Open Treatment of Multidirectional Shoulder Instability in Athletes

Ilya Voloshin MD

Kevin J. Setter MD

Louis U. Bigliani MD

History of the Technique

Multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder was originally described by Neer and Foster1 in 1980 as instability in more than one direction: anterior, posterior, or inferior. MDI is classically thought to have an atraumatic etiology; however, many patients, especially athletes, are subjected to microtrauma or even multiple frank traumatic episodes that attenuate their capsular restraints resulting in MDI. Bankart lesions and humeral head defects often associated with unidirectional traumatic instability may also be present, with less incidence, in patients with MDI.2 From an operative standpoint, it is important to distinguish MDI from unidirectional instability for two reasons: (a) standard anterior reconstructions addressing Bankart lesions and the anterior capsule alone do not address the inferior and posterior components of instability in MDI,1 (b) soft tissue imbalance created by tightening capsular structures on one side only have been shown to result in capsulorrhaphy arthropathy,2,3,4 often at a young age, caused by fixed subluxation of the humeral head in the opposite direction.4,5,6 Several reports in literature highlight the challenge of making the diagnosis of MDI.7,8 Currently, there are no specific guidelines to define this group of patients. Since the original report by Neer and Foster in 1980,1 reports of surgical treatment have utilized different criteria for assigning the diagnosis of MDI.9,10,11 A recent report by McFarland et al.12 demonstrated that the literature on this subject may be limited secondary to the variety of diagnostic criteria used to define MDI. Perhaps this has been the result of shoulder instability representing a spectrum of pathology often difficult to separate into two distinct entities—unidirectional and multidirectional. Although this distinction may be important in terms of reporting surgical results, from the surgical treatment standpoint there is a continuum of pathology that exists spanning both of these diagnostic entities.

A previously normal shoulder in an athlete can undergo adaptive capsular stretching due to sports participation (i.e., swimming or gymnastics) and subsequently undergo a traumatic episode resulting in instability in multiple directions. A study from our institution on material properties of inferior glenohumeral ligament, the main stabilizer of anterior translation of the humeral head,13 demonstrated significant strain at the midsubstance of the ligament prior to its failure.14 This is consistent with the findings in cadaveric specimens with isolated Bankart lesion, without capsular laxity, showing no increase in instability resulting in full dislocation.15 We feel that using strict guidelines for MDI versus unidirectional instability in terms of operative intervention, especially in athletes who can exhibit an overlap caused by day-to-day microtrauma with a superimposed traumatic event, can lead to potentially missing important pathology that should be addressed. The senior author (LUB) favors the anterior-inferior capsular shift operation to address the continuum of capsular and labral pathology often present in athletes.

Indications and Contraindications

Athletes with MDI may present in a variety of ways. Neer7 emphasized that the majority of his patients with this diagnosis were athletic, often exhibiting inherent ligamentous laxity who had been subjected to repetitive minor trauma or several major traumatic episodes. Participation in certain sports that expose the shoulder to repetitive microtrauma—swimming, weight lifting, gymnastics, and overhead activity sports, tends to predispose to MDI. Generalized joint laxity

is also a contributing factor in MDI even without significant trauma.1 Patients with MDI often present with shoulder and upper arm pain, fatigability, inability to carry heavy loads, and transitory numbness and weakness after activity. Often the clinical picture is not clear, however, and multiple encounters with the patient are needed to achieve the correct diagnosis.

is also a contributing factor in MDI even without significant trauma.1 Patients with MDI often present with shoulder and upper arm pain, fatigability, inability to carry heavy loads, and transitory numbness and weakness after activity. Often the clinical picture is not clear, however, and multiple encounters with the patient are needed to achieve the correct diagnosis.

A complete history of the symptoms is extremely important to determine the etiology and to elucidate the main direction of instability. Duration of symptoms, characterization of their severity, activity associated with their increase or decrease, presence or absence of the traumatic event, and history of systemic metabolic disorders resulting in generalized joint laxity should be actively sought. Instability must be separated into involuntary and voluntary. Voluntary dislocators must also be separated into patients who have positional instability and can dislocate on command and those with underlying psychiatric disorder—true voluntary instability. The patients who have positional instability and can voluntarily dislocate their shoulder when asked, but otherwise try to avoid dislocations, can have a successful result after surgical intervention after proper nonoperative management. Conversely, patients with true voluntary instability are poor surgical candidates and skillful neglect combined with nonoperative management and potentially psychiatric evaluation should be considered. The patient’s motivation for improvement should also be assessed. Strict adherence to the postoperative rehabilitation program is extremely important for a successful outcome. More than one interview is usually necessary to sort through these important issues.

A thorough physical examination must be performed to detect potential other causes of pain. It is easy to make the wrong diagnosis in a loose shoulder with other lesions, such as acromioclavicular joint arthritis or cervical radiculitis, that are responsible for pain. Many athletes’ shoulders exhibit laxity, which is normal, without the diagnosis of instability. This is a crucial point that must be remembered when examining a patient. Both shoulders as well as other joints (elbows, finger joints, and knees) must be examined for signs of generalized ligamentous laxity. Complete examination of the shoulder is crucial to determine the etiology of pain. Diagnostic injections with 1% lidocaine into the subacromial space or acromioclavicular joint are useful to differentiate subacromial pathology from glenohumeral lesions. Close inspection of scapulothoracic articulation must be performed. Any signs of muscular atrophy or scapular winging must be noted. Scapulothoracic instability may present with symptoms of vague pain and numbness and tingling similar to patients with microinstability of the glenohumeral joint. Specific tests on physical examination are useful to determine the direction of glenohumeral instability. Presence of pain during the performance of these tests is important and should be noted; however, apprehension, not pain, is a true positive result of these tests. Anterior apprehension test determines the presence of anterior instability.16 This test is performed with the arm in abduction and external rotation with the humerus being pushed forward. Posterior instability is tested with the arm flexed and internally rotated with the humerus pushed posteriorly.16 Sulcus sign is important in making the diagnosis of MDI and is indicative of inferior laxity.1 Downward pressure is applied to the adducted arm, creating an indentation of skin between the acromion and the humeral head. Inferior apprehension can be determined with the arm abducted and humerus pushed downward. Additional tests for glenohumeral instability, such as the fulcrum test, Fukuda test, relocation test, and push-pull stress test have been described and are helpful in making the diagnosis.1,2 Often a patient cannot relax enough to adequately perform instability tests in the office. Exam under anesthesia in this type of patient is a very important part of operative treatment if a nonoperative approach fails.

Plain radiographs, anteroposterior view in internal, neutral, and external rotation, scapular-Y, and axillary views are obtained to evaluate for Hill-Sachs and glenoid bony defects as well as potential other pathologic conditions. Stress radiographs can demonstrate capsular laxity, but are not usually needed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often helpful but not required to assess labral and capsular pathology. MRI with intra-articular contrast injection provides much more information about capsular redundancy and labral injuries.

An adequate course of nonoperative treatment is advised after establishing the diagnosis of MDI. Once other pathologic causes of the patient’s symptoms have been eliminated (superior labrum anterior to posterior [SLAP] tears, tendonitis, acromioclavicular [AC] joint, etc.) and the diagnosis of MDI has been made, a mandatory period of rest is necessary to allow subsidence of pain and inflammation. Once the symptoms allow, the patient is started on a guided course of physiotherapy, including rotator cuff and periscapular muscle strengthening. Based on physical finding and patient symptoms, the therapy program should be individualized to the patient’s specific needs. An adequate course of nonoperative treatment allows the surgeon to confirm the diagnosis and assess the motivation of the patient. Improper athletic technique can often be responsible for a patient’s symptoms. Strict analysis and correction of the technique combined with biofeedback and muscle retraining can often alleviate symptoms.

An adequate course of nonoperative treatment includes a period of rest and avoidance of activity causing symptoms. A course of anti-inflammatory medications may facilitate a decrease in the inflammatory process that could be part of soft tissue injury. Exercises below shoulder level are instituted to strengthen the rotator cuff musculature and deltoid. Gradual progression of the intensity and duration of the exercises allows the muscles to retrain. This is followed by progression to sport-specific exercises and gradual return to competition. If the patient has prolonged symptoms (greater than 3 months of a well controlled nonoperative protocol) that have not responded to nonoperative treatment, is motivated, and does not have true voluntary instability, operative treatment is recommended.

Surgical Technique

Pathologic instability is often a continuum between true traumatic unidirectional instability and MDI. Neer7 indicated that one of the main reasons for failure of the surgical treatment of MDI, besides making the wrong diagnosis and operating on a voluntary dislocator, is an incomplete surgical correction of all elements responsible for the instability. For this reason, the senior author (LUB) has used the anterior-inferior capsular shift for MDI, which allows excellent inspection and the ability to correct any potential type of capsular and labral pathology found at surgery. This allows the surgeon to achieve proper balance and stabilization of the glenohumeral joint, without significant loss of range of motion. A recent study from our institution analyzed normal glenohumeral joint mechanics and the mechanics following an anterior tightening procedure versus an anterior-inferior capsular shift (presented at the ASES Closed Meeting, Dana Point, Calif, 2003). Anterior tightening adversely affected joint mechanics by decreasing joint stability (instability in posterior direction), limiting both external rotation and forward elevation, and increasing joint reaction forces. The anterior-inferior capsular shift improved joint stability while preserving external rotation with slight loss of maximum elevation. The anterior-inferior capsular shift more closely re-creates normal joint mechanics when compared to isolated anterior tightening. This operation allows the surgeon to precisely titrate the reduction of the capsular volume on all sides of the glenohumeral joint by proper tensioning, overlapping, and plicating the capsule in the areas that are redundant. This can be accomplished from the anterior approach even in patients with posterior instability as a primary component of MDI.

Examination under Anesthesia

Muscle guarding can prevent adequate instability testing in the unanesthetized patient. A thorough examination under anesthesia is critical. True laxity of the shoulder can be determined at this time. This exam can either confirm the previous findings in the office or pinpoint an additional direction of laxity. Usually the directions of instability have been determined preoperatively after complete workup. Some axial pressure should be applied to the humerus to appreciate translations of the humeral head over the glenoid rim. Experience and practice is important in this technique to understand the position of the humeral head relative to the glenoid during testing.

Positioning

Interscalene block is administered and supplemented with local subcutaneous tissue injection of Marcaine in the medial axillary region. The patient is placed in a beach chair position and all the bony prominences and neurovascular structures are well padded. The patient’s head is secured to prevent hyperflexion, hyperextension, or lateral bending of the neck. The patient’s upper extremity is prepped and draped from the sternum, neck, and the medial border of the scapula. Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics are administered prior to incision.

Incision

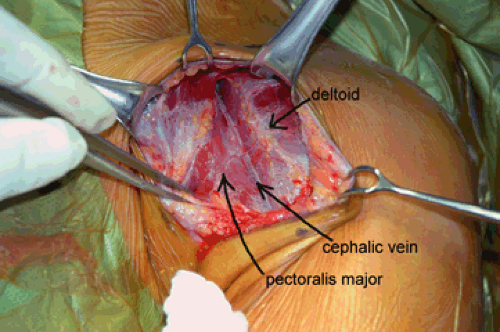

A concealed axillary incision beginning approximately 3 cm inferior to the coracoid and extending inferiorly 7 cm into the axillary crease is used (Fig. 3-1). Full thickness subcutaneous skin flaps are developed allowing exposure to the clavicle. The deltopectoral interval is identified (Fig. 3-2). Blunt dissection and electrocautery are used to separate the clavicular portion of the pectoralis major and the deltoid muscles. Most often, the cephalic vein is retracted laterally with the deltoid, as it has less contributories from the medial side. Although not routine, if warranted for lack of exposure, the upper 0.5 to 1 cm of the pectoralis major may be released from the humeral insertion while protecting the biceps tendon, which

lies deep to the pectoralis tendon. This is tagged and anatomically repaired at the end of the procedure.

lies deep to the pectoralis tendon. This is tagged and anatomically repaired at the end of the procedure.

Fig. 3-2. Identification of the deltopectoral interval.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|