Chapter 41 Ophthalmology

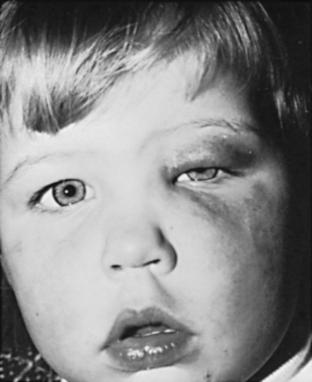

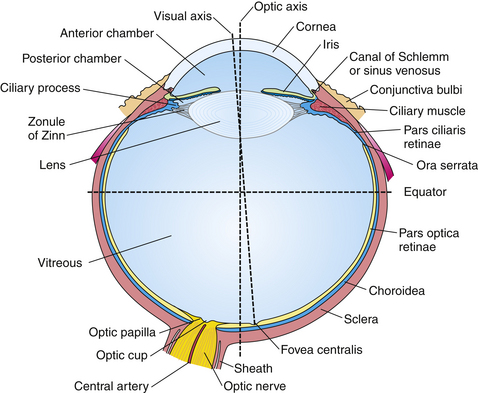

Patients present to the family physician with a limited set of symptoms, often with subtle differences to indicate mild or serious ocular conditions. To decide when to treat patients and when to refer them to an ophthalmologist, the family physician must possess a complete appreciation of these subtle differences. Knowledge of the basic anatomy of the eye is essential in determining these diagnostic differences (Fig. 41-1).

Figure 41-1 Anatomy of the right eyeball.

(From Scheie HG, Albert DM. Textbook of Ophthalmology, 9th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1977.)

Red Eye

Evaluation

Symptoms and Signs

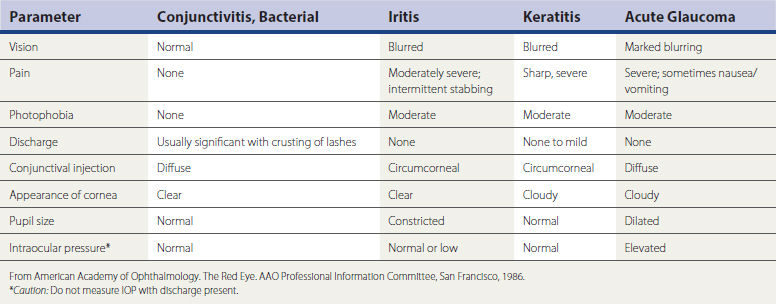

Patients who complain of a red eye generally can tell the physician whether the eye irritation occurred rapidly or progressed slowly. This information is important because a small foreign body, such as a grain of sand, lodged in the conjunctival sac produces a rapid hyperemia, whereas a viral or allergic conjunctivitis, or an iritis, generally produces a slowly progressive redness. Ocular pain is an important symptom (Table 41-1). Irritation of the superficial layer of the cornea, as caused by a small foreign body, is accompanied by a superficial “grain of sand” sensation in the eye. Deeper inflammatory processes, such as iritis or iridocyclitis, or a deeper penetrating foreign body in the cornea, present with more severe, dull pain in the eye.

Abnormal light sensitivity (photophobia) is a third danger symptom that must be elicited by the family physician. Photophobia occurs with corneal inflammation, iritis, and angle-closure glaucoma. Patients who have conjunctivitis usually do not have abnormal light sensitivity (Box 41-1).

Box 41-1 Approach to Patient Presenting with Red Eye (No History of Trauma)

Patients who complain of a red eye often complain of discharge from the eye (Table 41-2). If they do not complain of eye discharge spontaneously, the physician must inquire about the presence, type, and quantity of discharge. Purulent (creamy white or yellow watery) discharge suggests a bacterial cause. A serous or clear discharge suggests a viral cause. Scanty, white, stringy exudate occurs most often with allergic conjunctivitis. The absence of discharge indicates an unusual cause for red eye, such as iridocyclitis, ultraviolet (UV) light keratitis (snow blindness), or acute angle-closure glaucoma. A complaint of diminished visual acuity is a serious danger sign and must be elicited in the history.

Table 41-2 Conjunctivitis Clues

| Finding | Cause |

|---|---|

| Purulent discharge | Bacterial |

| Serous or clear discharge | Viral |

| Stringy, white discharge | Allergic |

| Preauricular lymph node enlargement | Viral |

Physical Examination

It is important to examine both eyes because many patients with conjunctivitis in one eye have clear signs of early conjunctivitis in the other. The type of infection must be closely inspected; conjunctival infection is characterized by individually visible vessels in the conjunctiva branching from the sclera toward the cornea, whereas ciliary infection appears as a red ring surrounding the cornea in which individual vessels are not clearly visible. The significance of ciliary infection is that the deep ciliary vessels are involved, indicating a much more serious inflammatory condition of the eye, such as a deep corneal infection, iritis, or iridocyclitis. Inspect the palpebral conjunctiva carefully with magnification to determine whether lymphoid hyperplasia (cobblestone appearance) exists. The type and quantity of discharge are assessed by pulling down the lower lid. The appearance of the punctum should be examined to determine whether pus is coming out of the tear duct. Palpation of the tear sac on the upper portion of the nose (lacrimal crest) demonstrates tenderness in cases of acute dacryocystitis.

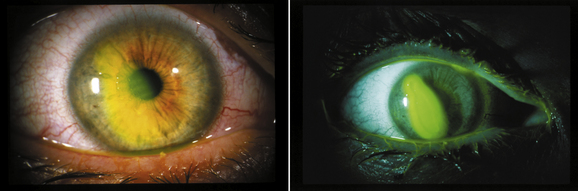

Carefully examine the cornea. Normally, the cornea is perfectly transparent. Excessive fluid within the stroma of the cornea results in partial opacification that can be observed by direct illumination with a penlight. A diffuse corneal haze can occur with congenital glaucoma and angle-closure glaucoma. After inspection with a penlight under magnification, perform corneal staining with fluorescein using sterile filter paper strips. The stained part of the strip is moistened with water and touched to the conjunctiva away from the cornea. With blinking, the fluorescein spreads over the cornea. A UV light source enhances fluorescence. Areas of bright-green staining denote absent or diseased epithelium. Corneal staining readily demonstrates a corneal abrasion and helps identify corneal foreign bodies and infectious epithelial defects, such as herpetic dendritic keratitis (Fig. 41-2).

Preauricular lymph node enlargement is a frequent sign of viral conjunctivitis and usually is not present with acute bacterial conjunctivitis (see Table 41-2).

Red Eye in Infants

Ophthalmia Neonatorum

Ophthalmia neonatorum is an infection or inflammation of the conjunctiva that occurs during the first 4 weeks of life. Possible causes include chemical conjunctivitis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and chlamydial infection. The increased incidence of venereal disease and shortcomings in silver nitrate prophylaxis are significant factors in the constantly evolving clinical picture. Ophthalmia neonatorum frequently is a manifestation of a systemic infection, requiring determination of the exact cause in all but the most transient cases. Table 41-3 outlines the management of the various types of ophthalmia neonatorum. At present, erythromycin is the medication of choice. Povidone-iodine ophthalmic solution (0.5%) is less toxic, inexpensive, and effective, but is not generally used because of confusion over povidone solution versus povidone soap.

Table 41-3 Management of Ophthalmia Neonatorum

| Disease | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Gonococcal conjunctivitis | ||

| Other bacterial conjunctivitis | ||

| Chlamydial conjunctivitis |

IM, Intramuscularly; bid, twice daily; qid, four times daily.

Silver nitrate has been replaced by erythromycin, so the incidence of chemical conjunctivitis has decreased significantly. Before the neonatal prophylaxis, gonorrhea was a common cause of ophthalmia neonatorum. Half of patients with gonococcal conjunctivitis develop corneal clouding, a major cause of blindness. Gonococcal conjunctivitis still occurs, despite erythromycin prophylaxis. Frequently, the infant with gonococcal conjunctivitis presents with swollen lids, purulent exudates, beefy-red conjunctiva, and conjunctival edema. The gonococcal organism can rapidly penetrate the intact corneal epithelium and produce corneal perforation if recognition and treatment are delayed. When gonococcal conjunctivitis is suspected, referral to an ophthalmologist is critical. Patients may also have systemic involvement, with associated central nervous system (CNS) signs. Both parents should be examined for venereal disease and treated, if necessary.

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

The most common gram-positive bacteria that are causative agents of conjunctivitis include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and group A and B streptococci (Fig. 41-3). Gram-negative organisms include Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bacterial conjunctivitis can occur at any age from the first day of life. Chemosis (edema of bulbar conjunctiva), purulent discharge, lid edema, and injection are common signs. Associated systemic septicemia can occur, especially with Pseudomonas infection. Cultures should be prepared on blood and chocolate agar.

Acute Dacryocystitis

Neonates may present with acute dacryocystitis, an inflammation of the lacrimal sac (Fig. 41-4). Pain, tearing, redness, and discharge usually occur. If the child is febrile, culture testing and Gram staining should be done. S. pneumoniae and S. aureus are the most common pathogens. Systemic antibiotics are indicated for the acute stage. The ophthalmologist should be consulted immediately, because irrigation and probing may be necessary to establish drainage as quickly as possible. Severe cases may progress to a dacryocystocele, sepsis, meningitis, or even death, especially in young infants.

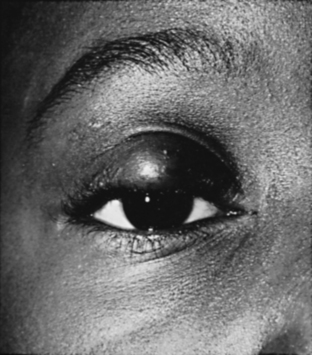

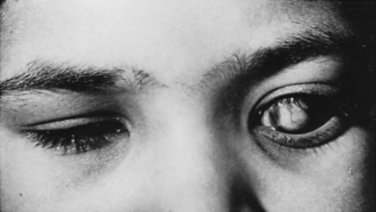

Congenital Glaucoma

Congenital glaucoma is a potentially blinding condition with an incidence of 1 per 10,000 births. It is often confused with chronic dacryocystitis. About two thirds of these cases are bilateral. These patients, similar to those with dacryocystitis, present with excessive tearing. The infants usually are light sensitive (photophobic) and frequently bury their head in a pillow or blanket. These infants often have intense blinking or lid spasm (blepharospasm). An enlarged cornea or corneal clouding can be detected clinically and measured with a plastic ruler (normal, ≤12 mm) (Fig. 41-5). Corneal edema is the result of elevated IOP, which causes breaks in the inner corneal layers (Descemet’s membrane) and intrusion of anterior chamber fluid into the corneal stroma. Increased IOP causes significant optic nerve damage, which can lead to blindness. Whenever glaucoma is suspected, immediate consultation is indicated. Surgical treatment of congenital glaucoma is successful in approximately 90% of cases. These patients must be followed by an ophthalmologist for life as a precaution against recurrent IOP elevation and amblyopia.

KEY TREATMENT

Red Eye in Adults and Older Children

Blepharitis

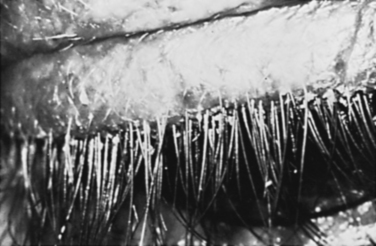

Blepharitis is a chronic lid inflammation that involves abnormalities of the glands surrounding the eyelashes. The two most common types are chronic staphylococcal infections of the lid and seborrheic blepharitis (Fig. 41-6). Staphylococcal blepharitis is the most common inflammation of the external eye. It is frequently asymptomatic initially, but as the disease progresses, the patient complains of foreign body sensation, matting of the lashes, and burning. Lid crusting, discharge, redness, and loss of lashes are observed. Seborrheic blepharitis is associated with seborrhea of the scalp, lashes, eyebrows, and ears, characterized by greasy, dandruff-like scales on the lashes. Blepharitis is not associated with skin ulcerations. Treatment of both these conditions is long and laborious. Lid hygiene is recommended for both conditions. Topical antibiotics are prescribed for staphylococcal blepharitis. Both conditions are recurrent and require repeated therapy.

Stye

A stye is the most common localized infection of one of the glands of the eyelid margin (Fig. 41-7). It is an acute boil-like lesion, and the patient usually has a swollen, tender, red eyelid. There may be a moderate amount of conjunctival injection. Treatment includes warm compresses for 15 minutes four times per day and topical antibiotics. Systemic antibiotics are usually not indicated unless there is a preseptal cellulitis component. Generally, the stye drains spontaneously within several days. If resolution does not occur within 2 weeks, the patient should be referred.

Chalazion

A chalazion is a chronic swelling of the eyelids not associated with conjunctivitis (Fig. 41-8). The chalazion, a granulomatous inflammatory reaction, may persist for weeks or even months. Chalazia are generally not amenable to oral or topical antibiotics, unless the lesion is secondarily infected. Chalazia are usually rubbery, cystic, and nontender on palpation. When the upper lid is involved, vision may be temporarily blurred. If the chalazion persists for more than 4 to 6 weeks, it may require incision and curettage. Recurrent chalazia may be caused by an underlying sebaceous carcinoma, so the lesion should be biopsied and sent for pathologic testing.

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

All common bacteria may cause acute conjunctivitis. Presently, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa are the most common pathogens. The most frequent causes of hyperacute conjunctivitis are N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis. Risk factors for bacterial conjunctivitis include contact lens wear, exposure to infectious persons, compromised immune systems, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, and sinusitis. In the presence of a severe purulent discharge, culture of the conjunctiva is mandatory (see Fig. 41-3). Subconjunctival hemorrhage may occur with bacterial conjunctivitis and is especially common with H. influenzae conjunctivitis.

In general, topical steroids should be reserved for patients under the care of an ophthalmologist.

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

A patient may present with a bright-red eye, normal vision, and no pain. Usually, no obvious cause exists, but in some patients there is a history of coughing, sneezing, or straining before the hemorrhage is present. The patient should be reassured that it is nothing more than hemorrhage of the conjunctiva. There is no therapy, except reassurance that the blood will clear within 2 to 3 weeks. Hematologic blood coagulation studies are usually of limited value in patients with subconjunctival hemorrhages unless there is a history of recurrence. Additionally, it is unusual for a hemorrhage to involve the relatively avascular sclera. If trauma is suspected, the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist to rule out more serious injuries, such as perforation, contusion, or occult rupture of the globe. Subconjunctival hemorrhage may indicate that the patient is a battered child or adult, and other signs of bodily trauma should be investigated.

Corneal Herpetic Infections

Orbital Cellulitis

Orbital cellulitis, most frequently caused by an extension of infection from the ethmoid sinus, can occur in adults and children (Fig. 41-9). It is the most common cause of exophthalmos in children. It may be difficult to differentiate a periorbital or anterior lid cellulitis from a true posterior orbital cellulitis. With a true orbital cellulitis, the child or adult has pain on movement of the eye, conjunctival edema, and limited extraocular movements. The most common causative organisms are S. aureus, Streptococcus, and H. influenzae. Cultures should be obtained from the nasopharynx, conjunctiva, and blood.

Corneal Ulcers

The most common causes of corneal ulcers include gram-positive organisms, such as staphylococci and streptococci; and gram-negative organisms, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae. Less common gram-negative organisms include Bacteroides. Risk factors for corneal ulcers include patients with corneal erosions, persistent epithelial defects, impaired immunologic mechanisms, contact lenses, chronic topical or systemic steroid use, diabetes, and alcoholism. Corneal ulcers require consultation with an ophthalmologist for appropriate culture and antibiotic therapy.

Ocular Trauma and Other Emergencies

Emergencies

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

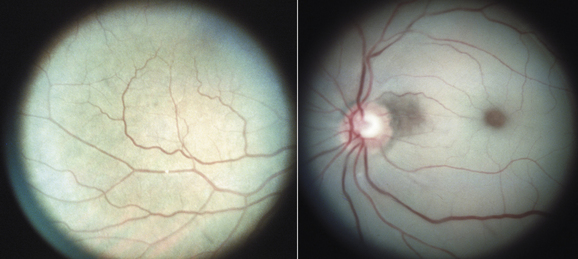

With an incidence of about 1 in 10,000 people, central retinal artery occlusion is generally not the result of trauma. Risk factors include atrial fibrillation, mitral valve disease, atherosclerosis, a hypercoagulable state, and hypertension. Additionally, prolonged intraorbital swelling can cause occlusion of the central retinal artery. Such situations occur particularly in patients who are having surgery in the face-down position. The characteristic fundus appearance with central retinal artery occlusion is narrow arterioles and a pale optic disc. In addition, there is diffuse retinal whitening. A cherry-red spot occurs only several hours after the initial retinal artery occlusion (Fig. 41-10).

Urgent Situations

Urgent situations include those for which therapy should be instituted within minutes or a few hours. They include penetrating injuries of the globe, acute angle-closure glaucoma, papillary block, orbital cellulitis, corneal ulcer, corneal foreign body, gonococcal conjunctivitis, ophthalmia neonatorum, and acute iritis. In addition, trauma with retinal tears, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and hyphemas constitute urgent situations.

Ocular Foreign Body and Other Eye Injuries

Contact Lens Overwear

Patients suffering from contact lens overwear syndrome have worn their lenses longer than usual and typically awaken during the early-morning hours with severe pain and tearing. In response to prolonged wear, the cornea becomes swollen and develops epithelial defects. Patients need reassurance that the condition is usually not serious, even though the pain is severe. However, occasional contact lens–induced corneal abrasions, especially those associated with soft lenses, can rapidly progress to severe corneal infection. Patients should be seen the next day and referred if they have not improved. Contact lens wear may be resumed only after the corneal epithelium is well healed.

Corneal and Scleral Lacerations

Corneal and scleral lacerations fall within the realm of the ophthalmologist and should be referred immediately after a shield is placed over the eye. Frequently, signs of corneal and scleral lacerations include unequal pupils, decreased IOP, iris prolapse, and hyphema, and a corneal laceration often also involves the lens. It is important to consider posterior injuries to the globe, including retinal detachment, retinal tear, and vitreous hemorrhage (Fig. 41-11). Patients can often be managed as outpatients with oral antibiotics. Intravitreal antibiotics may be given at ruptured-globe repair. Some patients are hospitalized for IV antibiotics, although current intravitreal penetration of many antibiotics is often comparable. Corneoscleral lacerations should be principally repaired at the presenting institution when possible with available ophthalmology services. Hospital transfers delay wound closure or risk wound extension or prolapse of intraocular contents.

Blunt Eye Injuries

Traumatic Hyphema

Cataract, choroidal rupture, vitreous hemorrhage, angle recession glaucoma, and retinal detachment are often associated with traumatic hyphema and compromise the final visual acuity prognosis. It is important to recognize that the prognosis for visual recovery from traumatic hyphema is directly related to three factors: (1) amount of associated damage to other ocular structures (e.g., choroidal rupture or macular scarring), (2) presence or absence of secondary hemorrhage, and (3) presence or absence of complications of glaucoma, corneal blood staining, or optic atrophy. With treatment, most hyphema patients have a good visual outcome. (See the discussion of hyphema grading and complications, as well as treatment and prognosis, online at www. expertconsult.com.)

Pediatric Ophthalmology

Evaluation of Vision within First 4 Months of Life

Evaluation of the posterior aspect of the eye, including examination of the red reflexes, may indicate an early retinal detachment or retinoblastoma. Optic nerve abnormalities may be associated with midline CNS defects, such as an absent septum pellucidum, agenesis of the corpus callosum, or hypopituitarism. Optic nerve abnormalities such as optic nerve hypoplasia are associated with nystagmus. CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify these abnormalities. Electroretinography (ERG) may be helpful for determining the cause of decreased visual acuity. An abnormal ERG is seen with Leber’s congenital amaurosis, congenital achromatopsia, and congenital stationary night blindness. Visual-evoked potential testing may be necessary to determine whether vision is intact.

Vision Screening and Ocular Examination

Four Stages of Screening

The AAO and AAPOS recommend that children be examined for eye problems in the following four stages (Table 41-4):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree