Odontogenic and Related Tumors

The jawbones are susceptible to special tumors that derive from their dental structures. These lesions simulate neoplasms of osseous derivation. The following tabulation of these special tumors, short and somewhat simplified, should be useful to the general pathologist. This short list includes most of the special lesions that the general pathologist is likely to encounter: ameloblastoma, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (Pindborg tumor), ameloblastic fibroma, ameloblastic odontoma, complex odontoma, myxoma (fibromyxoma), and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (ameloblastic adenomatoid tumor). Several years ago, the term odontogenic mixed tumor was suggested and included ameloblastic fibroma, ameloblastic odontoma, and complex and compound odontoma. This designation acknowledges that histologic overlap is seen among members of this group and suggests that they are hamartomatous malformations of the odontogenic anlage. Peculiarly, the fibrous portion of these tumors may become malignant and produce a rare odontogenic sarcoma, including ameloblastic sarcoma.

Bone tumors generally found in the other areas of the skeleton may occur in the jaws; hence, pathologists interested in bone tumors become involved with lesions of odontogenic origin and, therefore, peculiar to the jawbones.

Some special characteristics of tumors of the jaws must be recognized. Osteochondromas practically never occur in the jaws. Benign chondroblastomas and chondromyxoid fibromas in these bones are pathologic curiosities, and the few recorded cases tend to be atypical. The histopathologic features of osteoblastomas overlap those of so-called cementoblastomas (see Chapter 10). Giant cell tumors of the type found in other bones occur rarely, if ever, in the jaws, with the possible exception of those few that develop in Paget disease. Chondrogenic neoplasms of the jaws are nearly always malignant; one must be aware, however, of chondroid differentiation in a callus or in heterotopic ossification in this region. Osteosarcoma has been easier to cure when it arises in the jaws than when it arises in other skeletal sites; in these small bones, the lesion develops in somewhat older patients and shows better (and often more) chondroid differentiation. Adamantinoma of long bones is a different tumor from ameloblastoma, although histologic similarities exist.

Giant cell (reparative) granuloma is distinctively a tumor of the jaw, but a similar process occasionally affects the supramaxillary region and, on rare occasions, even bones at other sites. Aneurysmal bone cyst is probably closely related to giant cell reparative granuloma of the jaw, and a classic example is sometimes found there. Synovial chondromatosis occasionally affects the temporomandibular joint. Metastatic carcinoma can simulate a primary tumor of the jaw.

Although included in many classifications, dentinomas are probably variants of some of the above hamartoma-like tumors, such as ameloblastic odontomas. Cementifying fibroma (periapical fibrous dysplasia) derives from specialized bone around the dental roots and, thus, is not strictly odontogenic. Bulbous masses of densely ossified material surrounding dental roots are considered to be cementomas.

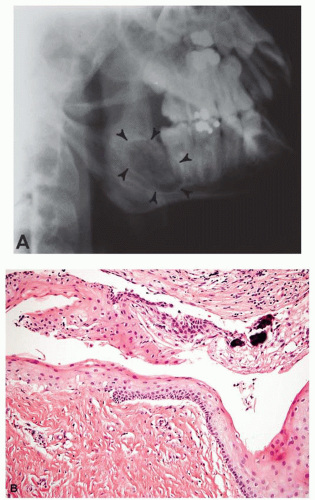

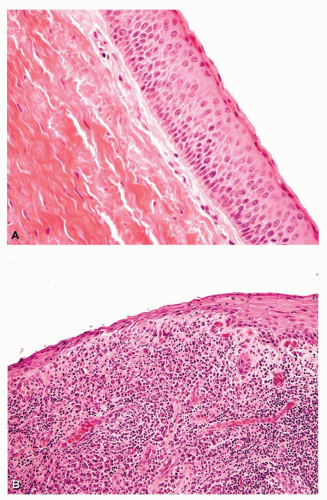

Cysts of the jaws are usually lined by squamous epithelium. Reference to the history and radiographs is necessary for determining whether these cysts are related to unerrupted teeth or to residual epithelial islands after dental extraction or whether they have some other genesis. Keratocyst has become recognized as the correct designation for a cyst of the jaw that typically has a thinner epithelial lining, lacks significant basal zone irregularity like that of rete pegs, and shows keratinization at the surface (Figs. 27.1 and 27.2). These cysts have an annoying capability to recur, are often multicentric, and may be associated with various abnormalities of basal cell nevus syndrome. These are sometimes referred to as primordial cysts. Occasionally, degenerative alteration with calcification of the epithelium produces what has been called calcifying epithelial odontogenic cyst. These cysts and the hemorrhagic or

traumatic cysts of the jaw, which have no lining, pose little diagnostic problem for the histopathologist.

traumatic cysts of the jaw, which have no lining, pose little diagnostic problem for the histopathologist.

Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws are relatively common. They have such a wide variation in the amount of osseous component that they defy strict classification (Fig. 27.3). Pathologically, the lesions fit into the general category of fibrous (fibro-osseous) dysplasias. Benign, densely collagenous, fibroblastic tissue contains a variable amount of bone that typically arises as a metaplastic change in the tissue. Occasional lesions are large expansile masses that may bulge into and destroy the sinuses, for which the term fibrous osteoma or osteofibroma is preferred by some. Most are centrally originating lesions that vary greatly in size and radiopacity. On radiographs, the lesion may be noted incidentally or may greatly distort the bone. A small proportion of the lesions are part of the polyostotic fibrous dysplasia complex. Even cherubism, with its fibrous expansion of the jaws of children, that is characteristically familial and bilateral and tends toward spontaneous resolution, is often called fibrous dysplasia. The least conspicuous end of the spectrum is periapical fibrous dysplasia. All these fibro-osseous lesions are benign, although they may recur. Conservative surgical management is indicated. Unless exposed to radiation therapy, the lesions have little tendency to malignant change. Some osteosarcomas of the jaws are so lacking in overt anaplasia that they are difficult to differentiate from fibrous dysplasia. Fibrous dysplasia and fibro-osseous lesion were the terms applied to the various members of this group by Waldron and Giansanti, who concluded that although similarities exist, the lesions generally can be separated into these two families

of diseases. Fibrous dysplasias tend to be diffuse, whereas benign fibro-osseous lesions tend to be extremely well demarcated. Benign fibro-osseous lesions also appear more active in having osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. The World Health Organization classification, although relatively elaborate, is useful because it is reliable and valid and most of the lesions encountered can be assigned to an appropriate grouping.

of diseases. Fibrous dysplasias tend to be diffuse, whereas benign fibro-osseous lesions tend to be extremely well demarcated. Benign fibro-osseous lesions also appear more active in having osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. The World Health Organization classification, although relatively elaborate, is useful because it is reliable and valid and most of the lesions encountered can be assigned to an appropriate grouping.

This chapter is not meant to supplant standard texts on this complex subject. Some of the lesions are rare; for instance, only one melanotic progonoma has been recognized in the Mayo Clinic series.

AMELOBLASTOMA

Ameloblastoma is the most common of the odontogenic tumors in the Mayo Clinic series; yet, it comprises only about 1% of the cysts and tumors seen in the region of the maxilla and mandible. There were approximately 230 ameloblastomas in the Mayo Clinic series through 2003. During this same period, there were 137 osteosarcomas that involved the jawbones.

Females predominated by a ratio of 4:3. Most patients with ameloblastoma are young adults. The youngest patient with an ameloblastoma in the Mayo Clinic files was 7 years old. Only 10 patients were in the first two decades of life. More than 60% of the patients were in the third through fifth decades of life. About 80% of the lesions arose in the mandible, most commonly in the molar-angle region (Fig. 27.4). Being slow growing, the tumor is usually painless. Swelling is the usual symptom. Radiographs typically show a coarsely trabeculated zone of osseous destruction that has the appearance of a multilobular cystic cavity (Fig. 27.5). The bone often appears to be replaced by several well-defined radiolucent areas that give the lesion a honeycomb or soap-bubble configuration. The tumor may be so predominantly cystic that a squamous epithelial-lined cyst with incidental nonneoplastic ameloblastic elements in its wall becomes a differential consideration. The histologic appearance of ameloblastoma is typical but variable. The predominant feature is the proliferation of epithelial cells with varying amounts of surrounding fibrous tissue. Some lesions are quite cellular, with little fibrous connective tissue, whereas others show widely separated epithelial islands with fibrous connective tissue. The epithelial cells characteristically have what have been termed a follicular

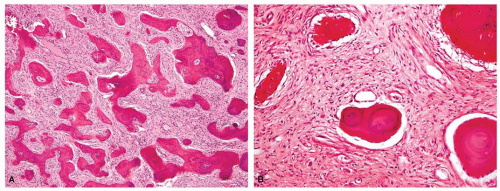

pattern, in which the epithelial cells are arranged in a palisading pattern at the periphery with central, more loosely arranged tissue suggesting a stellate reticulum (Figs. 27.6A & 27.7). The cells at the periphery are columnar and have the appearance of basal cells. They do not show any significant cytologic atypia. The term plexiform pattern is used when epithelial cells tend to form anastomosing chords (Fig. 27.6B). Occasionally, a cellular variant may resemble spindle cell sarcoma. Squamous metaplasia is relatively frequent and may be so extensive as to suggest a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. However, the squamous cells do not show cytologic atypia (Fig. 27.8

pattern, in which the epithelial cells are arranged in a palisading pattern at the periphery with central, more loosely arranged tissue suggesting a stellate reticulum (Figs. 27.6A & 27.7). The cells at the periphery are columnar and have the appearance of basal cells. They do not show any significant cytologic atypia. The term plexiform pattern is used when epithelial cells tend to form anastomosing chords (Fig. 27.6B). Occasionally, a cellular variant may resemble spindle cell sarcoma. Squamous metaplasia is relatively frequent and may be so extensive as to suggest a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. However, the squamous cells do not show cytologic atypia (Fig. 27.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree