17

Orthopedic Management of the Ankle, Foot, and Toes

Walter L. Jenkins and D.S. Blaise Williams

1. Identify common foot and ankle ligament injuries.

2. Describe intervention methods for common foot and ankle ligament injuries.

3. Identify and describe common lower leg, ankle, and foot tendon injuries.

4. Outline and describe common methods of intervention for lower leg, ankle, and foot injuries.

5. Identify common foot and ankle fractures.

6. Discuss common methods of intervention for foot and ankle fractures.

7. Identify and describe common methods of intervention for toe injuries.

8. Describe common mobilization techniques for the ankle, foot, and toe.

LIGAMENT INJURIES OF THE ANKLE

Injuries to the lateral ligament complex (the anterior talofibular ligament, fibulocalcaneal ligament, and posterior talofibular ligament) account for approximately 14% to 25% of all sports-related injuries.34,62 Therefore inversion ankle sprains are among the most common sports and orthopedic injuries.31,32,91 Studies report that approximately 95% of all ankle sprains occur to the lateral ligament complex.92 Additionally, injuries to associated structures including articular cartilage and the synovial membrane have been identified on arthroscopy in individuals who had recurrent or recalcitrant lateral ankle sprains.59 Untreated ankle sprains may lead to chronic pain, muscular weakness, and instability.32 Ankle joint osteoarthritis has been observed in patients with chronic ankle instability.108

Lateral Ligament Injuries (Inversion Ankle Sprains)

Mechanisms of Injury

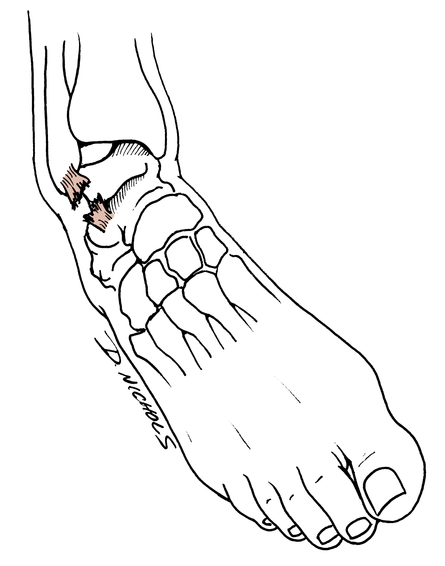

Ligament sprains of the lateral aspect of the ankle usually are caused by plantar flexion, inversion, and adduction of the foot and ankle (Fig. 17-1).97 Large forces are not needed to produce an ankle sprain. Stepping off a curb, stepping into a small hole, or stepping on a rock can produce sudden plantar flexion and inversion motions. During athletic competition, stepping on an opponent’s foot is a common occurrence that leads to lateral ligament sprains of the ankle. Most commonly ankle sprains occur with the foot is in an unloaded or non–weight-bearing (NWB) position before the injury.104

Classification of Sprains

Classifying inversion ankle sprains can be difficult and confusing.97 The standard classification of ligament injuries (e.g., first-, second-, and third-degree sprains) requires elaboration when applied to inversion ankle sprains, specifically addressing grades, degrees, and descriptive severity of the injury (mild, moderate, or severe). A classification model described by Leach64 is contrasted with the common standard classification of ankle sprains as a means of comparison and to illustrate the potential for confusion about classification of inversion ankle sprains.

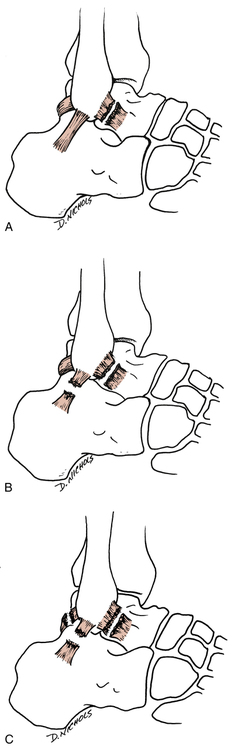

First-degree sprain: Single ligament rupture.64 The anterior talofibular ligament is completely torn. In the standard classification of ligament sprains a complete tear or rupture of a ligament is called a grade III, or third-degree sprain (Fig. 17-2, A).

First-degree sprain: Single ligament rupture.64 The anterior talofibular ligament is completely torn. In the standard classification of ligament sprains a complete tear or rupture of a ligament is called a grade III, or third-degree sprain (Fig. 17-2, A).

Second-degree sprain: Double ligament rupture.64 Both the anterior talofibular ligaments and fibulocalcaneal ligaments are completely torn. The standard classification describes a partially torn single ligament as a grade II sprain (Fig. 17-2, B).

Second-degree sprain: Double ligament rupture.64 Both the anterior talofibular ligaments and fibulocalcaneal ligaments are completely torn. The standard classification describes a partially torn single ligament as a grade II sprain (Fig. 17-2, B).

Third-degree sprain: All three lateral ankle ligaments (anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular, and fibulocalcaneal) are completely torn.64 In the standard classification, a single ligament that is completely torn is defined as a grade III ligament sprain (Fig. 17-2, C).

Third-degree sprain: All three lateral ankle ligaments (anterior talofibular, posterior talofibular, and fibulocalcaneal) are completely torn.64 In the standard classification, a single ligament that is completely torn is defined as a grade III ligament sprain (Fig. 17-2, C).

Clinical Examination

Testing

Ankle stability tests are used by the physician and the physical therapist (PT) to identify and quantify the integrity of the lateral ligament complex. Injury to the anterior talofibular ligament can be assessed clinically by performing the anterior drawer test (Fig. 17-3).97 The patient must be in a relaxed seated or semirecumbent position with the involved leg flexed 90° at the knee and the involved ankle slightly plantar flexed. Stabilize the distal tibia and support it with one hand, while using the other hand to gently but firmly grasp the calcaneus and attempt to translate or pull the ankle forward. No excessive motion is seen or felt if the ligament is intact. However, the ankle demonstrates excessive forward or anterior motion if the anterior talofibular ligament is torn.

The talar tilt test or inversion stress test examines the ankle ligament’s resistance to maximal inversion stress (Fig. 17-4).97 The patient is in the same position used for the anterior drawer test, and the ankle is gradually stressed by exertion of constant pressure over the lateral aspect of the foot and ankle while counter pressure is applied over the inner aspect of the lower leg until maximal inversion is reached.10 The severity of ligament injury should be graded according to the classification system used by the physician or the supervising PT.

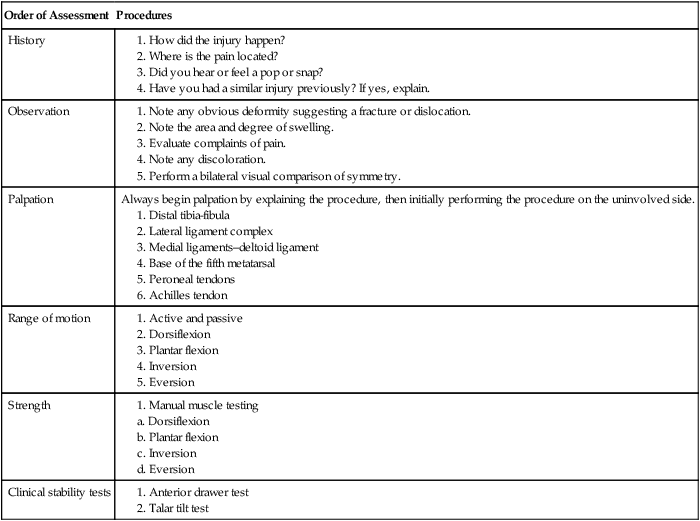

Order of procedures

Table 17-1 outlines the procedure for evaluation of inversion ankle sprains. The mechanism of injury that produces an inversion ankle sprain also may cause other conditions that must be differentiated by the physician91,97 and PT, such as fracture of the base of the fifth metatarsal, malleolar fractures, osteochondral fractures, osteochondritis dissecans, midfoot ligament sprains, and subluxing peroneal tendons.

Table 17-1

Physical Therapist Initial Evaluation Outline for the Clinical Assessment of Inversion Ankle Sprains

| Order of Assessment | Procedures |

| History | |

| Observation | |

| Palpation | Always begin palpation by explaining the procedure, then initially performing the procedure on the uninvolved side. |

| Range of motion | |

| Strength | |

| Clinical stability tests |

Intervention

The specific rehabilitation program used to treat inversion sprains depends on the severity of sprain (first-, second-, or third-degree). Generally first- and second-degree sprains can be effectively managed nonoperatively with a supervised rehabilitation program.98

Initial management of acute inversion ankle sprains calls for rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). Rest is a relative term used to define avoidance of unwanted stress; it does not necessarily require complete avoidance of all stress. The application of ice, compression, and elevation is directed at minimizing and reducing intense inflammatory response, hemorrhage, swelling, pain, and cellular metabolism to provide the most conducive environment for tissue healing.91

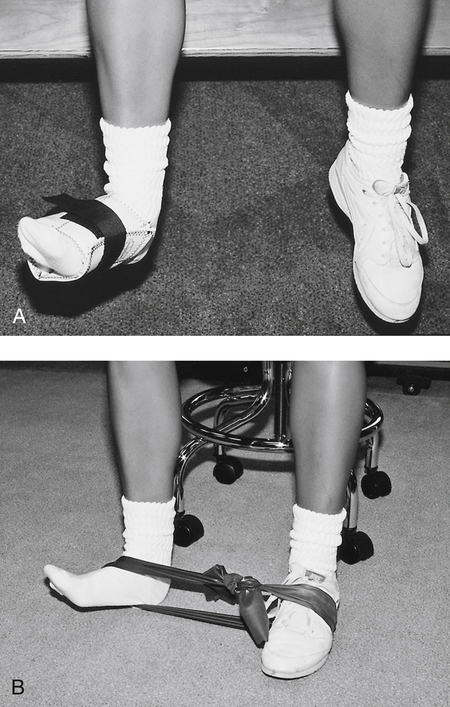

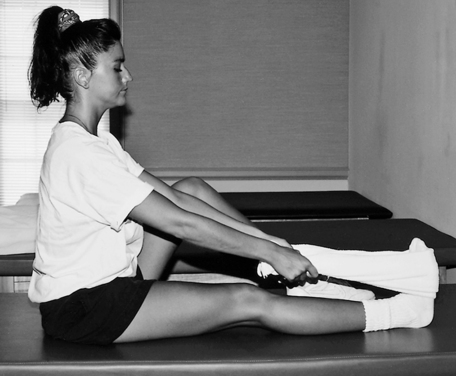

The moderate-protection phase can begin once the patient can bear weight on the injured limb without crutches, perform all ROM and isometric exercises without undue complaints of pain, and control the swelling. This phase encourages the use of the RICE principle, full weight bearing (FWB), and continued ligament support with the use of braces or tape. More progressive exercises are initiated, including concentric and eccentric contractions (Fig. 17-5) (with ankle weights or latex bands), heel cord stretching (Fig. 17-6) (towel stretch, wall stretch, or prostretch), and standing toe and heel raises.

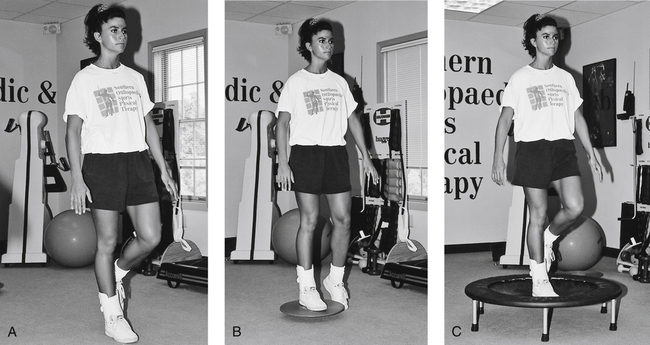

Proprioception exercises are commonly initiated during the moderate-protection phase. Protection of the ligament must be encouraged during these challenging exercises. Balancing on the injured limb on a flat surface is slowly progressed to a balance board, and then to a minitrampoline—all excellent exercises that stimulate balance, coordination, and muscular endurance (Fig. 17-7).

The minimum-protection phase can begin once the patient can perform all resistive exercises, (ankle weight, Thera-Band, and manual resistance) ambulate without pain or limping, and swelling is reduced. Although proprioception training is commonly used in practice there are few articles outlining its effectiveness in rehabilitation.115

From 4 to 8 weeks after injury, new collagen formation allows almost-normal stresses to be applied.91 At this point, more functional activities are allowed, including straight-line jogging, large figure-of-eight running, jumping drills, and cutting activities.

The minimum-protection phase does not imply removal of all supportive devices. Maturation of the injured ligaments can take as long as 6 to 12 months.91 Therefore it is critical to encourage patient compliance with the use of either tape or a semirigid brace during all running activities.

Box 17-1 outlines a general three-phase rehabilitation program for an inversion ankle sprain. In all instances, if pain, swelling, or irritation persists, the patient is not taken to the next phase until he or she is pain free in the present phase. The ankle must be securely taped or braced when running, jumping, or otherwise performing aggressive, ballistic motions.

The treatment of grade III ankle sprains (using the standard classification) is somewhat controversial.91,98 At this time there are few, if any outcome studies that outline differences in conservative and surgical treatment for acute grade III injuries. Kerkhoffs and associates56 concluded that “there is insufficient evidence available from randomized controlled trials to determine the relative effectiveness of surgical and conservative treatment for acute injuries of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle.” Some authors10,12,103 report that surgery is needed because “surgical exploration often reveals that the torn ends of the fibulocalcaneal ligament are so widely separated that simple immobilization alone is not sufficient to allow the ligament to heal in a stable position.”10 However, other authors have found that “early controlled mobilization (functional treatment) was the method of choice and provided the quickest recovery in ankle mobility and the earliest return to work and physical activity without compromising the late mechanical stability of the ankle.”91 Therefore depending on the physician’s choice of treatment, a grade III sprain can be treated either surgically or with early controlled motion and supervised physical therapy. A good to excellent long-term prognosis can be expected in 80% to 90% of patients with grade III ankle sprains regardless of the intervention.54 However, if inadequate treatment is performed, chronic instability may occur leading to injuries to associated structures.31 Secondary to the possibility of chronic instability Ferran and Maffulli31 have proposed that athletes with acute grade III injuries be surgically treated.

Generally joint protection lasts longer with grade III ankle sprains than with grade I and II sprains. When these injuries are treated surgically, and postoperative immobilization is used, deleterious effects on muscle, bone, cartilage, tendons, and ligaments can be expected.1

Deltoid Ligament Sprains (Medial Ligament)

Acute isolated sprains of the deep and superficial layers of the deltoid ligament are rare, occurring in only 3% to 5% of all ankle sprains.91,92 It is clinically important to recognize that “complete deltoid ligament ruptures occur in combination with ankle fractures.”91

However, according to Hintermann and associates,43 sprains of the deltoid ligament appear to be more frequent than commonly recognized, leading to problems with posterior tibialis tendon dysfunction and chronic medial ankle instability. Fractures of the medial or lateral malleolus may cause disruption of the deltoid ligament.43

Intervention

Partial tears of the deltoid ligament are managed nonoperatively with physical therapy. Because complete ruptures occur with fractures, many authorities advocate surgical repair and fixation of the fracture fragments.14,20 However, some authors recommend casting, NWB for 6 weeks, then progressive weight bearing and physical therapy.38 In either case, rehabilitation focuses primarily on joint protection and the use of a semirigid orthosis.

High Ankle Sprain or Ankle Syndesmosis Injury

When the ankle is forced into dorsiflexion or rotation with the foot in a weight-bearing position, injury to the ankle syndesmosis commonly occurs. This mechanism of injury is prevalent in skiing, football, soccer, and other sport activities.68 Injury to the structures supporting the ankle syndesmosis, the anterior and posterior tibiotalar ligaments, the interosseus membrane, interosseus ligament, and the deltoid ligament, can result in an unstable distal tibiofibular articulation.68,86,89 Diagnostic testing for the high ankle sprain include the external rotation and squeeze tests, and various forms of diagnostic imaging.

Intervention

Treatment of these injuries may include immobilization, limitation of weight bearing, and surgery.68,86,89 A conservative approach to treatment and rehabilitation is necessary secondary to weight bearing being disruptive to the healing process for these ligaments. Chronic instability and arthritis commonly occur when this injury is mismanaged.89

Chronic Ankle Ligament Instabilities

The PTA, as an integral part of the rehabilitation team, must be aware of certain short- and long-term complications that may arise from acute or chronic ligament injuries of the ankle. Complications after surgical repair or conservative treatment of ankle sprains are common. Renstrom and Kannus91 report that 10% to 30% of patients have chronic symptoms of weakness, swelling, pain, and joint instability after inversion sprains. There are two types of instabilities associated with chronic ankle sprains: mechanical and functional.

Mechanical Instabilities

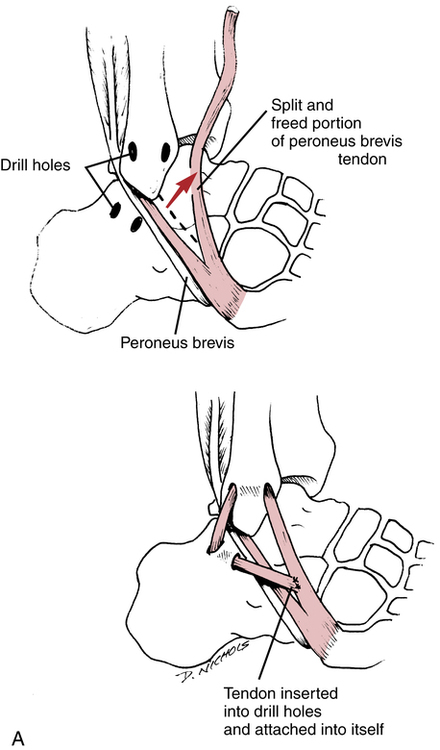

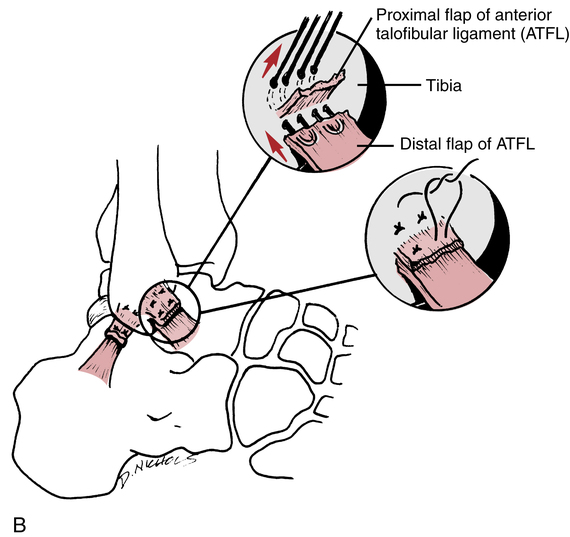

Mechanical instability is defined as laxity of the ankle ligaments. With mechanical instabilities, surgery may be necessary to stabilize the ankle joint.6 The Watson-Jones,117 Evans,30 Chrisman–Snook,17 and Elmslie17 procedures are common reconstructive surgical procedures used to help stabilize the lateral ligament complex of the ankle. In general, the peroneus brevis muscle is rerouted through a surgically constructed tunnel in the distal fibula (Fig. 17-8, A). The rerouting of the peroneus brevis dynamically stabilizes the lateral aspect of the ankle. Another method used to help stabilize chronic ligament laxity is a delayed anatomic repair of the ligaments. The ligaments are surgically cut, shortened, and reattached to the bone with this method (Fig. 17-8, B). Surgical repair has been gaining popularity among foot and ankle surgeons because of the failure of most reconstruction procedures to correct preinjury ankle biomechanics.44,70

Ankle arthroscopy has also been gaining popularity among foot and ankle surgeons secondary to the need to identify and treat intraarticular lesions at the time of surgery.21,59,70 In particular, articular cartilage lesions can be identified and treated with arthroscopy.

Functional Instabilities

Functional instability refers to a subjective feeling of giving way without affecting ligament laxity. Unlike mechanical instability, functional instability involves a host of factors, including strength, proprioception, and ligament stability. McVey and colleagues77 report that up to 40% of patients with lateral ankle instability have functional instability.

Intervention

The primary components of rehabilitation for chronic functional instabilities are closed-chain resistance exercises, proprioception maneuvers, dynamic muscular exercises (concentric and eccentric loads), and bracing for support. Single-leg support proprioception exercises with external resistance (Fig. 17-9) provide dynamic support and balance training. Balance board activities, heel-toe walking, and minitrampoline activities are the cornerstones of proprioception exercises for the ankle throughout all phases of rehabilitation for functional ankle instabilities.

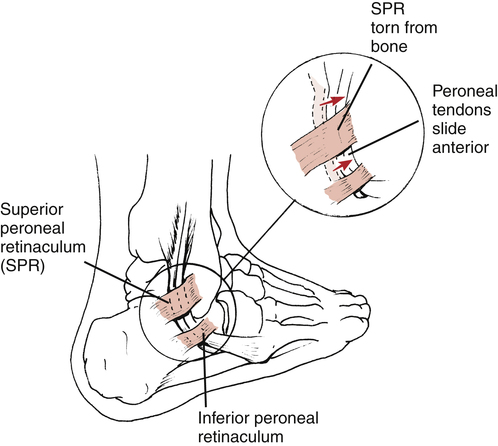

SUBLUXING PERONEAL TENDONS

The PTA must recognize that certain anatomic variations and acute injuries can result in instability of the peroneal tendons and ultimate disability. This injury is classified as acute or chronic. The mechanism of injury involves passive dorsiflexion with the foot slightly everted.27,73 Acute subluxation of the peroneal tendons can be misdiagnosed as a lateral ankle sprain because of the close anatomic proximity of the tendons to the lateral ligament complex (Fig. 17-10). Patients suffering with peroneal tendon subluxation commonly describe posterior ankle pain and may complain of a popping sensation in the lateral ankle. Active dorsiflexion with eversion of the ankle may reproduce the symptoms.41

Some patients who suffer dislocation of the peroneal tendons have a loose retinaculum (which supports the tendon within the peroneal groove) and also may have a very shallow peroneal groove.33 Acute injuries to the ankle ligaments (grades I, II, and III, using the traditional classification of sprains) may also result in injury to the peroneal retinaculum. Misdiagnosis of an ankle sprain is quite common.33 When subluxation occurs the peroneal tendons normally dislocate anteriorly over the lateral malleolus with ankle dorsiflexion.27,33,73

Intervention

Acute injuries usually are treated initially with conservative measures, including rigid-cast immobilization and NWB gait for approximately 6 weeks.33,105 Ferran and associates33 report that conservative management is successful in approximately 50% of cases. However, in some cases, patients ultimately require a surgical repair to correct the disability.55,105 Many authorities still recommend cast immobilization and NWB for 6 weeks for acute injuries, but operative care is the treatment of choice for cases involving recurrent or chronic subluxing peroneal tendons.55 Keene55 reports the five basic types of surgical repair procedures for correction of chronic subluxing peroneal tendons:

Postoperative Interventions

The postoperative care of subluxing peroneal tendons requires excellent communication among the PTA, PT, and surgeon. The exact procedure performed should be explained to the PT, who should articulate the key points of the surgery to the PTA and outline the indications and contraindications for rehabilitation. Usually postoperative care involves the use of immobilization for a few weeks and instruction in weight bearing as tolerated (WBAT). Keene55 recommends plantar flexion and dorsiflexion exercises 3 weeks after surgery. Heckman and colleagues41 suggest that patients remain non–weight bearing for 2 weeks followed by 2 to 4 weeks of immobilization in a cast or walking boot. ROM exercises are commonly initiated at 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively.

Initially, limited ROM dorsiflexion strengthening exercises should be used. As pain, swelling, and strength improve, greater degrees of dorsiflexion motion can be added. Proprioception exercises on a flat surface can be initiated soon after immobilization ends. Progression to balance board activities and minitrampoline exercises depends on the patient’s tolerance. Keene55 recommends that a running program can begin when ROM has been achieved and the involved limb reaches 80% of the strength of the noninvolved limb.

ACHILLES TENDINOPATHY

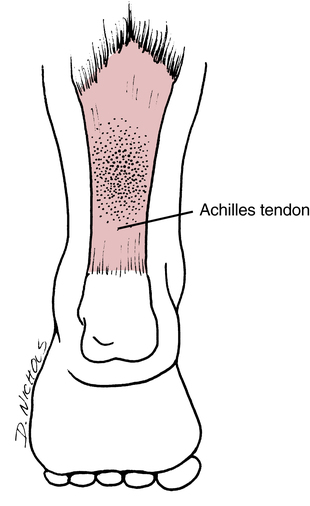

Achilles tendinopathy is an overuse injury resulting from repetitive microtrauma and accumulative overloading of the tendon (Fig. 17-11).55 The primary feature of Achilles tendinopathy is localized pain at the midportion, distal third, and insertion on the calcaneus. It should be distinguished from other similar posterior foot and ankle disorders such as retrocalcaneal bursitis and Haglund disease.101

Many intrinsic and extrinsic factors can lead to Achilles tendinopathy. Decreased vascularity, malalignment of the hindfoot or forefoot, and issues with gastrocnemius–soleus flexibility are common intrinsic factors.55,101 Extrinsic factors include variations in training, running surface changes, and poor or inappropriate footwear. The general features of Achilles tendinopathy include soft-tissue swelling, pain, and crepitus.