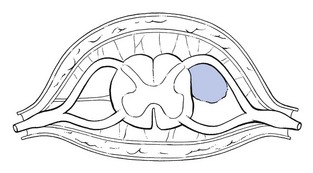

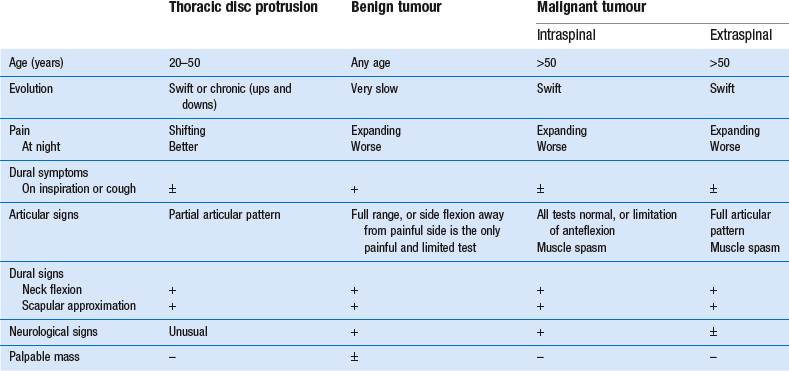

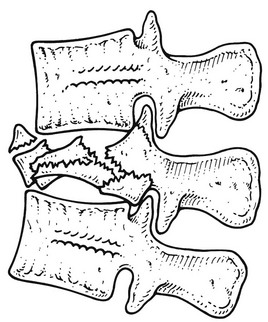

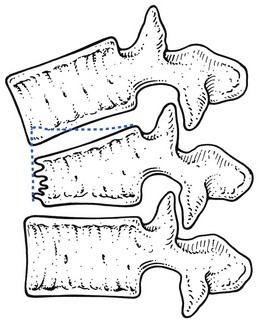

• Intraspinal tumours are sited in the spinal canal. They are further divided into intra- and extradural tumours. The former may be intra- or extramedullary. • Extraspinal tumours involve the bony parts of the vertebrae. Benign tumours are usually located in the posterior parts (spinous and transverse processes), malignant tumours in the vertebral body. This benign tumour usually originates from the dorsal root and arises from proliferating nerve fibres, fibroblasts and Schwann cells. Sensory or motor fibres may be involved.1 Some confusion exists about the terminology: various names, such as neurofibroma, neurinoma, neurilemmoma or schwannoma have been used. Some believe that all these terms cover the same type of tumour; others distinguish some slight histological differences between them. Multiple tumours in nerve fibres and the subcutaneous tissues, often accompanied by patchy café au lait pigmentation, constitute the syndrome known as von Recklinghausen’s disease. Neuromas are the most common primary tumours of the spine accounting for approximately one-third of the cases. They are most often seen at the lower thoracic region and the thoracolumbar junction.2 More than half of all these lesions are intradural extramedullary (Fig 1), 25% are purely extradural, 15% are both intradural and extradural, and very rarely they are seen intramedullary.3,4 They may become symptomatic in patients at any age, but the peak incidence is around the fourth and fifth decades.5 The tumours are benign, slow-growing and remain solitary,5 well circumscribed and encapsulated. Often there is a cystic degeneration within the tumour. A tumour that is within the intervertebral foramen is often shaped like an hourglass or dumb-bell, one limb of which can give rise to a paravertebral extraspinal extension, which is sometimes palpable. Symptoms are usually due to the compression of dura, spinal cord and roots. Few symptoms are present until the tumour reaches a large mass. Cystic tumours have a high risk of causing progressive symptomatic worsening as a result of cyst expansion.6 In the early stage, the diagnosis is often difficult because neurofibromas usually give rise to symptoms almost identical to those of a disc lesion.7,8 Thoracic neuromas may even simulate a disc problem at the lumbar level.8–11 Involvement of the sensory fibres may result in a segmental band-shaped area of numbness. The tumour may also compress the spinal cord, affecting both motor and sensory elements (see p. 390). As a consequence, the patient may complain of stiffness of the legs, muscle spasms, extrasegmentally referred pins and needles, and disturbed sphincter function with loss of bowel or bladder control.10 Exceptionally Brown–Séquard syndrome occurs.5 All signs slowly and progressively increase. Finally, neurological signs may develop but they come on much later than in malignant tumours. They may consist of a band-shaped numbness related to one dermatome. The tumour may also affect motor fibres but segmental motor deficit is very difficult to detect. Once the tumour compresses the spinal cord, any of the signs of cord compression may be encountered: depression of abdominal reflexes, hyperactive patellar and Achilles tendon reflexes and sensory loss.4 MRI appears to be the most sensitive investigation for identifying these lesions. Nerve sheath tumours have equal or less signal intensity on T1-weighted images and mild to marked hyperintensity on T2-weighted images as compared to the spinal cord.12 Focal areas of even greater hyperintensity on T2-weighted images often correspond to cystic portions. Neurofibromas may undergo malignant change or produce cord compression. Therefore, they should be surgically removed. Small posteriorly or laterally sited tumours can usually be dealt with easily. Anterior neurofibromas present more problems and usually can be only partly excised.13 The primary and most universal symptom is pain, which is usually felt centrally in the back and may spread bilaterally as girdle pain.14 The pain increases progressively and is relentless, despite the patient’s attempts to limit activities. In anterior compression of the dural sac, L’hermitte’s sign is sometimes present.15 Occasionally the pain is worst at night. Although this is classically regarded as being suggestive of a tumour, it is rather rare.8,9 Straining and coughing may increase the pain as may active movement, but to a lesser degree than in mechanical disorders.9,16 The clinical pattern depends on the extent of the tumour: all tests can be completely normal or movement may be considerably limited. If the latter, anteflexion is usually involved and there is often associated muscle spasm. As a rule, in intraspinal soft tissue masses, not much is learnt from articular movements. Besides the positive articular signs, all intraspinal masses give rise sooner or later to neurological signs caused either by involvement of one or more nerve roots or by compression of the spinal cord (see p. 390). It should be noted that a tumour is not always found where it would be expected on a clinical basis. Cases have been reported where upper thoracic tumours gave rise to pain and neurological signs in the lower limb or in the lumbar area.8,9 In all instances, further investigation is called for. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid may show elevated proteins, a finding strongly suggesting a neoplasm.9 Neoplasms that are frequently associated with skeletal metastases include tumours of the breast, prostate, lung, kidney, thyroid and colon.17–20 Data from autopsy material suggest that up to 70% of patients with a primary neoplasm from one of these sources will develop pathological evidence of metastases to vertebral bodies in the thoracolumbar spine.21 Because the majority of metastases occur in the vertebral body, they may cause anterior compression of the spinal cord, either directly by tumour growth or by a pathological fracture with retropulsion of bone and disc fragments into the spinal canal.22 Finally compression of the cord can result from an intradural metastasis.23 Neoplasms located outside the spinal canal are called extraspinal tumours. In general, benign tumours are located in the posterior elements of the vertebrae and are found in patients under 30 years of age, whereas malignant tumours (both primary and metastatic) are located in the anterior components of the vertebrae and are more common after the age of 50. Myelomas and metastases are the most frequent malignancies.17 Diagnosis is made on laboratory examination and radiographic evaluation. In 95% of cases, the first symptom is local neckache or local thoracic backache, which goes on to radiate. Suspicion should arise when this occurs in patients over 50 years of age complaining for the first time of backache not preceded by trauma. The pain tends to increase in intensity progressively and to involve a larger area: expanding pain. If radicular pain is present, it is usually worse at night (Borenstein and Wiesel:1 p. 309). Differential diagnosis (see Tables 1, 2) must be careful,8,9,16, 24–29 because the majority of the signs and symptoms also occur in ordinary thoracic disc lesions. It is based mainly on clinical examination, because up to 30% of the bone mass has to be lost before metastases may become visible on radiography.30 When there is the slightest possibility that there is a tumour, manipulation should never be done and further investigations such as a bone scan must be carried out. Table 2 Differential diagnosis of thoracic disc protrusion and neurofibroma Compression of the cord by a haematoma is also a well-known, although rare, complication of spinal surgery.31 The reported frequency is between 1 and 6 per 1000 operations. Traumatic bleeding in the epidural space has also been reported after epidural injections and chiropractic manipulations.32 Non-traumatic extradural spinal haematoma is an uncommon condition often associated with a poor outcome. There seems to be an increase of the incidence, probably from the increased use of thrombolytic and anticoagulant therapy.33–35 Other causes of non-traumatic extradural spinal haematoma include vasculitis such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), spinal arteriovenous malformations and haemophilia.36,37 A spinal epidural haematoma may present acutely or subacutely over a number of days or weeks and with fluctuating symptoms. The patient usually suffers from increasing and expanding thoracic back pain, followed by progressive signs and symptoms of major neurological dysfunction secondary to cord compression.38 Conditions that may mimic an acute spinal haematoma include extradural abscess and extradural metastatic infiltration. It is important to make an early diagnosis because surgery may offer the best hope of restoring neurological function. MRI is the examination of choice and provides characteristic findings that allow a prompt diagnosis.39 The technique can also provide useful information about the age of the haematoma.40 Spinal epidural haematoma has always been considered a neurosurgical emergency. The treatment of choice is decompressive surgery as soon as possible because permanent neurological disability or death may follow if neurosurgical intervention is delayed.41,42 However, during the last decade several reports have been published showing that non-operative treatment may be successful in cases with minimal neurological deficits, despite cord compression revealed by MRI.43–45 Spinal cord herniation is a rare, although increasingly recognized, cause of spinal cord dysfunction. It has been ascribed to a dural defect, either congenital or acquired, in the anterior surface of the dural sac through which the spinal cord herniates.46,47 The number of published cases in the English language literature markedly increased after 2000. Awareness of the clinical setting and the wider use of MRI in myelopathy are considered the pertinent factors in this increase.48 The main clinical features are thoracic pain and a Brown–Séquard syndrome. Although the dura is sensitive to pain, review of the literature shows that only 48% of the patients had thoracic pain.49,50 About 73% present with Brown–Séquard syndrome51,52 (spastic paralysis on the ipsilateral side together with numbness on the contralateral side). This is probably caused by tethering of the spinal cord at the side of the herniation which results in unilateral damage of the lateral funiculus.53 Some patients have signs of only spasticity or numbness in one leg.54 MRI is the gold standard technique for diagnosis of spinal cord herniation. On sagittal MRI, typical features are ventral displacement, sharp ventral angulation of thoracic spinal cord, and enlargement of dorsal subarachnoid space.55,56 Surgery is crucial in the management of this rare entity, and duraplasty the more widely performed method.57 This may be the outcome of either congenital deformation or hypertrophy of the posterior spinal elements. Most often it occurs in association with generalized rheumatological, metabolic or orthopaedic disorders, such as achondroplasia, osteofluorosis, Scheuermann’s disease, Paget’s disease or acromegaly. It is rare in the absence of a generalized disorder.58,59 Degenerative changes in the facet joints and the intervertebral disc can diminish the volume of the spinal canal and cause cord compression.60,61 The latter is most frequently found at T11 and T12 in middle-aged people.62,63 Arterial pulses in the lower limb are normal, which largely excludes vascular problems. The radiograph is often unremarkable and myelography can be misleading. CT scan and MRI are usually required.58,62 Two differential diagnoses should be considered: • Intermittent claudication: when pseudoclaudication is present, differential diagnosis must be made from intermittent claudication caused by vascular abnormalities. In spinal stenosis, some patients have symptoms only on standing. In intermittent claudication the pain is brought on by walking and relieved on standing still; arterial pulses are usually diminished or absent. Doppler probe and arteriography may confirm the diagnosis. • Disc protrusion: in spinal stenosis all postures or movements that bring the spine into anteflexion usually relieve the pain, whereas in a disc protrusion the opposite is more usual. Moreover, in a simple disc protrusion, activity of the lower limbs has no influence on the symptoms. The normal thoracic spine is kyphotic but if the kyphosis is beyond 40°, hyperkyphosis is present.64 The condition may occur at one or more levels and may be the result of several disorders.65 Juvenile kyphosis has its clinical onset in adolescence between the ages of 14 and 18 years; for this reason the condition is sometimes known as adolescent osteochondritis. There is a slight preponderance in females.66 It develops because of a disturbance in growth in the vertebral rim epiphysis akin to osteochondritis dissecans.67 Although the exact aetiology is unknown, it is generally believed to result from an anterior endplate lesion, through which herniations of the intervertebral disc protrude into the adjacent bone (Schmorl’s nodes).68 The intervertebral disc itself becomes narrowed, mainly anteriorly. The protrusion interferes with the growth of the vertebral ring epiphysis, which finally leads to about 5° of anterior wedging of the vertebral body. Should this occur over several levels, thoracic hyperkyphosis (with the apex normally around T7–T9) results. In this event, the condition is named Scheuermann’s disease. In adolescents the disorder usually remains painless. It usually gives rise to progressive silent hyperkyphosis, with backache present only in a minority of cases.69,70 At a later age, however, there is a predisposition to thoracic pain71 (see p. e175 of this chapter). Age-related hyperkyphosis is an exaggerated anterior curvature in the thoracic spine that occurs commonly with advanced age. Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that age-related hyperkyphosis commonly affects the elderly population with estimates ranging from 20% to 40%.72 The ‘dowager hump’ is well recognized, and most clinicians and patients equate this with spinal osteoporosis and vertebral compression deformity or angulation.73 Increasing thoracic kyphosis, in particular when linked to back pain, is considered a signature of possible vertebral body compression fracture. However, approximately two-thirds of those who are most hyperkyphotic don’t have vertebral fractures.74 In the absence of vertebral compression fracture, changes in the spinal support tissues (i.e. ligaments, tendons, disk annulus and nucleus) or supporting musculature could also lead to a progressive increase in curvature.75 Apart from being a cosmetic deformity, most cases of hyperkyphosis do not cause much pain or suffering. However, in some instances they may lead to an increased risk of vertebral fractures76 or may be complicated by a thoracic postural pain syndrome (see following page). Therapy includes the treatment of the acute exacerbations (see fractures), and of a thoracic postural pain syndrome. Also pharmacological treatment of the underlying osteoporosis with calcium and vitamin D supplementation together with bisphosphonates may be indicated.77 The thoracolumbar spine is the most common site for vertebral fractures.78 In younger patients, thoracolumbar vertebral fractures are usually caused by high-energy accidents such as falls, or motor vehicle accidents; whereas in elderly patients, osteoporosis is the dominant aetiology.79 Vertebral body fractures may also occur spontaneously as the result of an underlying disorder, such as a vertebral tumour, infection, or ankylosing spondylitis. All are classified as pathological fractures.80 High-energy fractures usually arise from an axial load in combination with flexion or lateral bending. If a compression injury with a significant flexion component is the cause, a wedge-shaped deformity with considerable loss of anterior vertebral height is commonly present (Fig. 2), resulting in angular kyphosis. Lateral bending leads to lateral wedging. In some cases the whole vertebral body is shattered (burst fracture) which can lead to serious neurological complications (Fig 3). A uniformly flattened vertebral body is more indicative of a pure axial component. Vertebral compression fractures due to osteoporosis are usually wedge fractures and have a milder clinical appearance. Fig 2 Wedge compression fracture: the middle column (posterior part of the vertebral body) remains intact. Central thoracic pain and bilateral girdle pain referred to the corresponding dermatomes. Standing or walking exacerbates the pain. Unsupported sitting is also uncomfortable. There may be twinges. Lying in the supine position generally relieves some of the discomfort.81 Spinal compression fractures can also be insidious and may then produce only modest back pain early in the course of the progressive disease. This may explain the fact that only one-third of vertebral fractures are actually diagnosed, as the patient regards his back pain as a normal part of aging.82 Plain frontal and lateral radiographs are the initial imaging study obtained for a suspected compression fracture. Compression of the anterior aspect of the vertebrae results in the classic wedge-shaped vertebral body with narrowing of the anterior portion. A decrease in vertebral height of 20% or more is considered positive for compression fracture.83 Computed tomography can be used for evaluating the posterior vertebral wall integrity and for distinguishing a wedge fracture from a burst fracture. In the latter, the middle column, consisting of the posterior half of the vertebral body, the posterior longitudinal ligament and the posterior fibres of the annulus fibrosus, is disturbed, and varying degrees of retropulsion into the neutral canal takes place, provoking neurological signs (Fig. 3).84 During the last decades vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty have been promoted for the management of severe recalcitrant pain. Initially reported by Galibert et al in 1987, vertebroplasty involved the destruction of an angioma through consolidation of the vertebral column by percutaneous injection of acrylic cement;85 however, vertebroplasty is now commonly used in treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures.86 Kyphoplasty involves the use of an inflatable bone tamp that when introduced into the vertebral body, restores vertebral height and forms a space for injection of acrylic cement.87

Disorders of the thoracic spine

Pathology and treatment

Disorders and their treatment

Tumours of the thoracic spine

Intraspinal tumours

Thoracic neurofibroma

Pathology

History

Clinical examination

Special investigations

Treatment and prognosis

Other intraspinal masses

Clinical presentation

Further investigations

Extraspinal tumours

Clinical presentation

Extradural haematoma

Neurofibroma

Thoracic disc protrusion

Age

Young

20–50 years

Pain

Slowly increasing

Swift onset; if chronic, no increasing pain but ups and downs

On inspiration or cough

+

+

Preferred sleeping position

Sitting up

Lying down

Articular movements

Usually negative

Partial articular pattern

Side flexion away from the painful side: painful and limited?

Dural signs

Neck flexion

+

+

Scapular approximation

+

+

Neurological signs

Band-shaped area of numbness in one dermatome

+

Unusual

Segmental motor deficit

+

Unusual

Signs of cord compression

+

Unusual

Palpable mass

±

_

Spinal cord herniation

Thoracic spinal canal stenosis

Clinical presentation

Further investigations

Differential diagnosis

Chest deformities

Hyperkyphosis

Juvenile kyphosis

Clinical presentation

Hyperkyphotic posture in the elderly

Vertebral body fractures

Osteoporotic compression fractures