Osteoblastoma (Giant Osteoid Osteoma)

The literature on this rare benign tumor is especially confusing. The osteoblastic nature of the tumor often results in zones similar to those of an osteoid osteoma, producing a histologic kinship that cannot be ignored. Osteoblastoma differs, however, in not sharing the markedly limited growth potential of the average osteoid osteoma. Further, osteoblastoma frequently lacks the characteristic pain and the halo of sclerotic bone associated with osteoid osteoma. Even so, occasionally a lesion has composite features that place it midway between the two lesions under discussion. McLeod and coworkers resolved this problem by arbitrarily regarding an equivocal lesion as an osteoblastoma when the lesion was more than 1.5 cm in greatest dimension.

The term giant osteoid osteoma, introduced several years ago, was an attempt to recognize the pathologic similarity of this lesion to osteoid osteoma, at the same time indicating a difference, especially in the size of the average tumor. Benign osteoblastoma nevertheless has become the most widely accepted designation for this tumor.

In the literature on neoplasms, osteoblastoma is found under various diagnoses, including giant cell tumor, osteoid osteoma, osteogenic (or ossifying) fibroma, and sarcoma. An important reason for recognizing this entity is that it commonly has been mistaken for the much more aggressive giant cell tumor or even for osteosarcoma.

One may logically question whether osteoblastoma is correctly classed with true neoplasms because some osteoblastomas regress or become arrested after incomplete surgical removal. Fields within some of these tumors resemble portions of an aneurysmal bone cyst. This resemblance, coupled with the pronounced clinical similarity, suggests that both tumors may be different manifestations of a reaction to some as yet unknown agent.

However, some osteoblastomas are locally aggressive. Osteoblastomas have even led to the death of the patient, especially when in such locations as the spine. The terms aggressive osteoblastoma and malignant osteoblastoma in the literature emphasize this problem. There are rare well-documented examples of osteoblastoma undergoing malignant change to osteosarcoma. The problem is compounded by the finding that some osteosarcomas have microscopic fields indistinguishable from those of osteoblastoma. Hence, at least some reported examples of osteosarcoma arising from an osteoblastoma may actually be examples of osteosarcomas that were underdiagnosed. These features suggest that osteoblastoma should be considered a neoplasm and not a reactive process. Perhaps the terminology should be osteoblastoma, not benign osteoblastoma, to emphasize the rare aggressive lesion.

The lesion called cementoblastoma at or around the root of a tooth is very similar, too, and has been included with osteoblastoma in this series.

INCIDENCE

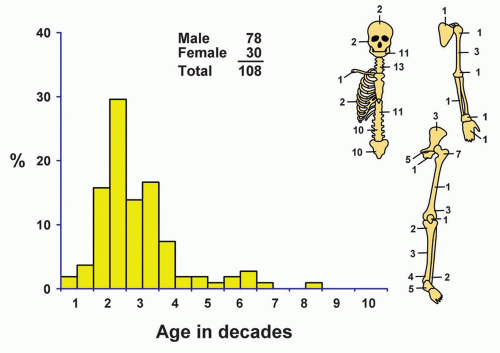

Osteoblastoma accounted for approximately 3.5% of all benign primary tumors of bone in the Mayo Clinic series and 1% of all bone neoplasms (Fig. 10.1).

SEX

Male patients accounted for approximately 72% of all cases. The marked male predominance also occurred in a large series of tumors reported by Lucas and coauthors.

AGE

The younger age group was predominantly affected, and more than 80% of the patients were in the first 3 decades of life. The youngest patient was 4 years old, and the oldest was 75.

LOCALIZATION

Osteoblastoma, in contrast to most other neoplasms of bone, has a distinct predilection for the vertebral column. The spinal column and sacrum were involved in more than 40% of all lesions. The rest were in the long bones, except for 11 in the mandible (several of these might be called cementoblastoma), 9 in the innominate bone, 2 each in the ribs and the maxilla, 5 in the tarsal bones, and 1 each in the carpals, phalanges of the hand, and clavicle.

Osteoblastomas in the vertebral column tend to involve the posterior elements. In the series reported by Lucas and coauthors, 55% of the lesions were contained entirely within the dorsal element, whereas 42% affected both the dorsal element and the adjacent vertebral body. Rarely was an osteoblastoma confined to the body of a vertebra.

SYMPTOMS

Pain, often progressive, was the most frequent complaint, identified in 87% of the patients. Local swelling, tenderness, warmth, and gait disturbances were also mentioned frequently. Ten patients had neurologic disorders secondary to spinal tumors at presentation, ranging from numbness and tingling to paraparesis and paraplegia. The average duration of symptoms was 2 years. Mirra and coauthors described a case of osteoblastoma associated with severe systemic toxicity. Symptoms included massive weight loss, chronic fever, anemia, and systemic periostitis. The symptoms abated after amputation. Yoshikawa and coauthors reported two examples of osteoblastoma associated with osteomalacia.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Physical examination is of little value in the definitive diagnosis of this lesion, but it may show a tender mass at the site of the tumor. Atrophy of the adjacent muscles sometimes occurs. Various neurologic deficits may be noted, depending on the degree of involvement of the spinal cord or emerging nerves.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

The radiographic features of osteoblastoma are often nonspecific, and the radiographs may not suggest the true diagnosis. In reviewing the radiographs of 116 cases of appendicular osteoblastoma, Lucas and coauthors found that 65% of the tumors were located within the cortex and the other 35% in the medullary canal. Included in those involving the cortex were six tumors that arose on the surface of bone. Of the 116 lesions,

42% were metaphyseal, 36% were diaphyseal, and 22% were epiphyseal. The lesions were from 1 to 11 cm in greatest dimension, with an average of 3.18 cm. Only eight lesions had a calcified central nidus with a lucent halo suggestive of the diagnosis. Reactive sclerosis was found in more than 50% of the cases. Periosteal new bone formation was also frequent. The lesions had large areas of destruction of the bone and variable sclerosis. The margins were well defined, poorly defined, or indefinite. On the basis of the radiographic features, 72% of the lesions were thought to be benign, 10% to be malignant, and the rest to be indeterminate (Figs. 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, 10.8 and 10.9).

42% were metaphyseal, 36% were diaphyseal, and 22% were epiphyseal. The lesions were from 1 to 11 cm in greatest dimension, with an average of 3.18 cm. Only eight lesions had a calcified central nidus with a lucent halo suggestive of the diagnosis. Reactive sclerosis was found in more than 50% of the cases. Periosteal new bone formation was also frequent. The lesions had large areas of destruction of the bone and variable sclerosis. The margins were well defined, poorly defined, or indefinite. On the basis of the radiographic features, 72% of the lesions were thought to be benign, 10% to be malignant, and the rest to be indeterminate (Figs. 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, 10.8 and 10.9).

There were 66 vertebral osteoblastomas in this series. Sizes ranged from 1 to 15 cm, with an average size of 3.55 cm. Margination could be good, intermediate, or poor, and each of these three types occurred with equal frequency. Osteoblastomas of the jawbones usually show heavily mineralized well-demarcated lesions at the base of a tooth.

In summary, the radiographic features of osteoblastoma may be quite specific but usually are not and may suggest malignancy.

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

Whole gross specimens are rarely seen because the average lesion is removed with curettage. The lesions are reasonably well circumscribed. The tumor tissue is hemorrhagic, granular, and friable because of its vascularity and osteoid component, which shows variable calcification. In some of the older lesions, the consistency resembles that of cancellous bone and decalcification is necessary before microscopic sections can be made. When the tumor bulges from and distorts the contour of the affected bone, the margins of the tumor are sharply defined (Figs. 10.10, 10.11 and 10.12).

As previously indicated, the bone adjacent to a benign osteoblastoma often is not sclerosed. Some of the tumors have a thin sclerotic rim, whereas others, especially those in the long bones of the extremities, have a zone of increased density as prominent as that of the ordinary osteoid osteoma.

In some tumors, the greatest dimension has extended to 10 cm. Sometimes the vascularity of the osteoblastoma is so great that hemostasis may be a problem for the surgeon.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

Osteoblastomas are composed of anastomosing bony trabeculae in a loose fibrovascular stroma. The lesion is extremely well circumscribed, and toward the edges, the trabeculae of neoplastic bone tend to merge with those of a host bone, giving rise to an appearance of maturation (Fig. 10.13).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree