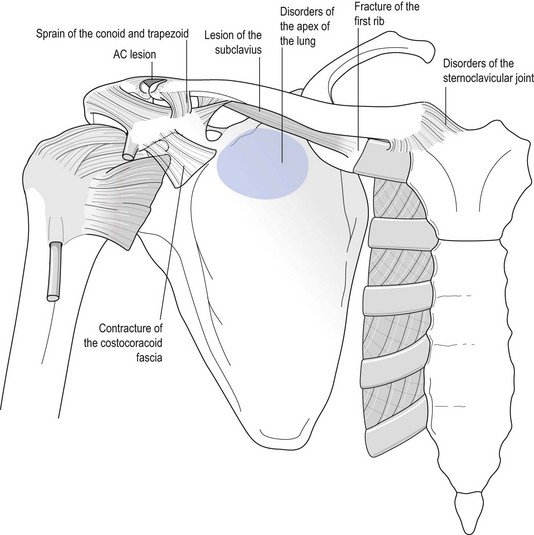

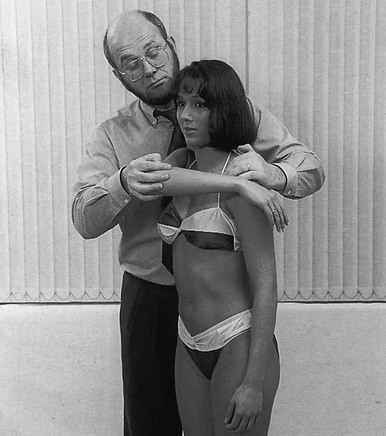

Pain on active and passive elevation Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint Sprain of the acromioclavicular joint Traction fracture of the spinous process C7 or T1 Lesion of the conoid/trapezoid ligament Pain on active elevation and protraction Painful limitation of active and passive elevation Ankylosis of the acromioclavicular joint Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint Disorders of the costocoracoid fascia Limitation of active elevation and weakness of resisted elevation Paraesthesia brought on by active and/or passive elevation Crepitus during scapular elevation Disorders of this joint are usually the result of an injury; arthrosis, hyperostosis and rheumatoid or septic arthritis are other possibilities.1 All conditions give rise to both scapular and shoulder signs and occasionally to signs on movements of the neck. The clinical pattern closely resembles that of an acromioclavicular joint lesion but the localization of pain at the medial end of the clavicle draws attention to the sternoclavicular joint. In posterior sternoclavicular syndrome, the pain is felt posteriorly at the base of the neck. Pain is also found on active and passive movements of the arm because almost all arm movements have some influence on the sternoclavicular joint. Pain is most marked on elevation of the arm. When a disorder of the sternoclavicular joint is suspected, passive horizontal adduction of the arm should be performed: pain is most pronounced with this test (Fig. 2). The patient lies supine. The gap between the medial end of the clavicle and the sternum is palpated. A needle of 2.5 cm is introduced, penetrating the joint to a depth of about 1 cm (Fig. 3), and 1 ml of triamcinolone acetonide is injected. If excessive resistance is encountered, the needle is in the meniscus; if this occurs, the tip of the needle should be partly withdrawn with continuous pressure on the plunger until the steroid floats in with little resistance. Arthrosis of the sternoclavicular joint is common.2 It occurs mainly in postmenopausal women. The chief complaint is cosmetic: there is a visible thickening of the joint. The pain, if any, is minor 3. Elevation of the arm is limited as the result of the limitation of the shoulder girdle movement. Movements of the shoulder girdle are uncomfortable but not really painful. Radiography shows degenerative changes (osteophytes, bone cysts, hyperostosis and diminution of the joint line), most pronounced at the inferior aspect of the clavicular head. Occasionally calcification is seen in the ligaments.4 Rheumatic conditions may also affect the sternoclavicular joint. This often occurs in ankylosing spondylitis.5 It gives rise to the same clinical pattern as in a sprain, but local swelling from synovial thickening is present. A progressive ankylosis develops with pronounced limitation of movement in the shoulder girdle. Other sites of rheumatoid arthritis should bring the disorder in mind, although the sternoclavicular joint may be the first joint affected. Bacterial agents such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus group B and Brucella spp. have been isolated in septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint.6,7 Septic arthritis occurs in elderly patients with a deficient immune system, with rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus, and in drug addicts.8–10 The patient usually has fever, chills and sweating, and complains of pain and swelling in the sternoclavicular area, sometimes at the base of the neck. In about 20% a local, warm and erythematous mass is present at the joint because of abscess formation.11–13 A combination of neck signs, shoulder signs and shoulder girdle signs is found on examination: • Passive and resisted neck movements are painful as the result of passive and active stretching of the sternocleidomastoid and scaleni muscles. • Active and passive elevation of the arm are very limited. • Active and passive shoulder girdle movements are painful and limited. There is warmth, swelling and exquisite tenderness over the sternoclavicular joint. Pain is usually confined to the area of the acromioclavicular joint. Both active and passive elevation of the scapula may be slightly painful but painless movement is not uncommon. The diagnosis becomes clear when the shoulder is examined. Local pain over the acromioclavicular joint is provoked at the end range of the three passive movements of the shoulder examination: passive elevation, lateral rotation and medial rotation (for a detailed description, see p. 241). Pain occurs spontaneously and is felt unilaterally at the base of the neck and in the scapulopectoroclavicular area. The clinical picture is typical. There are neck, shoulder girdle and shoulder signs. In the neck a ‘contractile tissue pattern’ is found: pain on active and passive side flexion towards the painless side, combined with pain on resisted side flexion towards the painful side. All scapular movements are more or less painful and active elevation of the arm is impossible because of the pain: the arm stops at the horizontal. Passive elevation is full but painful. Radiography is confirmative (see also p. 237).

Disorders of the inert structures

Pain on active and passive elevation (Fig. 1)

Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint

Shoulder signs

Sprain of the sternoclavicular joint/ligaments

Treatment

Technique: injection of the sternoclavicular joint

Posterior sternoclavicular syndrome

Arthrosis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Septic arthritis

Sprain of the acromioclavicular joint

Disorders of the first rib

Stress fracture of the first rib

of the inert structures