Operative Treatment of Selected Fractures of the Child’s Hand

Julie Balch Samora

Donald S. Bae

Peter M. Waters

INTRODUCTION

Children and adolescents use their hands to explore the environment, to play, and to participate in sports activities. For these reasons, fractures of the hand are common in skeletally-immature patients (1,2,3,4). While most hand fractures in children can be managed nonoperatively, a small percentage of hand injuries account for the majority of unfavorable outcomes (1,2,5,6). These fractures require careful surgical treatment to promote optimal healing, improve appearance, and prevent long-term functional compromise.

Several principles germinal to the care of skeletally-immature patients should be followed (7,8). First, unique characteristics of the physis must be understood (9). Physeal fractures constitute

approximately one-third of pediatric hand fractures (1). Although children have the advantage of bony remodeling with growth, maximal remodeling occurs in the plane of joint motion. Furthermore, the remodeling potential is greater in younger patients and in fractures located adjacent to the physis. Conversely, intra-articular injuries and coronal or rotational deformities have little remodeling potential (1,6,8). Surgical approaches and fracture fixation, when possible, should not violate the physis to avoid the complications of growth disturbance. This is typically accomplished with periosteal sutures; fine, smooth wires; or internal fixation that does not cross the growth plate.

approximately one-third of pediatric hand fractures (1). Although children have the advantage of bony remodeling with growth, maximal remodeling occurs in the plane of joint motion. Furthermore, the remodeling potential is greater in younger patients and in fractures located adjacent to the physis. Conversely, intra-articular injuries and coronal or rotational deformities have little remodeling potential (1,6,8). Surgical approaches and fracture fixation, when possible, should not violate the physis to avoid the complications of growth disturbance. This is typically accomplished with periosteal sutures; fine, smooth wires; or internal fixation that does not cross the growth plate.

The small size of structures in the child’s hand presents another challenge. Given the generous amount of subcutaneous soft tissue, deformity may be more subtle and palpation and reduction maneuvers less precise. Furthermore, the tissue available for fixation or repair is more tenuous than in adults. Smaller implants are indicated, and smooth wires are used most often in order to carefully treat the small skeletal structures and avoid physeal damage.

Finally, postoperative mobilization must be more restrictive in children, who may not comply with postoperative activity restrictions. Casts are more frequently utilized, with incorporation of adjacent fingers, the whole hand, wrist, and/or the elbow to prevent the loss of immobilization and/or secondary displacement. Postoperative stiffness is not as prevalent as in adults, and with proper surgical techniques, fracture nonunion is rare.

Rather than provide a comprehensive review of pediatric hand fractures, this chapter will focus on four specific injuries in the skeletally-immature hand requiring surgical treatment. Emphasis will be placed on surgical technique, postoperative care, and the avoidance of complications. Throughout the discussion, underlying principles of fracture care in the pediatric patient population will be highlighted.

SALTER-HARRIS III FRACTURE OF THE PROXIMAL PHALANX OF THE THUMB

Indications/Contraindications

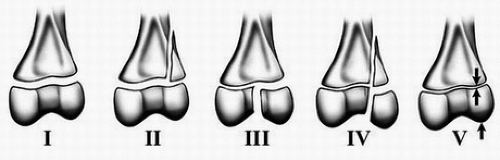

Salter-Harris III fractures are intra-articular and usually not amenable to closed reduction (Fig. 32-1). Salter-Harris III fractures of the proximal phalanx of the thumb represent the pediatric equivalent of the adult “gamekeeper’s thumb” (6,10,11,12). Given the strength of the ulnar collateral ligament relative to the physis, a radially directed force to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint will typically result in an avulsion fracture of the proximal phalangeal epiphysis (11). Displaced Salter-Harris III fractures of the proximal phalanx of the thumb require open reduction and internal fixation to restore articular congruity, joint stability, and physeal alignment (6).

Preoperative Preparation

Patients and/or parents will describe a radially directed force imparted to the thumb, typically during sports participation or a fall. Physical examination reveals tenderness and swelling at the ulnar base of the proximal phalanx. Laxity with careful radial stress may be elicited. Gentle examination techniques are required in the acute setting, particularly in the younger, anxious child. Plain anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the thumb will confirm the diagnosis. In cases in which there is laxity with radial stress and negative radiographs, one can conclude that there has been an injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb MCP joint. MRI scan should be confirmatory.

Technique

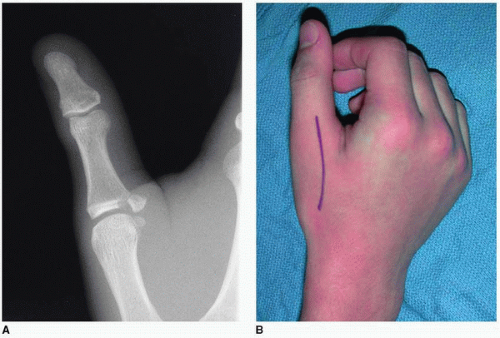

Patients are positioned supine with the affected extremity placed on a radiolucent hand table (Fig. 32-2). A well-padded tourniquet is placed on the upper brachium, and the entire extremity is prepped and draped after the induction of general anesthesia. Regional anesthesia may be utilized as appropriate. The limb is exsanguinated with an Esmarch bandage, and the tourniquet is raised to

250 mm Hg. An incision is made over the dorsal-ulnar aspect of the thumb MCP joint (Fig. 32-3). Subcutaneous dissection is performed in line with the skin incision, protecting the radial sensory nerve. The adductor pollicis fascia is released from its insertion on the extensor tendon. As the ulnar collateral ligament is usually intact, the MCP joint should be exposed distally through the fracture site. The ligament should not be divided.

250 mm Hg. An incision is made over the dorsal-ulnar aspect of the thumb MCP joint (Fig. 32-3). Subcutaneous dissection is performed in line with the skin incision, protecting the radial sensory nerve. The adductor pollicis fascia is released from its insertion on the extensor tendon. As the ulnar collateral ligament is usually intact, the MCP joint should be exposed distally through the fracture site. The ligament should not be divided.

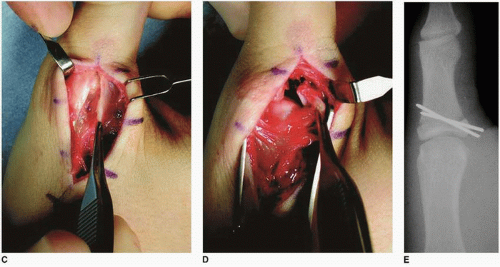

After cleaning and irrigating the fracture site, the avulsed epiphyseal fracture fragment is carefully reduced. Two parallel or slightly divergent smooth K-wires are placed into the reduced epiphyseal

fragment, across the fracture site, and into the opposite radial cortex. Intraoperative fluoroscopy is helpful to confirm anatomic reduction and appropriate placement of the wires (Fig. 32-3). If the ulnar collateral ligament is noted to be lax or avulsed, its insertion may be advanced or repaired with fine absorbable sutures to the underlying periosteum. The tourniquet is released and adequate hemostasis achieved. We prefer to bend and cut the wires superficial to the skin. A layered closure is performed, carefully reapproximating the adductor pollicis fascia. Care must be made to avoid suturing the extensor mechanism to the underlying joint capsule, which may interfere with thumb flexion. The skin is closed with 4-0 absorbable suture in a subcuticular fashion. A bulky dressing and thumb spica cast is then applied and usually bivalved.

fragment, across the fracture site, and into the opposite radial cortex. Intraoperative fluoroscopy is helpful to confirm anatomic reduction and appropriate placement of the wires (Fig. 32-3). If the ulnar collateral ligament is noted to be lax or avulsed, its insertion may be advanced or repaired with fine absorbable sutures to the underlying periosteum. The tourniquet is released and adequate hemostasis achieved. We prefer to bend and cut the wires superficial to the skin. A layered closure is performed, carefully reapproximating the adductor pollicis fascia. Care must be made to avoid suturing the extensor mechanism to the underlying joint capsule, which may interfere with thumb flexion. The skin is closed with 4-0 absorbable suture in a subcuticular fashion. A bulky dressing and thumb spica cast is then applied and usually bivalved.

Pearls and Pitfalls

If better visualization of the articular surface is necessary, the dorsal capsule may be incised.

Be certain to restore anatomic alignment to the joint and stability to the fragment.

Do not detach the UCL.

Postoperative Management

Patients remain in the thumb spica cast for 4 to 6 weeks until radiographic evidence of fracture healing. After this time, the cast is discontinued and the smooth wires are removed, usually in the office setting without the need for anesthesia. Range-of-motion and strengthening exercises are begun with a home program. A protective splint for potential traumatic activities is utilized until full motion and strength are achieved, which generally occurs by 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively. At that time, unrestricted activities are performed.

Complications

Failure of diagnosis or inadequate treatment may result in premature epiphyseal closure, nonunion, and an incongruent or unstable joint, all of which may lead to pain and limitations of strength, motion, and function (6). Angular deformity, nonunion, MCP joint instability, and posttraumatic arthrosis are risks of nonoperative treatment of a displaced fracture. In the absence of MCP joint arthrosis, nonunions may be treated with open reduction, bone grafting,

and internal fixation. Small fracture fragments may be excised with ulnar collateral ligament advancement and repair. Persistent instability secondary to ligamentous injury is treated with ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. In the setting of arthrosis, MCP joint arthrodesis may be used as a salvage procedure.

and internal fixation. Small fracture fragments may be excised with ulnar collateral ligament advancement and repair. Persistent instability secondary to ligamentous injury is treated with ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. In the setting of arthrosis, MCP joint arthrodesis may be used as a salvage procedure.

Results

With prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment using the techniques described here, patients may expect full recovery of thumb MCP range of motion and stability. To our knowledge, there have been no peer-reviewed publications reporting the results of surgical treatment of Salter-Harris III fractures of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. However, our experience with this technique has been universally successful, with patients returning to activities as tolerated.

PHALANGEAL NECK FRACTURE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree