Chapter 37 Nutrition and Family Medicine

Overview

Current Dietary Guidance

The latest version of the public health dietary guidance program was introduced in 2010. This is in connection with the MyPyramid food guidance system (www.MyPyramid.gov). The MyPyramid recommendations are based on the following:

The new food pyramid has an interactive interface, allowing for customization of the food plan as well as key concepts into a visual image (see Web Resources). Although there is general agreement, many argue that the recommendations are vague and that food amounts and groupings are inappropriate. The major addition in this version of the food guidance system has been physical activity, which seems to be critical in the considerations of diet and the balancing of energy needs with intake. The overarching concepts of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines (www.dietaryguidelines.gov) explain the educational framework for the MyPyramid, as follows:

Increase the amount and variety of seafood consumed by choosing seafood in place of some meat and poultry

Increase the amount and variety of seafood consumed by choosing seafood in place of some meat and poultry Replace protein foods that are higher in solid fats with choices that are lower in solid fats and calories

Replace protein foods that are higher in solid fats with choices that are lower in solid fats and caloriesNutrition Assessment

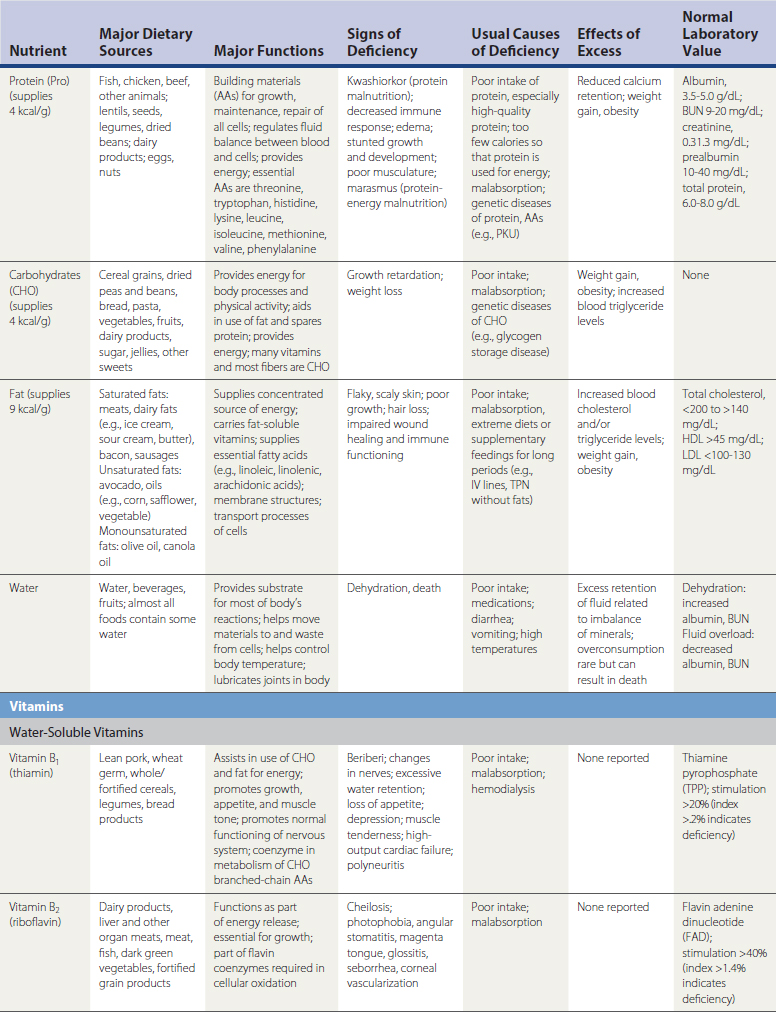

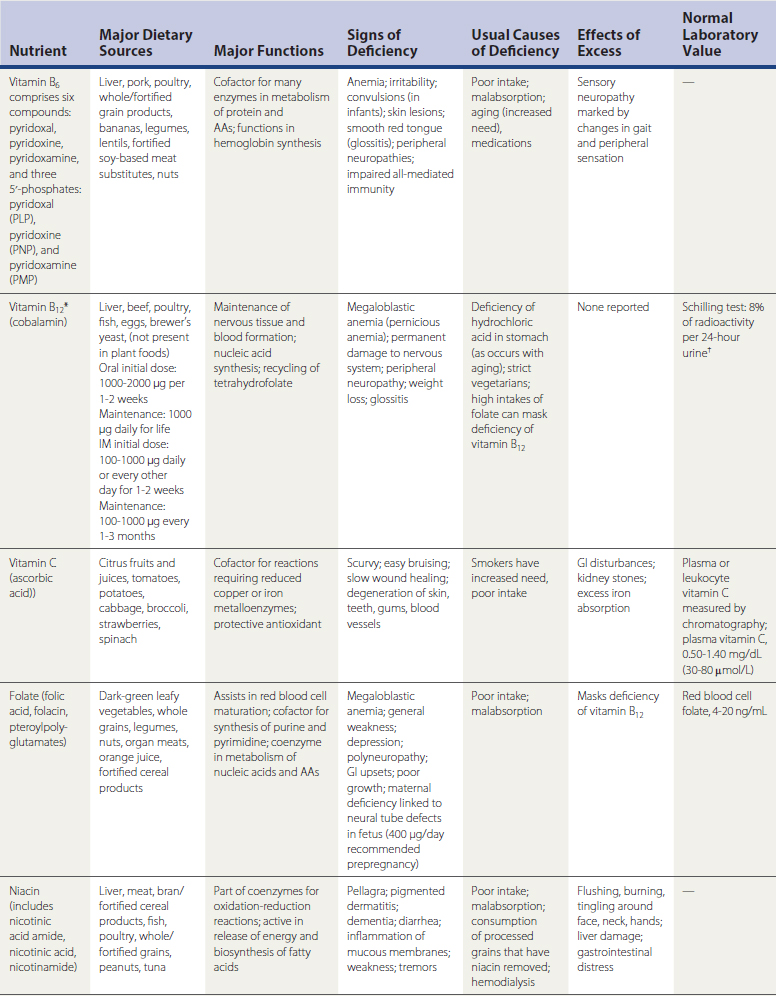

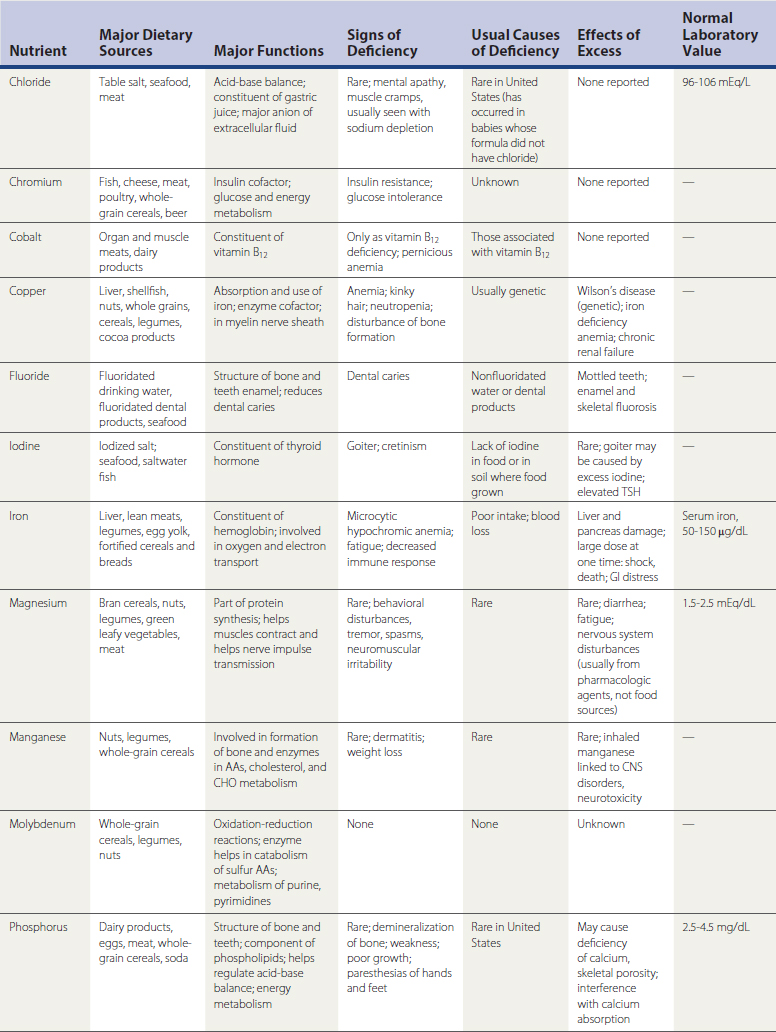

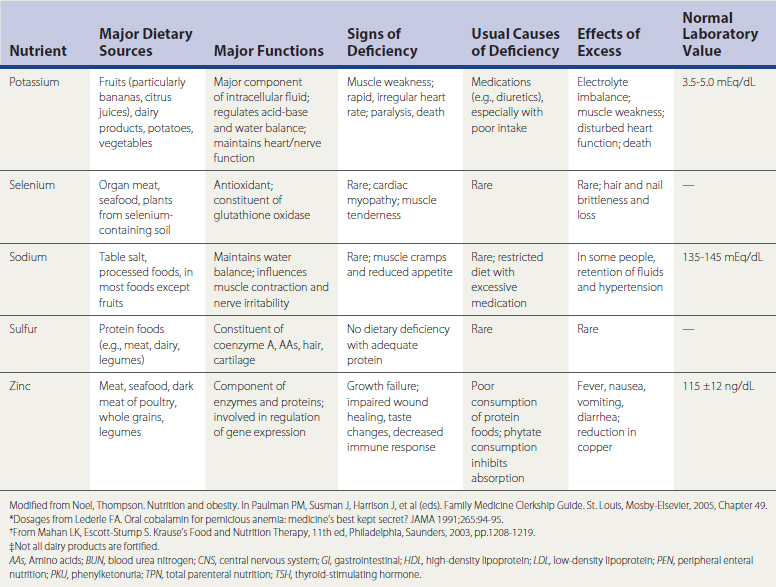

History

Patients with chronic illness deserve a more thorough history assessment, as do patients with symptoms or signs potentially related to poor nutrition (Table 37-1). Physicians should review gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and elicit information about supplemental vitamins or other nutritional products, alcohol and illicit drugs, appetite suppressants or stimulants, glucocorticoids, and laxatives. In at-risk patients or those with clinical evidence of poor nutrition, clinicians should consider the presence of conditions that may increase nutritional requirements. Physicians should also investigate the patient’s ability to obtain, ingest, digest, metabolize, and absorb nutrients; consider whether a treatment or medication will require modification of the diet; and use information obtained in the history to plan for that change.

Conditions that May Increase Nutritional Requirements

Any condition that increases the metabolic rate of the patient is likely to increase nutritional requirements (Box 37-1).

Ability to Ingest Nutrients

Various conditions may contribute to a patient’s inability or lack of desire to eat (see Box 37-1).

Digestion

A number of processes can affect the normal digestive process. Any factor that interferes with the secretion of acid or enzymes into the stomach or small intestine may impair digestion. For example, patients with partial gastrectomy or even vagotomy for peptic ulcer disease may have maldigestion and nutritional deficiencies. Similarly, patients with chronic pancreatitis may lack certain digestive enzymes and thus cannot absorb all nutrients.

Absorption

Patients may demonstrate poor absorption of nutrients for a variety of reasons, including loss of absorptive surface area in the intestinal tract from surgery, Crohn’s disease, infectious processes, or other inflammatory conditions, such as celiac disease (National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse [NDDIC], 2005) (Table 37-2). Incomplete digestion and processing of fats, carbohydrates, proteins, and vitamins can also lead to decreased absorption of those nutrients. Table 37-3 lists various nutrients and their sites of metabolism and absorption.

Table 37-2 Celiac Disease: Grains with and without Gluten

| Grains or Flours Allowed | Grains or Flours with Gluten: Not Allowed | |

|---|---|---|

Table 37-3 Nutrients and Sites of Metabolism/Absorption

| Nutrient | Site of Absorption |

|---|---|

| Macronutrients | |

| Amino acids | Throughout small intestine (more rapid proximally) |

| Sugars | Throughout small intestine |

| Fats | |

| Fatty acids | Throughout small intestine (mostly proximal) |

| Bile acids | Ileum |

| Short-chain fatty acids | Colon |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium | Duodenum, jejunum |

| Iron | Duodenum |

| Magnesium | Small intestine |

| Vitamins | |

| Folic acid | Proximal small intestine |

| Vitamin B12 | Ileum |

| Fat-soluble (A, D, E, K) | Small intestine |

Metabolism and Excretion

Many chronic diseases result in poor metabolism of foods, which leads to poor availability of calories and other nutrients. Additionally, any condition that results in excessive losses of nutrients through the intestinal tract or kidneys may also result in malnutrition. Certain foods, such as nonabsorbable fat substitutes, cause excessive loss of fat-soluble vitamins, with steatorrhea caused by the fat not being absorbed (Table 37-4).

Table 37-4 Conditions Affecting Metabolism and Excretion

| Type of Impairment | Possible Contributing Condition |

|---|---|

| Impaired dietary intake | |

| Maldigestion | |

| Malabsorption | |

| Impaired metabolism | |

| Increased excretion of nutrients | |

| Increased requirements |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Modified from Newton JM, Halsted CH. Clinical and functional assessment of adults. In Shils ME, Olson JA, Shike M, Ross AC (eds). Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 9th ed. Lippincott–Williams & Wilkins, 1999, Chapter 55.

Dietary History

It is important to obtain information about the patient’s usual and recent diet as part of the history. The dietary history refers to a patient’s usual pattern of food intake and any factors that may influence food choices and availability. Screening questions include number of daily meals and examples of food consumed. A more thorough evaluation delves into cultural or religious food practices, personal preferences, and use of the food pyramid as a tool to help patients identify food groups from which they may be consuming too few or too many servings.

Physical Examination

A systematic physical examination is important in evaluating nutritional status. General inspection may immediately reveal obvious overweight or underweight. Anthropometry, or physical measurements of an individual that are compared with reference standards, plays a role as well. These parameters include height, weight, skin fold thickness, head circumference (especially in infants and children), and waist and hip circumferences. These measurements are most helpful when taken at several intervals over time.

Height and Weight

Both height and weight are needed to calculate the body mass index (BMI), which is highly correlated with independent measures of body fat in adults (Balcombe et al., 2001; Keys et al., 1972). The formula for calculating BMI is weight (kg)/[height (m)]2. Table 37-5 lists parameters for overweight, obesity, and underweight according to the BMI (see Web Resources for BMI calculator).

Table 37-5 Weight Categories according to Body Mass Index (BMI)

| Category | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 |

| Normal | 18.5-24.9 |

| Overweight | 25-29.9 |

| Obese | ≥30 |

From National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults, BMI calculator. http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/bmicalc.htm.

General Physical Examination

Certain findings on physical examination may alert the physician to the potential for malnutrition. These include temporal wasting, decreased muscle mass in general, proximal muscle weakness, and certain skin changes, such as scaling, poor wound healing, and bruising. Tissues in the body that undergo rapid cell turnover, such as mucous membranes, skin, and hair, may be the first to show signs of nutritional insufficiency (see Table 37-1).

Laboratory Evaluation

Assessment of Protein Status

One traditional method of determining nutritional status is to measure the nitrogen balance, calculated by comparing protein gain with protein loss. In healthy adults the nitrogen balance is zero; that is, the amount of nitrogen consumed should equal the amount of nitrogen excreted. Calculation of the nitrogen balance gives an indication of short-term changes in protein status. Approximately 16% of protein mass in the body is made up of nitrogen. In calculating nitrogen balance, the clinician can determine protein intake in the diet and then measure nitrogen output in urine and feces. The nitrogen balance is negative when protein-calorie intake is insufficient; it is positive in growing children and pregnant women. The following formula is used for calculating nitrogen balance:

Nutrition in the Life Cycle

Pregnancy and Lactation

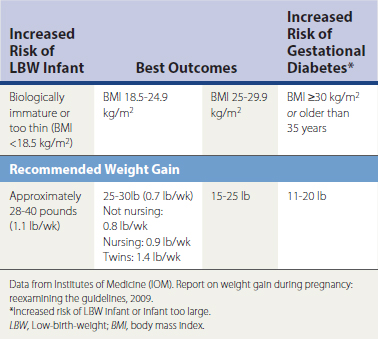

Pregnancy has long been recognized as a time of increased nutritional needs. Recommendations vary but one constant remains: with adequate caloric intake comes a greater likelihood of ingesting adequate nutrients. Weight checks are a standard part of all prenatal visits. In recent years, concern has focused on the woman’s health status after the pregnancy. As Table 37-6 demonstrates, in older pregnant women or biologically immature women (those who become pregnant within 5 years of starting to menstruate), the caloric intake and weight gain are specific to the particular health needs of the woman during as well as after the pregnancy. The usual weight retained with each pregnancy by women in the United States is 10 pounds (McGanity et al., 1999). This retained weight may have a significant influence on future chronic disease development for women.

Many of the nutritional issues in lactation are influenced by the nutritional status of the pregnant woman. The nutritional stores of the newly delivered woman are an important source of supplies for her and the infant. Certain nutrients are stable regardless of the maternal diet (Table 37-7). Studies of lactation have found that after about 6 months of breastfeeding, maternal weight decreases by about 10 pounds without any changes in the composition or production of breast milk (Barbosa et al., 1997). This may be important when considering that the average weight retained with each pregnancy is about 10 pounds.

Table 37-7 Intake of Nutrients in Maternal Diet and Effect on Amount of Breast Milk

| Intake Causes No Increase in Amount of Breast Milk | Intake Causes Some Increase | Intake Causes Significant Increase |

|---|---|---|

∗ Although supplementation is needed because of increased needs of infant (IOM. Nutrition during Lactation, 1991.)

Infancy and Childhood

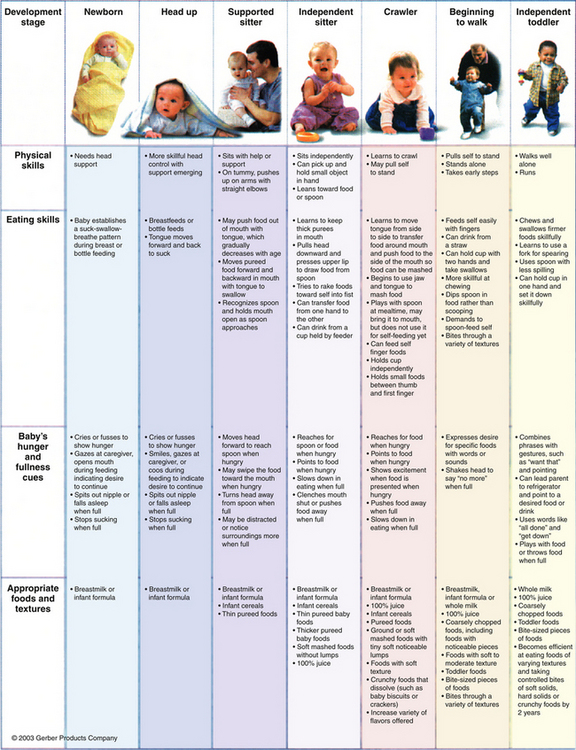

An excellent summary of the nutrients and development needs for food in this age group has been recently published (Fig. 37-1). This figure provides guidance about major nutrient needs and how the infant and child can meet these needs. These evidence-based guidelines were developed by a panel of pediatricians, nutritionists, and the U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA) after comprehensive review of the literature.

Adolescence

Adolescents gain independence by taking a greater role in food choices and amounts eaten. It is frustrating for parents who worked to establish standards to see the young person seek independence, even with foods consumed. This is a stage in life that demands high caloric intake, because growth needs are second only to those in infancy—more kilocalories per kilogram are needed than in any other life stage. This high caloric consumption is favorable to nutritional status because with high calories comes the increased likelihood of taking in more nutrients. Parents must remain hopeful that good health habits will guide the teenager. There may be concern over peer pressure leading to “strange” or different food habits, such as disordered eating, sports nutrition, and vegetarian diets, which many teens attempt. Such exploration is often a natural part of expressing independence. These food patterns can be healthy, such as improving food habits with vegetarianism or sports nutrition. The family physician needs to determine when the teen’s exploration could become harmful. Nutrition assessment is appropriate in this life stage in regard to determining whether a nutritional problem is present.