phases and periods of passive or manual control motion are extensive for rehabilitation after surgical repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Generally, no active shoulder motion or active concentric or eccentric strengthening is allowed for 2 to 3 months after surgery.11 Extensive soft-tissue healing must proceed unabated to foster the recovery of functional motion and strength.

Initially the patient is placed in abduction pillow or shoulder immobilization after surgery to allow the repaired tissues of the rotator cuff and deltoid to be placed in a shortened position. Early active muscle strengthening and active motion are avoided to allow for appropriate healing. Generally, manual control passive ROM with full motion restriction is allowed during the first several weeks of recovery. AAROM activities, can begin 2 months after surgery.11

Submaximal isometrics and scapular stabilization exercises must be added cautiously 4 to 12 weeks after surgery.11,44 Specific rotator cuff strengthening exercises11 performed isotonically with dumbbells, Thera-Band, and similar devices are reserved until 3 months after surgery to accommodate the healing constraints of the tendons and muscles of the rotator cuff and deltoid. Full functional recovery of motion and strength may take up to several months after the repair of massive rotator cuff tears.11,44

GLENOHUMERAL JOINT INSTABILITY AND DISLOCATION

Dislocations and subluxations (partial dislocation) of the glenohumeral joint (the articulation between the humeral head and glenoid fossa of the scapula) frequently occur after indirect trauma with the arm abducted, elevated, and internally rotated (posterior dislocation).16 The shoulder is the most commonly dislocated joint in the body,16 and dislocation occurs in men more often than in women. Anterior dislocations occur more frequently than posterior dislocations.16 Also, rotator cuff tears of various dimensions (small, less than 1 cm; medium, less than 3 cm; and large, greater than 5 cm) occur with relative frequency. Strege41 reports that rotator cuff tears occur 30% of the time with acute anterior dislocations in patients older than 40 years of age and 80% of the time in patients older than 60 years of age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree