CHAPTER 4 Open and arthroscopic instrumentation for instability repair

Appropriate anesthesia, operating room setup, and instrumentation enable the surgeon to effectively manage capsulolabral pathology using both open and arthroscopic techniques.

Appropriate anesthesia, operating room setup, and instrumentation enable the surgeon to effectively manage capsulolabral pathology using both open and arthroscopic techniques. A combination of regional and general anesthesia reduces the need for inhalational agents and assists with postoperative pain control.

A combination of regional and general anesthesia reduces the need for inhalational agents and assists with postoperative pain control. The findings of a proper examination under anesthesia before patient positioning can support the preoperative diagnosis and the planned operative approach.

The findings of a proper examination under anesthesia before patient positioning can support the preoperative diagnosis and the planned operative approach. During arthroscopic stabilization procedures, a thorough knowledge of both standard and accessory portals provides the surgeon with 360 degree access to the glenohumeral joint.

During arthroscopic stabilization procedures, a thorough knowledge of both standard and accessory portals provides the surgeon with 360 degree access to the glenohumeral joint. Some surgeons prefer open stabilization for patients participating in contact sports, those with glenoid or humeral head bone defects that require concomitant treatment, humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments, and those who have failed prior arthroscopic stabilization.

Some surgeons prefer open stabilization for patients participating in contact sports, those with glenoid or humeral head bone defects that require concomitant treatment, humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments, and those who have failed prior arthroscopic stabilization.Introduction

Management of glenohumeral instability is a common, complex problem with a spectrum of pathology ranging from acute, traumatic dislocation to atraumatic, multidirectional instability. In most cases, once nonoperative management fails to resolve the patient’s symptoms, surgical stabilization is indicated.1,2 Both open and arthroscopic techniques have been used with success in the surgical treatment of symptomatic glenohumeral instability. For each operative approach, proper patient positioning, surgical technique, and instrumentation are paramount to enable the surgeon to effectively manage various types of pathology involving the bone, tendon, labrum, and capsule. This chapter reviews these elements, providing an overview of the preparation and operative setup for open and arthroscopic shoulder stabilization.

Anesthesia

Both open and arthroscopic stabilization procedures can be performed under general anesthesia, regional anesthesia (interscalene block; Fig. 4-1), or a combined approach. The choice is based on patient preference, the anesthesiologist, the surgeon, and planned patient positioning. A combination of general and regional anesthesia has the benefits of reducing the need for inhalational agents, helping maintain the mean arterial pressure between 70 and 90 mm Hg for intraoperative visualization, and assisting with postoperative pain control. Additionally, it obviates the worry of the difficulty associated with the intraoperative conversion to general anesthesia with the patient in the lateral decubitus or beach chair position, which may become necessary.

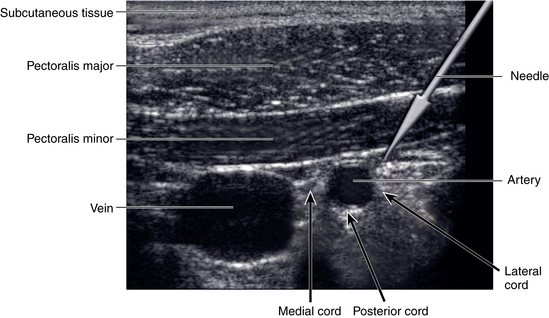

Regional anesthesia via an interscalene technique allows for the successful neural blockade of the upper extremity, including the supraclavicular, suprascapular, axillary, and radial nerves during shoulder surgery. Successful placement of the block is highly technique dependent and the anesthesiologist may employ a nerve stimulator or ultrasound to help accurately localize the placement of the local anesthetic solution (Fig. 4-2). Although the exact combination of local anesthetics varies depending on the anesthesiologist, institution, and anticipated duration of the surgical procedure, the interscalene technique has been found to be an effective method of regional anesthesia for shoulder surgery. Brown et al compared interscalene block to general anesthesia for use in shoulder surgery and found that interscalene block was safe and effective, provided excellent intraoperative analgesia and muscular relaxation, and resulted in fewer postoperative side effects and hospital admissions.3 Limited potential complications of the interscalene block include injection-associated brachial plexopathy, peripheral neuropathy, pneumothorax, and cardiac arrhythmias.4 Recent studies of regional anesthesia for shoulder surgery have reported complication rates ranging from 1.1% to 3.7%.4–6

Examination under anesthesia

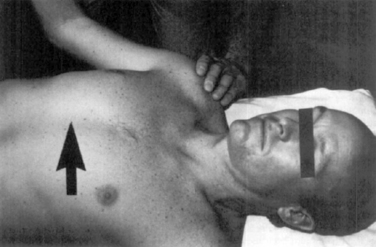

With the patient supine on the operating room table, before positioning, an examination under anesthesia (EUA) is performed on both shoulders, allowing for an assessment of range of motion and stability (Fig. 4-3). The findings of the EUA can help support the preoperative diagnosis and the planned operative approach.7,8 Range of motion is assessed by bringing each shoulder into maximal forward flexion and internally and externally rotating the shoulder with the arm both at the side and at 90 degrees of abduction. Anterior and posterior translation of the humeral head on the glenoid can be evaluated with a load-shift test, in which the shoulder is abducted to 60 degrees in neutral rotation, and an axial load combined with anterior or posterior translation force is applied to the proximal humerus.9,10 The observed translation is recorded and compared to the opposite side. The amount of humeral head translation during these provocative maneuvers can be graded on a three-grade scale (Table 4-1).11 Grade I translation is one in which the humeral head translates to but not over the glenoid rim. Grade II instability describes translation of the humeral head over the rim of the glenoid followed by spontaneous reduction when the load is removed. Translation of the humeral head over the glenoid rim, which becomes locked and irreducible denotes Grade III instability.

Table 4-1 Three-grade Scale for Anterior and Posterior Translation of the Humeral Head on the Glenoid During the Examination Under Anesthesia

| Grade | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| I | Humeral head translates to, but not over, the glenoid rim |

| II | Humeral head translates over the glenoid rim |

| III | Humeral head translates over the glenoid rim and becomes locked and irreducible |

Posterior stability can be further assessed by forward flexing the shoulder to 140 degrees, which allows the greater tuberosity to clear the acromion, and adducting to 15 degrees as a posteriorly directed force is applied. Finally, an inferiorly directed force on the humerus can be applied to assess for the presence of a sulcus sign. Given that the rotator interval tightens normally in external rotation, the sulcus sign should be performed in both the neutral position and in external rotation to evaluate for pathologic laxity. In all cases, shoulder translation in all quadrants should be compared to the opposite extremity, which may provide further insight into the normal state for an individual patient.

Pearls of Anesthesia and the Examination Under Anesthesia

Arthroscopic shoulder stabilization

As techniques and instrumentation have evolved and surgical experience has increased, the arthroscopic management of glenohumeral instability has expanded. Compared to traditional open techniques, arthroscopic shoulder stabilization allows for smaller incisions; decreased soft-tissue dissection; improved visualization of glenohumeral anatomy and pathoanatomy; reduced perioperative morbidity and postoperative pain; and perhaps, easier postoperative rehabilitation.9,12 Recent studies have demonstrated that the arthroscopic treatment of instability has clinical outcomes that are equivalent to open repairs.9,13–18

Patient positioning

Positioning in the beach chair and lateral decubitus positions for arthroscopic shoulder surgery is described in Chapter 3. Please refer to Chapter 3 for further details.

Arthroscopy equipment setup

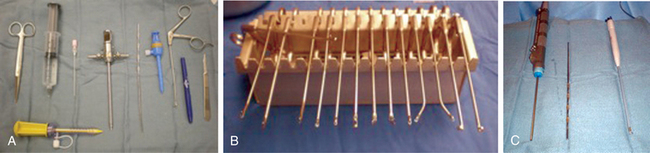

Once the patient is prepped, positioned, and draped, the necessary equipment for the arthroscopic procedure is set up (Fig. 4-4). The arthroscopic tower containing the monitor, light source, control box, and shaver power source is positioned on the side opposite to the operative site. The fluid irrigation pump and the control box for the radiofrequency device also are placed on the opposite side of the patient. A Mayo stand is positioned distally, above the patient’s waist, serving to hold the instrumentation that will be used frequently during the operative procedure. Finally, the surgical scrub technician’s back table is positioned behind the surgeon and his or her assistant for easy access.

Skin marking and portal placement

Following patient positioning and prepping of the surgical field, the superficial bony shoulder anatomy is marked out with a surgical marking pen, helping to guide the later placement of arthroscopic portals. Important anatomic landmarks to identify include the coracoid process, clavicle, acromioclavicular joint, and outline of the acromion process, paying close attention to the anterolateral and posterolateral corners of the acromion (Fig. 4-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree