Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Bicondylar Plateau Fractures

William M. Ricci

DEFINITION

Bicondylar tibial plateau fractures involve both medial and lateral tibia plateaus.

Schatzker type V and type VI fractures are both considered bicondylar fractures.

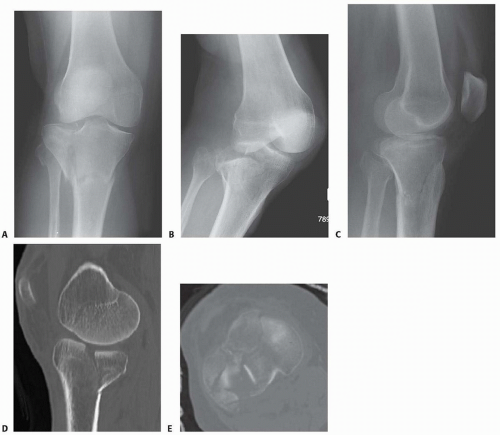

Schatzker type V fractures (FIG 1A,B) involve both condyles without complete dissociation from the shaft and are usually amenable to medial and lateral buttress plate fixation.

Schatzker type VI fractures (FIG 1C,D) involve both condyles with complete dissociation of the articular segment from the shaft. These fractures are typically treated with lateral locked plates or dual (lateral and medial) plating.

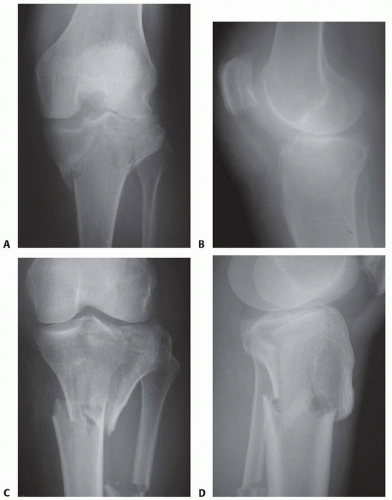

Lateral fractures with associated posteromedial fragments should be distinguished from other bicondylar types, as they often require posteromedial fixation independent from lateral fixation and may be representative of fracture-dislocation (see FIG 3).

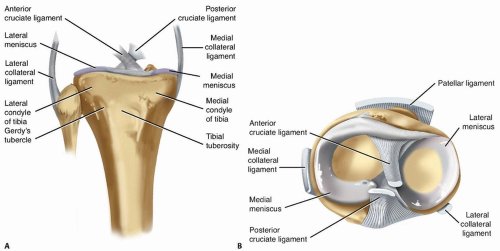

ANATOMY OF THE PROXIMAL TIBIA

The medial plateau is larger than the lateral plateau.

The medial plateau is concave, the lateral plateau convex.

Stronger, denser subchondral bone is found on the medial side due to increased load.

The lateral plateau is higher than the medial plateau. The medial proximal tibial angle is 87 degrees relative to the anatomic axis of the tibia (range 85 to 90 degrees).6

The proximal posterior tibial angle is 81 degrees relative to anatomic axis of the tibia (range 77 to 84 degrees).6

The iliotibial band inserts on the tubercle of Gerdy (FIG 2).

The anterior cruciate ligament attaches adjacent and medial to the tibial eminence. It acts to resist anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur. Recognizing a fracture fragment that contains this attachment can be important to reestablish stability to the knee.

The posterior cruciate ligament attaches about 1 cm below the joint line on the posterior ridge of the tibial plateau and a few millimeters lateral to the tibial tubercle.

The function of the posterior cruciate is to resist posterior tibial translation of the tibia relative to the femur. This acts as the central pivot of the knee.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) originates on the medial femoral epicondyle and inserts on the medial tibial condyle.

The MCL resists valgus force.

The lateral collateral ligament originates on the lateral epicondyle of the femur and attaches to the fibular head.

The lateral collateral ligament resists varus force and external rotation of the femur.

The menisci, medial and lateral, are crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structures that act to dissipate the load on the tibial plateau, deepen the articular surfaces of the plateau, and help lubricate and provide nutrition to the knee.

The medial meniscus is more C-shaped and the lateral meniscus is more circular in shape.

The lateral meniscus is more mobile than the medial meniscus.

PATHOGENESIS

Bicondylar tibial plateau fractures are typically caused by a high-energy mechanism with associated injury to surrounding soft tissue.

The mechanism responsible for injury is primarily an axial force, which may be associated with a varus or valgus moment.

With a valgus force, the lateral femoral condyle is driven wedge-like into the underlying lateral tibial plateau.5

The size of the fracture fragments depends on multiple factors, including localization of the impact, the magnitude of the axial force producing the fracture, the density of the bone, and the position of the knee joint at the moment of trauma.

Repair of ligament injuries at the time of fracture fixation is controversial. Some advocate ligamentous repair at the time of fracture fixation, whereas others feel that if the fracture can be reduced, there is no need for early ligamentous repair.

NATURAL HISTORY

Limb malalignment may predispose to adverse outcomes.

Joint incongruity can predispose to arthrosis.

Inadequate fracture stability can lead to varus-valgus collapse, usually varus.

Joint stiffness is common.

Joint instability can result from associated ligament injury.

Acute compartment syndrome is not infrequently associated.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Generally, a bicondylar injury pattern is caused by a highenergy mechanism. It may also be seen with a low-energy mechanism, such as a fall from standing height in an older patient with osteoporosis.

The patient will complain of a painful swollen knee and will have difficulty bearing weight on the extremity. Hemarthrosis will be present if the capsule has not been disrupted.

The patient history should include details of the injury mechanism, preinjury ambulatory status, and any previous injury and disability.

FIG 1 • A,B. AP and lateral views of a Schatzker type V bicondylar tibial plateau fracture. C,D. AP and lateral views of a Schatzker type VI bicondylar tibial plateau fracture.

A complete examination is required to rule out other injuries. The vascular status of the limb proximal and distal to the injury requires evaluation.

If there is an abnormality on palpation of pulses, a vascular consult may be needed.

The ankle-brachial index of the extremity, along with ultrasound examination of the leg, can be helpful in fully evaluating the possibility of vascular injury, which occurs in about 2% of these fractures.1, 9

The patient is evaluated for compartment syndrome by palpating the lower extremity compartment for swelling and passively extending the muscles in the lower extremity, noting any increase in pain.

The strength of dorsiflexion and eversion will help evaluate the peroneal nerve. It is important to examine and document peroneal nerve function before surgery because of the possibility of injury from stretch or direct impact. Motor and sensory function of the nerve proximal and distal to the injury should be assessed.

A thorough examination of the knee ligaments and extensor mechanism is needed, although this can be difficult preoperatively owing to difficulty differentiating ligamentous from bony instability.

Examination of the knee ligaments and extensor mechanism should therefore take place after operative stabilization and before the patient is awake in the operating room.

Soft tissues need careful inspection before definitive surgical intervention can take place. The surgeon should note where surgical incisions will be located when evaluating the soft tissue.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the knee and tibia and oblique views of the knee (FIG 3A-C)

Computed tomography (CT) scan with sagittal and coronal reconstruction is helpful to define complex fracture patterns and to plan surgical tactics (FIG 3D,E).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in evaluating ligament and meniscal injury around the knee.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Multiligament injury at the knee

Proximal tibial shaft fracture

Unicondylar tibia fracture

Patella fracture

Extensor mechanism disruption

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree