Operative Reconstruction of the Distal Radioulnar Joint

Ronald L. Linscheid

Indications and Contraindications

Instability of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) can cause pain, weakness, snapping, and loss of forearm rotation. Instability is usually the result of a sprain or dislocation, or a healed malalignment of one of the forearm bones. It also may be noted in patients with synovitis of the DRUJ or in patients with ligamentous laxity. A few patients also seem to have excessive curvature of the distal ulna as a congenital or developmental finding. This abnormality can cause the instability, although it is more accurate to consider this as a palmar radiocarpal subluxation.

Normal forearm rotation depends on the smooth synergistic rotation of the radius about the ulna, depending on the maintenance of the normal complex curvature of the radius and ulna as well as the integrity of the proximal and DRUJ articulations (1,2). The static stability of the DRUJ is provided by the shallow concavity of the sigmoid notch, the dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments that are components of the triangular fibrocartilage (TFC), the interosseous membrane, and the dorsal retinaculum. Dynamic stability is provided by the pronator quadratus, extensor carpi ulnaris, and flexor carpi ulnaris. There is also a close interrelation of the carpus with the radioulnar joint. The carpus is tethered to the radius by the dorsal and palmar radiocarpal ligaments, and therefore rotates with the radius around the ulnar head during pronosupination.

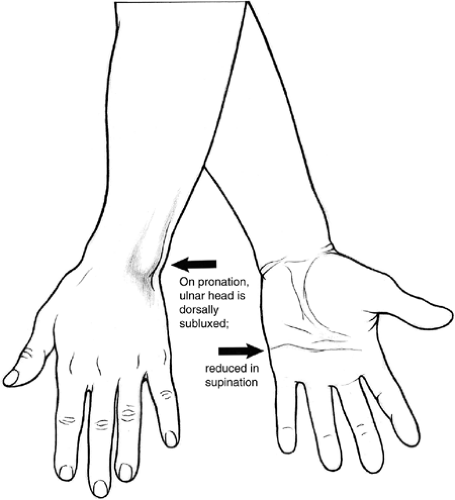

The position of the ulnar head relative to the sigmoid notch moves from the palmar to the dorsal rim as one moves from supination to pronation (Fig. 28-1). At the same time, the ulna also translates from proximal to distal. Although this latter movement is only a millimeter in distance, the combined displacement aligns the ulnar head dorsal to the proximal lunotriquetral surface in full pronation (3). Approximately 10% of the joint compressive force is transmitted to the ulnar head through the TFC. A sprain or dislocation of the ulnar head dorsally usually occurs when the forearm

is pronated. Increasing pronation, wrist extension, and radial deviation increase the tension in the dorsal radioulnar, the ulnotriquetral, and the ulnar collateral ligaments, forcing the ulnar head dorsally out of the sigmoid notch and attenuating the above restraints. In full pronation, the ulnar head is then acted on by an oblique force that tends to displace it proximodorsally. Dynamic ulnar translation of the carpus augments this mechanism.

is pronated. Increasing pronation, wrist extension, and radial deviation increase the tension in the dorsal radioulnar, the ulnotriquetral, and the ulnar collateral ligaments, forcing the ulnar head dorsally out of the sigmoid notch and attenuating the above restraints. In full pronation, the ulnar head is then acted on by an oblique force that tends to displace it proximodorsally. Dynamic ulnar translation of the carpus augments this mechanism.

Figure 28-1 Dorsoulnar subluxation and ulnocarpal dissociation are recognized most often on pronation of the forearm if the ulnar head is normal and more prominent in pronation. |

It is common for the radiocarpal complex to develop a supination deformity as the DRUJ develops dorsal instability (4). There is usually a common pathomechanical etiology. Dorsal instability of the DRUJ of this nature is the most common instability pattern. From a traumatic standpoint, it usually is induced by an energetic extension pronation loading of the wrist, such as that which occurs in a fall.

The purpose of the reconstructive technique described in this chapter is to correct both dorsal displacement of the ulnar head on the radius and supinated angulation of the carpus on the radius in cases of chronic dorsal instability. The primary indications are weakness, pain, snapping, and loss of rotation.

Contraindications to this technique include acute dorsal DRUJ instability, malalignment of either of the forearm bones, advanced degenerative changes in the DRUJ, ulnar-plus variance with evidence of ulnocarpal impingement (5), rheumatoid disease, and Ehlers–Danlos-like laxity. A relative contraindication is obvious disruption of the TFC or the base of the ulnar styloid, as this may be amenable to direct repair without augmentation.

Acute subluxation usually responds to reduction in supination and 6 weeks’ immobilization in a long-arm cast. Osseous deformities require osteotomies, realignment, length adjustment, and internal fixation. Rheumatoid deformity often can be improved by radiolunate arthrodesis, whereas ulnar head resection may accelerate instability. Collagen deficiency problems are unlikely to respond to augmentation procedures.

Preoperative Planning

Examination confirms prominence of the ulnar head as compared with the opposite wrist, particularly while the forearm is pronated (Fig. 28-2A,B). There may be an obvious, painful jerk during rotation. A positive piano key test is noted if the ulnar head is depressed and released. An even more dramatic test is to depress the ulnar head with the thumb while elevating the pisiform with the fingers (Fig. 28-2C). A crepitant relocation with a sense of relief may be experienced by the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree