Chapter 40 Open Debridement and Interposition

Introduction

The many causes

Degenerative conditions of the elbow have a broad spectrum of pathology: primary osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthropathies, posttraumatic arthritis, osteochondritis dissecans and degenerative changes from instability. Furthermore conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis have their own spectrum of pathology – those who mainly present with deranged mechanics and those patients whose primary complaint is pain.1 Published results rarely discriminate between these causes, so there is limited evidence as to which are best treated with open debridement. Moreover, knowing the aetiology of the arthropathy does not predict the exact cause of the pain and stiffness. Degenerative changes of the bone or soft tissues affect any part of the complex elbow joint, so it is better to determine the anatomical cause of the patient’s pain and stiffness. Only then can it can be accurately addressed at the time of surgery.

Background/aetiology

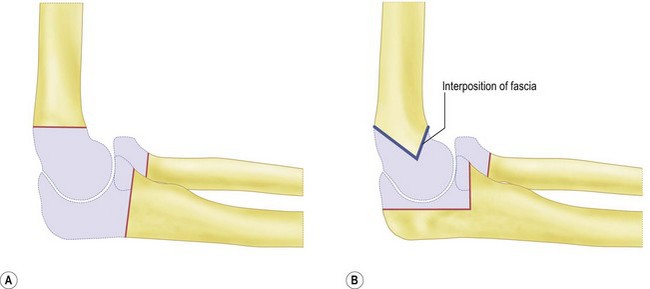

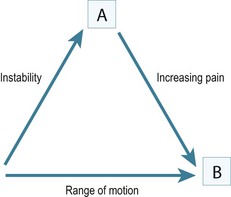

Historically the treatment for painful elbow ankylosis was a resection arthroplasty; resection of the painful joint was achieved by excising the entire olecranon, radial head and distal humerus above the condyles (Fig. 40.1A). Whilst in most cases this gave good pain relief, instability was common as there were no soft tissue or bony stabilizers remaining after surgery. Stability relied purely on the fibrous scar tissue between the cut bone surfaces. Despite this, good results were reported in posttraumatic, tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthrirtis.2–4 Defontaine introduced the interposition as a refinement to the resection arthroplasty in 1887.5 By removing less bone and leaving a fulcrum between the olecranon and the distal humerus, he addressed the difficulty of instability experienced in resection arthroplasty (Fig. 40.1B). Tissue was positioned in the joint to act as a spacer, keeping the collateral ligaments functional and providing a pain-free articulation. The material used was varied and included muscle transposition, skin, fat or even pig’s bladder. Despite the use of an interposition graft, however, because less bone was excised, stiffness and even reankylosis could still be a problem. Hass cut the distal humerus into a wedge with the idea of reducing bone contact while still providing a fulcrum, however, pain, stiffness and wear of the articulation remained a persistent problem.6 Schüller first published the use of interposition in rheumatoid elbows in 1893. Hurri et al reported on 76 rheumatoid elbows and found that interposition arthroplasty provided better stability compared with the group of patients who had had a resection arthroplasty alone.3 However, their results also showed that only 40% were pain-free compared with 64% in the resection group. These were also the findings of Buzby, who concluded that patients were happier with a pain-free, flail elbow than they were with the more stable but painful interposition arthroplasty, the surgery often providing only a few degrees of extra motion.2 Even in these early reports it became clear that movement was always achieved at the expense of stability, while movement with stability resulted in less predictable pain relief (Fig. 40.2).4

In 1971, Peterson and Janes published the experience from the Mayo clinic, which identified a spectrum of pathology in the rheumatoid elbow; those with deranged mechanics and those patients whose primary complaint was pain.1 In patients whose primary complaint was pain, a limited open debridement, synovectomy with radial head excision produced better results than interposition. The use of interposition arthroplasty has declined with the increasing success of total elbow arthroplasty, which gives better pain-free range of motion and stability in the low-demand patient.

It was not until the 1970s that Minami7 and Kashiwagi8 published the first papers giving a detailed description and recommended treatment option for less severe elbow osteoarthritis. A procedure first described by Outerbridge and then published by Kashiwagi became known as the Outerbridge–Kashiwagi procedure. In 1992 this was modified by Morrey, who used a trephine to remove osteophytes encroaching on the olecranon and coronoid fossae, with elevation rather than splitting of the triceps, the so-called ulnohumeral arthroplasty.9 The column procedure approached the elbow via a lateral incision, debriding osteophytes and releasing the capsule through both anterior and posterior intervals. A more extensive debridement arthroplasty was described by Tsuge and Mizusek, which involved a formal disarticulation of the joint, with or without release of the collateral ligaments, excision of the capsule and reshaping of the radial head.10

Aetiology of pain stiffness around the elbow

Primary osteoarthritis

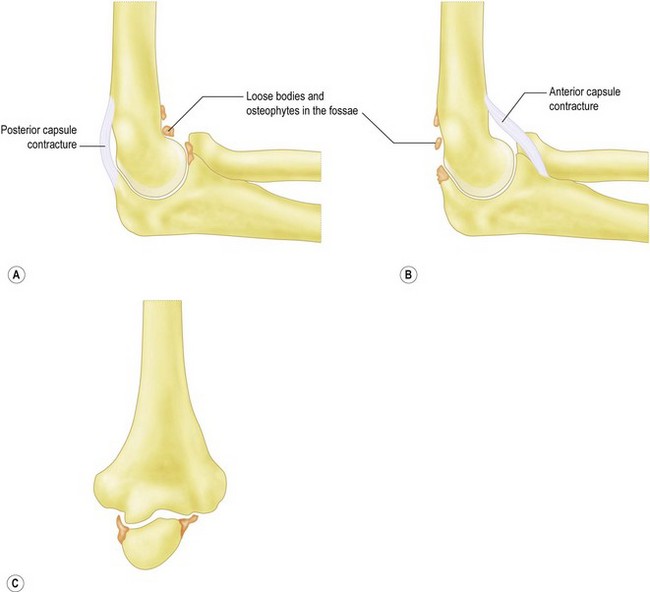

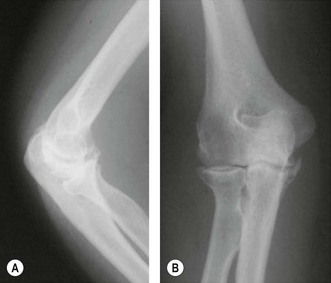

This accounts for only 2–3% of patients presenting with elbow arthritis.11 It seems to almost exclusively affect men who are engaged in repetitive heavy manual labour and is presumably as a result of a genetic predisposition, followed by environmental stimulus for wear. The pathological changes which occur as the disease process progresses have been described.12,13 The elbow forms osteophytes which occur on the coronoid, olecranon and fill their respective fossae on the humerus. Due to the high congruency of the joint, there is an early decrease in the range of movement. Pain can occur where the extra bone growth impinges on neighbouring normal bone or due to the development of a ‘kissing lesion’. The joint space, however, is initially maintained and the ulnohumeral articular cartilage is not worn.10,14,15 It is this characteristic which allows for the successful treatment with debridement of the extrinsic bone and soft tissue, leaving the relatively preserved ulnohumeral articulation alone. Osteophytes can break off and form loose bodies which cause locking as they interpose themselves within the joint. The ulnar nerve can also be irritated by the degenerative processes within the elbow and can often be a leading source of pain. Finally, ulnohumeral articular wear develops; this tends to cause pain which persists throughout the entire range of motion. Removal of osteophytes and soft tissue release will be less successful in these patients, as the ulnohumeral joint has intrinsic wear.

Heterotopic ossification

This is new bone formation within non-osseous tissues typically after elbow dislocation, with an incidence varying from 25% to 75%.12,16 This high incidence is thought to be as a result of brachialis, which is mainly muscular as it crosses the joint, being torn at the time of dislocation. It also occurs after surgery and its incidence is increased in the presence of a concomitant head injury.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

History

The patient’s age and occupation is important. Find out why the patient has consented to treatment. While most patients will complain of both pain and loss of movement, one is often more of a problem than the other. Is the loss to range of movement functionally significant? Does it stop them doing their job? If so, document whether it is flexion or extension which is the main limiting factor. This will guide you into which soft tissues or bone needs to be debrided to give the elbow a functional range of movement (Fig. 40.3). Can the patient reduce the demands on the elbow or even change jobs?

Clinical examination

Is pain limited to the endpoint of movement, suggesting impingement due to osteophytes which can be removed? Or, is it throughout the arc of movement, suggesting intra-articular wear, which is less likely to benefit from joint preserving open debridement (Fig. 40.4). Does the endpoint have a solid, bony block to it, or is it soft and springy, which would suggest a soft tissue contracture.

Trauma and instability

Accurate examination of the lateral and medial collateral ligaments is difficult; however, any gross instability should be assessed. In cases of trauma, non-union and malunion should be identified, as these may require fixation and bone grafting at surgery. In posttraumatic cases where the anatomy may have been altered, arthroscopic debridement carries a high risk of an iatrogenic injury to neurovascular structures.17

Investigation

Ultimately the decision to perform debridement is based on the disease process, anatomical culprit of the pain and stiffness, patient and surgeon factors. Table 40.1 summarizes the factors which the surgeon should consider in the management of elbow arthritis.

Table 40.1 Factors to consider prior to surgery

| Patient factors | Age |

| Activity level | |

| Willingness to modify activity level | |

| Poor rehabilitation potential | |

| Anatomical factors | Articular wear |

| Impingement spurs | |

| Loose bodies | |

| Ulna nerve symptoms | |

| Soft tissue contracture | |

| Stability | |

| Disease factors | Primary osteoarthritis |

| Inflammatory arthritis | |

| Trauma | |

| OCD in young patient | |

| Athletes | |

| Surgeon factors | Training |

| Experience | |

| Technical expertise |

Treatment options

While total joint replacement has been adopted as the treatment of choice in most other joints of the body, the role of total elbow replacement in degenerative conditions at the elbow remains limited. Kozak reported complications in four out of five elbow replacements for primary osteoarthritis at 3 years.18 In addition, elbow arthritis again largely affects middle-aged men in manual work who wish to maintain their high demands on the elbow joint; they are obviously not good candidates for arthroplasty.9

Surgical debridement serves to remove painful osteophytes which impinge causing pain and loss of movement, along with a release of soft tissues to improve movement. This is only effective in patients with relatively well-preserved ulnohumeral cartilage. If there is excessive wear and joint-space narrowing the elbow will continue to be painful and total elbow arthroplasty or interposition arthroplasty would be the better option. Various techniques to debride the elbow can now be undertaken arthroscopically. Recent advances in arthroscopic surgery to the elbow have meant many patients with less severe arthritis can be treated in this way. However, it is contraindicated in the presence of extensive osteophytes, multiple pathology, previous surgery and uncertain anatomy. While there may have been some excellent reported outcomes, arthroscopic debridement is regarded by many surgeons as having an increased risk of complications,19–23 with no clear clinical benefit over open surgery.24,25 Open debridement of the elbow remains the mainstay of treatment for moderate to severe elbow arthritis.

Contraindications for open debridement

The presence of metabolically active heterotopic ossification is a relative contraindication to early open debridement. The optimal timing for excision of the heterotopic ossification has not been established. A normal alkaline phosphatase is useful in patients who have large amounts of heterotopic ossification, typically around the hip. However, a relatively small amount of heterotopic ossification around the elbow results in only a small rise in alkaline phosphatase levels, which makes it an unreliable indicator of osteoblast activity. A three-phase technetium scan has been reported as being 90% sensitive for metabolically active heterotopic ossification and is therefore the preferred method.26 Heterotopic ossification can absorb over time, especially in children who have a recovering head injury. There is some evidence that earlier release is preferable (6 months) as it gives better long-term results.27–29 The use of preoperative radiotherapy and non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs also decreases the risk of recurrence after excision.29

Interposition arthroplasty is an option if the ulnohumeral joint has intra-articular wear and the patient is too young or active for a total elbow replacement. Interposition arthroplasty does not carry the same weight-lifting restriction as total elbow arthroplasty (5 kg lifting or 2 kg repetitive restriction) and has been shown to be durable in the active patient.30,31 Alternatives are limited in these patients; arthrodesis severely limits the functional tasks that can be performed and is poorly tolerated. Resection arthroplasty creates severe disabling instability in most patients and is only indicated in those with active infection. Satisfactory results have been published for interposition arthroplasty in healthy, active patients with severe posttraumatic or rheumatoid elbow arthrosis.30,32–35

This salvage procedure, however, should only be considered when the patient is disabled by pain with loss of function and non-operative measures have been exhausted.35 There is no age limit as a guide, but interposition arthroplasty is typically performed in patients with severe inflammatory arthritis (<30 years old) or posttraumatic arthritis (<60 years old). It is important that the elbow is stable as there is a significant association between poor outcomes and preoperative instability.30,35 For the interposition arthroplasty to have the best results there needs to be both bony congruence and soft tissue stability. The most common contraindication is insufficient bone stock which will increase postoperative instability due to lack of congruency. This can be restored by grafting the distal humerus as a staged procedure. An alternative is to use the calcaneal bone graft attached to the Achilles tendon at the time of surgery. Deformity which alters the mechanical axis of the arm will need to be corrected with an osteotomy if possible, as the pull of the flexors and extensors must be centred over the arthroplasty for stability. Ten degrees of varus or valgus is considered to be the limit. The interposition arthroplasty will not, however, provide prolonged pain-free stability if the patient is involved in very heavy manual labour which requires lifting with abduction of the shoulder. In these patients either a new occupation must be found or rarely an arthrodesis may be a better option. The sustained use of crutches or having to transfer from bed to a chair is also a relative contraindication.

The principle of the surgery is to place scar tissue between the distal humerus and olecranon in place of the articular cartilage. In 1990 Morrey developed three additional features to the technique: distraction using an external fixator, early postoperative motion and a larger interposition graft.36 Various interposition materials have been used in the ulnohumeral joint, including fascia lata,35 cutis graft,37 Achilles tendon allograft,30 Gelfoam38 and silicone.39 The Wrightington experience has been with Achilles tendon allograft, which has the benefit of no donor site morbidity and an adequate thickness without having to suture several layers together. There is some evidence that it may survive longer than fascial interposition graft, leading to fewer patients requiring revision surgery in the early postoperative period.30 The elbow is then held with a dynamic external fixator which is used as a means of initiating early motion while neutralizing forces and thus protecting the soft tissues, the interposed graft, and any ligament repair or reconstruction.31,36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree