10 NURSING PRACTICE THROUGH THE CYCLE OF TRAUMA

Because of the uniqueness and complexity of patients with multiple injuries, trauma nursing has evolved as a highly specialized field that has spawned a specialty professional organization, the Society of Trauma Nurses, a journal, and certifications.1 One of the most challenging aspects of caring for trauma patients is the development of a plan of care that addresses the patient’s needs in a logical, organized fashion to ensure continuity and coordination of all care disciplines. Formulation of such a plan requires incorporation of the five components of the nursing process: assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation. In addition, nursing management is inextricably intertwined with and reflective of the plans of other trauma team members as the overall plan of care is developed and implemented throughout the cycle of trauma care.

TRAUMA NURSING PRACTICE

PROFILE OF THE TRAUMA PATIENT

• Traumatic injuries occur suddenly. Unlike a patient who is hospitalized for elective surgery, the trauma patient and family have no warning. The injury is an unexpected, severe interruption of normal life. There is no time to plan or prepare; one must simply cope with the injury once it occurs.

• Drug and alcohol abuse commonly plays a causative role in injury. The multiply injured patient whose history includes substance abuse is typically more difficult to initially assess and later to manage effectively. Often family members’ feelings of guilt because of their inability to convince the patient to seek help for a drug or alcohol problem may affect the ability to cope effectively with the family member’s injury.

• Because of the severity and complexity of injury, many trauma patients require long-term rehabilitative care. Systemic sequelae and physical handicaps also may result. Learning to adequately cope, adapt, and adjust, both physically and psychologically, can be a lengthy process.

• Psychological sequelae are common in multiply injured patients. Many experience posttraumatic stress syndrome and grieving after the injury. Depending on the individual’s existing support systems and coping mechanisms, adaptation to severe injuries may be difficult.

• Trauma continues to be primarily a disease of the young. Their inexperience with life crises, developmental stage, and level of maturity creates special needs that must be considered when planning effective interventions. In 1996, the average age of the multiply injured patient was reported to be between 15 and 34 years.2 More recently, the 2005 National Trauma Data Bank Report database shows that 21% of trauma patients are in the 14- to 24-year range, and 30% are in the 25- to 44-year range.3

• The average age of trauma patients and the number of elderly trauma patients is increasing and will continue to do so with the “graying of America.” In 1995 unintentional injury was the third leading cause of death in patients ages 45 to 65 and the seventh leading cause of death in patients age 65 and older.4 In 2004, more than 500,000 patients older than age 65 were hospitalized for nonfatal traumatic injuries, and more than 50% of these were transportation related.5 This population has unique needs that necessitate alterations in the typical approaches to resuscitation, critical care, and rehabilitative practices.

• Many critically injured patients who do not survive are potential subjects of a medical examiner’s investigation when their injuries are a result of violence or unintentional injury. Therefore legal implications must be considered as the plan of care and all documentation may be subjected to scrutiny by staff, hospital administrators, criminal investigators, attorneys, and patients’ families.

• Serious injuries are often subtle. Many injuries are obvious, and they often mask others that may be even more life threatening. Nursing assessment is of greater significance when the occurrence of subtle injuries is considered because the diagnosis may be delayed.

• The multiply injured patient has tremendous potential for developing complications during hospitalization. The nurse is largely responsible for the prevention, early detection, and for minimizing the consequences of such complications.

• Initial injuries or their required treatments create additional problems that greatly influence care planning for multiply injured patients. Many are immobilized because of orthopedic or neurologic injury. Communication is often difficult if an endotracheal tube or a tracheostomy tube is necessary for ventilatory support. The risk of developing infection is high due to the nature of traumatic injuries; multiple invasive procedures; lines, tubes, and drains; and exposure to the numerous trauma team members who provide care for them.

• Because multiple injuries affect several body systems, implementation of standard and accepted methods of treatment for each injury may be difficult or contraindicated. For example, severe brain injury may prohibit or limit routine repositioning and chest physiotherapy treatments required by a patient with thoracic injuries or respiratory failure. Alternative methods of treatment that do not compromise the patient’s existing injuries must be explored.

• The treatment of critically injured patients often imposes serious economic burdens on their families. The cost of critical care and rehabilitative care can be staggering.

Implementation of a philosophy of care that focuses on a well-communicated and organized approach to the delivery of trauma care and health care provider expertise is essential. The Committee on Trauma (COT) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) suggests the following for that approach6:

1. Rapid identification of the injury followed by easy access to the emergency medical system (EMS)

2. A central emergency dispatching system such as 911

3. Appropriately trained and appropriate level of EMS provider available to respond to the scene, that is, basic versus advanced life support

4. Prehospital triage protocols that authorize the EMS providers to make triage decisions before the patient is taken to a hospital

5. A communication system that allows direct conversation between the prehospital providers, trauma center personnel, and the physicians who provide medical direction

6. A designated trauma center with immediate availability of specialized surgeons, anesthesia providers, nurses, and emergency resuscitative equipment and radiologic capabilities

7. A trauma system that coordinates care among all levels of trauma centers and an interfacility transfer process that allows for prompt transfer of the patient to a higher level of care

8. Access to rehabilitative services in both the acute and long-term phases of recovery

CRUCIAL CONSIDERATIONS THROUGHOUT THE CYCLE OF TRAUMA

PATIENT ADVOCACY

Family Centered Care

Beginning on the first day of a patient’s admission, the bedside nurse and, if appropriate, the advanced practice nurse must assess the family members for their knowledge of the patient’s injuries and their ability to interpret and accept what has been communicated to them. Coping mechanisms and support systems that they use to deal with crisis should also be identified and documented. Research suggests that families of patients with gunshot wounds may feel more stress and have fewer coping strategies than families of patients in motor vehicle crashes; thus, interventions need to be customized to meet the needs of the specific family.7 All family information, assessment data, and the planned interventions and strategies to assist them are documented for all caregivers to refer to in the patient record. This fosters a consistent approach to the care of family members.

The initial approach with the family often sets the tone for the entire hospital stay of the patient. Joy8 suggests the following guidelines for communicating with the family in crisis:

1. Recognize that the traumatic event affects everyone associated with the injured person, including the family, neighbors, friends, coworkers, and community associates.

2. Acknowledge that family members in crisis may each express their reactions in unique ways. These include crying, fighting among themselves, being disruptive, showing anger or guilt, or being silent.

3. Overcome language barriers by obtaining appropriate interpreters to allow the family to be fully informed and fully heard.

4. Avoid using medical jargon when speaking to family members unless they are health care providers who have a full understanding of the terminology. Technical words provide little information to the family and serve more to confuse and frighten them.

5. Acknowledge the family’s concerns related to the financial impact and potential legal ramifications related to the traumatic event. Offer them the appropriate resources to answer their questions.

6. Be an attentive listener. Attempt to secure a quiet place to talk with the family so that other things happening in the clinical setting do not distract from the discussion.

Recent research supports the presence of family members at the bedside with appropriate preparation and support during invasive procedures or resuscitation.9 Family presence during these times can be beneficial to both the patient and the family in coping with the psychologic effects of critical illness and injury. Early assessment and appropriate nursing interventions such as providing information, active listening, facilitating flexibility in visiting, and family caregiver conferences are key to effective family-centered care and management of families of trauma victims.10

Visiting Considerations

Family visits are a vital part of the overall plan of care and can influence patient outcome. Visiting by family members and others should be encouraged during all phases of the cycle of trauma care. Patient and family needs are important considerations in the nurse’s individualization of visiting practices. Flexible visiting policies that include the family, friends, children, and even pets have been implemented successfully in a number of institutions.10–13 Visits provide the nurse with an opportunity to assess the family’s understanding and perception of their loved one’s injuries and to provide information. Families who are restricted from visiting a critically ill member often suffer fear, anxiety, hopelessness, and helplessness. These may be displayed as hostility and anger toward the staff in an attempt to appear in control of the situation.

The Dying Patient

Occasionally, conflicting opinions among the medical staff, nurse, and family regarding the continuation of aggressive treatment arise. In these situations the nurse must assume the role of coordinator and patient advocate. The nurse’s roles include: working with all team members; involving appropriate resources such as the chaplain or ethics committee to assist in decision making and emotional support of the family and the health care team; participating in development of a final plan of care that is implemented consistently; and documenting the decisions in the patient’s medical record.14,15

COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE

Collaborative practice can significantly affect morbidity and mortality of the critically ill.16 Critical care units with the most effective, high-quality care have highly coordinated systems for patient management. Excluding other variables, investigators have concluded that the process of care is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality. Inherent in the process is the positive interaction and collaboration of physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals in achieving optimal results and the adherence to established protocols and procedures to guide their care.17 Hope for the survival of the multiple trauma patient rests with the collaborative efforts of the paramedics, trauma nurses, physicians, technicians, and therapists who constitute the trauma team and who work together to resuscitate, stabilize, diagnose, and treat the severely injured patient.

Quality care of trauma patients implies minimal errors and complications and maximal efficiency and continuity. Quality care can only be provided by a team that accurately and consistently communicates, beginning with the field providers and subsequently with the nurses and physicians who follow the patient from admission throughout the resuscitative and operative phases. Strategies that can improve collaboration and communication between health care providers as well as improved patient outcomes include use of formal, written guidelines and protocols, multidisciplinary rounds, and the addition of nurse practitioners to the health care team.18 The incorporation of nurse practitioners into the trauma care team has significantly increased over the past decade and the role has become an essential one in many trauma centers.19 In 2005 the Society of Trauma Nurses released a position paper on the role of the nurse practitioner in trauma.20

STRATEGIES TO PLAN AND PROVIDE QUALITY CARE AND PATIENT SAFETY

Highly specialized trauma care requires numerous strategies for the planning and provision of care. Policies and protocols specifically addressing the care of trauma patients should be developed and based on current, evidence-based literature. It is imperative that the established protocols, policies, standards, and procedures be reviewed on a consistent basis and updated to reflect and incorporate new modes of therapy, technology, and recent research findings. As well, policies, procedures, protocols, and guidelines need to be consistent with the standards and guidelines set forth by organizations such as the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma (ACSCOT), the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the Society of Trauma Nurses, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Care Delivery Models

A system of nursing care delivery capable of providing highly specialized care and ensuring continuity of care through the cycle of trauma is paramount. Primary nursing, and the more recently espoused relationship-based care model21 are examples of care delivery systems that facilitate the coordination of specialized care across the continuum of trauma care. The nurse is central to the goal-directed coordination of the many care providers who are involved in the management of a trauma patient’s care. Other systems of care delivery may be equally effective, as long as they ensure nursing accountability for patient and family-centered care, interdisciplinary goal-directed care, and for communication and coordination within the trauma team.

The Plan of Care

The written plan of care is a vital component of the trauma patient’s care. The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) requires a documented plan of care that addresses physiologic, psychologic, and environmental factors.22 The care plan for the trauma patient satisfies this regulatory requirement and serves as the link between injury and readaptation—the basis from which all care is delivered. This plan should be developed by, familiar to, and used by all members of the trauma team. It must be succinct and reflect changes in care as they become necessary. The plan also should be evaluated and revised at regular intervals, dictated by patient acuity and specific goals or outcomes. Ideally a consistent “relief nurse” should assume this responsibility in the absence of the primary or coordinating nurse.

Clinical Pathways, Protocols and Guidelines

In the past two decades, clinical pathways, protocols, and practice guidelines have been developed to save time, to ensure consistent, evidence-based quality care for trauma patients, and to allow measurement of quality outcomes. Standardization of practice is increasingly advocated by thought leaders in the area of trauma care.23,24

Consistent incorporation of evidence-based protocols for high-volume diagnoses and care processes into daily management of patients has been shown to reduce complications and mortality.25 In addition to utilization of multidisciplinary protocols, critical care units and hospitals with lower than predicted critical care unit and hospital mortality use daily interdisciplinary rounds to enhance communication, monitor adherence to guidelines and protocols, regularly report outcome data, and incorporate findings into clinical performance improvement initiatives.

Computerization of the medical record facilitates utilization of standardized clinical decision support and management plans, affords individual patient customization, and allows monitoring of patient outcomes related to compliance with protocols and guidelines.

Evidence-Based Practices

Patient care that is driven by research-based protocols and guidelines enhances patient outcomes, allows measurement of outcomes by reducing practitioner preferences, and increases the cost-effectiveness of care and resource use. For example, protocols for suctioning, tracheostomy care, tracheostomy changes, head of bed elevation, and oral care should be integrated into the pulmonary care regimen for all patients.26 Prone positioning, institution of kinetic therapy, and early mobilization are other examples of evidence-based interventions that can reduce the risk of nosocomial pneumonia and improve oxygenation and ventilation.27,28

The use of specialty beds and mattress overlays has become common practice in the care of the multiply injured patient. When prescribed appropriately, they can enhance the patient’s recovery process. The placement of a patient on one of these beds should be a collaborative nursing and medical decision based on specific criteria. Identification of risk factors for development of respiratory failure or nosocomial pneumonia29 and guidelines for placing patients on these beds prevent unnecessary or inappropriate use and expenditures. For instance, kinetic therapy beds have proven to be efficacious in reducing the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia and other immobility-related complications when instituted within 72 hours of admission and rotated for 15 hours per day.27 Prone positioning and beds to facilitate prone positioning can improve both oxygenation and ventilation in critically ill trauma patients with acute respiratory failure.28 The use of air-fluidized or low-air-loss beds reduces the risk of pressure sore development and enhances healing of large wounds. These are appropriate for patients who are at high risk for skin breakdown as determined by a risk assessment such as the Braden scale.30

The belief that rehabilitation begins on admission has long been accepted, but it is particularly relevant when planning care for the trauma patient. At the time the patient enters the critical care phase, rehabilitation needs are addressed according to protocol to minimize the impact of immobility on all systems and lessen the possibility of delayed recovery. Attempts to reduce musculoskeletal alterations begin in the critical care phase. Early splinting of extremities when appropriate, active and passive range of motion exercises, and frequent repositioning aid in prevention of serious contractures and other musculoskeletal problems arising from immobilization. Literature also supports the application of pneumatic leg compression devices early after hospital admission to deter the development of deep vein thrombosis related to injury and immobility.31

In the past decade, the use of evidence-based initiatives has included protocols called “bundles.” These have been embraced and championed by interdisciplinary organizations, such as the Institute for Health Care Improvement and professional health care organizations such as the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Trauma Nurses, and Emergency Nurses Association. For example the 100,000 Lives Campaign32 includes a “ventilator bundle” to prevent ventilator-acquired pneumonia and guidelines for rapid response teams, preventing adverse drug events, preventing surgical site infections, and preventing central line infections. Similarly, a “sepsis bundle” (from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign33) is an evidence-based approach to early detection and aggressive management of infection and sepsis.

Nurses managing patients throughout the phases of trauma are responsible for continually and critically analyzing their practice to ensure that the most recent and best evidence is incorporated into care of the trauma patient, and that practices are not based on outdated information and traditions.34,35

IMPACT OF PHARMACEUTICAL AND TECHNOLOGIC ADVANCES

Nursing care during the resuscitation, critical care, and acute care phases has become increasingly specialized and complex. Pharmacologic and technologic advances continue to improve the care of critically ill trauma patients. As new drugs and devices become available and are incorporated into patient care, nurses are challenged to maintain a high level of expertise and keep abreast of the indications for use, desired physiologic effects, side effects or complications, and other related implications. For example, administration of new therapeutic agents, such as drotrecogin alfa36 and recombinant factor VIIa,37,38 are increasingly common in the trauma population and have significant nursing implications associated with their administration. The clinical pharmacist, as a trauma team member, is an invaluable resource to the nurses and physicians, not only as new pharmacologic agents are introduced but also in the routine management of the patient receiving multiple medications.

The use of sophisticated technology in trauma care requires a high level of expertise and competence. Nurses and other staff members must be properly educated and credentialed before assuming the responsibilities of caring for patients supported by sophisticated life-support devices. Extracorporeal lung assistance and continuous renal replacement therapy are examples of therapies in which the nurse must monitor the device’s function and the patient’s response and manipulate multiple variables (e.g., gas flow rates, blood flow rates, and fluid and electrolyte replacement) accordingly. In addition, advances in ventilatory support technologies for traumatically injured patients, such as airway pressure release ventilation, that are directed toward preventing acute lung injury or aiding the management of acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS)26,39 demand increasing collaborative, interdisciplinary education programs as well as collaborative care.

A system of equipment evaluation and control is important. For example, it is advantageous to have all units use the same monitoring system or emergency equipment so that the entire staff can become familiar with and secure in its use. Evaluation, acquisition, and integration of new technology are important aspects of trauma/critical care nursing. Participation in the technology assessment and value analysis process, developing specific criteria for use and establishing outcome measures, and planning the integration and education processes are important aspects of the nurse’s role.40

When using highly technical equipment, computer systems, and other devices, the trauma nurse should know that an important role is humane caring. Naisbitt’s theory41 of “high tech, high touch” is relevant to the trauma patient’s care and should be incorporated in the plan of care. This formula describes the way we have responded to technology. Whenever new technology is introduced into society, there must be a counterbalancing human response—that is, high touch—or the technology is rejected. High technology is inherent and ever-expanding in the trauma/critical care field.

Naisbitt acknowledges that there is no way to keep humans from devising new tools, but we must take care not to use these tools as the sole solution. Particularly in this age of increased technology use, health care providers have a personal responsibility to provide humane care, recognizing the need for human touch.41 As the need for more high-touch care increases, ensuring consistent patient care is essential to providing holistic care and optimizing patient outcomes. In addition, consideration of the care environment is important to minimize the untoward effects of high-tech resuscitation and critical care areas. Strategies to promote physical and psychologic healing for the patient and family include reducing extraneous noises, using dim and indirect lighting, using soft colors, hanging pictures and photographs, and playing music of the patient’s choice.42

PHASE I: FIELD STABILIZATION AND RESUSCITATION

The ultimate goal in the prehospital phase is to stabilize and transport the multiply injured patient to the appropriate level trauma center via the safest and most rapid transport mode.43 Accomplishing this requires collaboration that begins at the scene where the patient is injured. An effective EMS system provides a means for specially trained paramedics to communicate with trauma physicians at the receiving hospital and a centralized communications center to assist in planning the appropriate mode of transport for that patient. Conditions at the scene also may require calls for additional personnel to help with extrication or additional law enforcement officers to assist with crowd control or to direct traffic to prevent further injuries. In addition to the indispensable role of the paramedic, the role of the nurse and physician in the field can be of great value, as the concept of “go teams” (physicians and nurses who go from the hospital to the scene) has illustrated. In addition, flight nurses (and physicians in some programs) who staff hospital-based helicopter programs are in widespread use across the country. The three priorities for the prehospital providers at arrival on the scene are (1) scene assessment, (2) evaluation of individual patients, and (3) recognition of possible multiple patient involvement and mass casualty incidents.43

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS

The Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS), Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS), and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) guidelines for initial assessment provide a standardized approach to care in the prehospital setting.43–45 In the field or at the scene of any injury, the priorities and primary survey are based on ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure).

Establishing an airway at the scene can be difficult. The injured individual may be trapped inside a vehicle with a steering wheel crushed against the chest or may have been ejected from the vehicle, resulting in serious head and facial injuries with severe bleeding causing airway obstruction. EMS personnel suspect the trauma patient of having a cervical spine injury until proved otherwise, and an airway should be established with this possibility in mind.

Immediately following attention to the ABCs, neurologic status and disability should be assessed. The baseline neurologic status (level of consciousness and pupillary size and reaction) of the trauma patient is so critical that it must be included as part of the primary assessment.43 Exposing the patient by removal of clothing is important to identifying all injuries. However, only the amount of clothing necessary is removed to protect the patient from the environment, particularly in colder climates. Once the primary survey has been completed, a secondary survey is performed to establish the presence of further injuries.

DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN

Documentation from the field is crucial to the plan of care. EMS records should include information on patient status, vital signs, mechanism of injury, therapy received, and present medical history (if relevant). Any relevant social history (e.g., involvement of other family members) is also documented. Injury data include time of injury, geographic location, and any other pertinent data. These prehospital written records become part of the patient’s permanent medical record and are kept because the data from them are essential in completing data requirements for trauma registries and databases. In addition, most trauma center verification or designation standards also require that the prehospital sheets be present in the medical record. Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), together with several agencies throughout the country, developed a standard prehospital dataset and a dataset dictionary, available online with data entry systems.46

EVALUATION

After the patient has reached the trauma facility, it is important that the trauma team reviews the prehospital care. Any identified concerns from the prehospital phase of care (e.g., esophageal intubation, inappropriate triage or treatment decisions) should be communicated back to the prehospital jurisdictional leadership or appropriate persons. This is essential for improving quality in the trauma system as a whole. EMS representatives are key stakeholders in trauma center System Performanace Improvement Committees.

In summary, an effective plan of care for the injured victim begins at the scene of the injury. In the 1970s, Dr. R. Adams Cowley, father of the “golden hour” concept, found that multiple trauma patients who received definitive care within 60 minutes of their injuries had the best chance for recovery.47 Rapid assessment, treatment, and transport, and clear communication during this phase will impact all subsequent stages of the patient’s care.

PHASE II: IN-HOSPITAL RESUSCITATION AND OPERATIVE PHASE

PREPARATION AND INITIAL CONTACT

The resuscitation nurse plays a vital role prior to the patient’s arrival. Requisite equipment for treating all injury priorities is established by ASCOT in the ATLS manual.44 This equipment should be readily accessible and located in the area where the trauma patient arrives. In some institutions proximity of the resuscitation area to the operating room (OR) may be such that the trauma resuscitation area must be able to support major surgical procedures in emergency situations. The design of some small resuscitation areas and emergency departments makes this a challenge, but every second lost as a result of disorganization decreases the patient’s chance of survival. Receiving prior notice of a patient’s arrival allows preparation of routine equipment and supplies and acquisition of any unusual equipment required for specific injuries. Preassembled sterile instrument trays should be readily available to save valuable time.

Members of the trauma team are notified prior to patient arrival and must be present when the patient is admitted. In major trauma centers this team usually consists of an attending (trauma surgeon or emergency medicine physician), a trauma fellow, one or two emergency medicine or surgery residents, one or two nurses, a respiratory therapist, anesthesia personnel, and a patient care technician. Response times and presence of these individuals is dictated and monitored by the trauma center verification or designation process. Preparation also includes donning of appropriate protective attire (goggles/face shield, mask, gloves, and water-impervious cover gown) before the patient’s arrival.48 These CDC guidelines and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requirements are considered to be the minimal personal protection by ASCOT for all health care providers who may be in contact with the patient’s body substances.44 Each member of the team is assigned a specific role during the resuscitation, which is determined before the patient arrives.

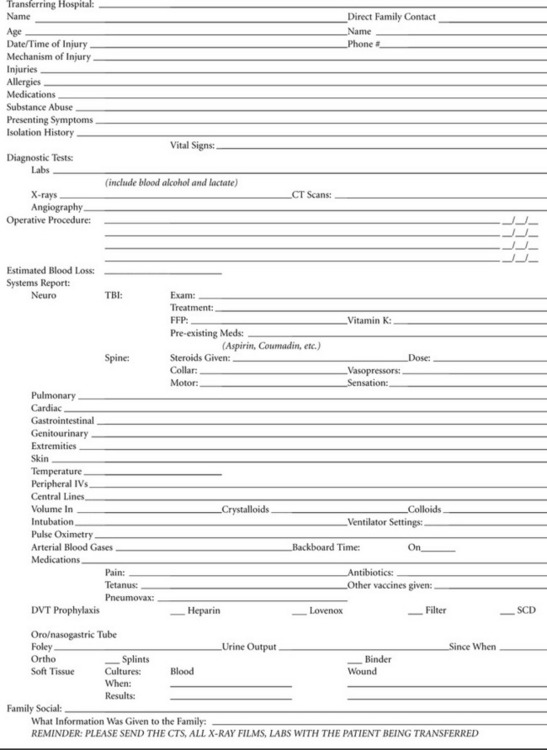

Some patients may be initially treated and stabilized in a hospital that does not provide a full complement of trauma services. These patients are subsequently transferred to a higher level trauma center. Before transfer, these patients may require aggressive management to achieve hemodynamic stability and adequate tissue oxygenation while preventing further deterioration. Of great importance is the documentation and communication of events prior to transfer. When the referring facility communicates with the receiving hospital, the report should include the data shown in Table 10-1.

TABLE 10-1 Example of Report Form Used to Provide Patient Information to Receiving Hospital from Transferring Facility

|

TBI, traumatic brain injury; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; SCD, sequential compression device.

Courtesy of RA Cowley Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree