Nonosseous Injuries

Keith D. Cook

Nonosseous or soft tissue injuries can be a perplexing entity for both the physician and patient. Whereas one can assess healing of a fracture or osseous injury through radiographic studies, and progression of the patient toward full-weight-bearing and normal shoe gear can occur, the healing of soft tissue injuries is often based on the subjective report of the patient. The slow healing of a patient with a nonosseous injury can be quite frustrating to the treating physician, who must decide if the patient’s symptoms are real or if the patient is a malingerer. This can be particularly difficult with the workman’s compensation patient.

Nonosseous injuries can range from a simple contusion to a more complex compartment syndrome, with devastating consequences if improperly treated. Nonosseous injuries can be classified as acute or chronic. This chapter focuses on the acute soft tissue injuries; however, many types of acute soft tissue injuries including tendon ruptures and ligament injuries are covered elsewhere in this textbook.

Although most commonly encountered in the emergency room or trauma center, the foot and ankle surgeon should be prepared to treat these injuries in the office or clinic setting. After the patient is stabilized, a thorough history and physical examination including all pertinent ancillary studies should be obtained. This chapter discusses some of the more common nonosseous injuries encountered by the podiatric clinician and the author’s treatment recommendations for each.

CONTUSIONS AND HEMATOMAS

Contusions are soft tissue injuries caused by blunt trauma in the absence of a break in the skin or fracture (1). Ecchymosis and edema are generally present, and pain can be elicited on direct palpation of the contused area. Treatment consists of rest, ice, compression with an elastic tape or wrap, and elevation (the RICE principle). Weight-bearing is progressed as tolerated; however, initially, the limb may be too painful to ambulate on and crutches may be necessary for non-weight-bearing.

Careful attention should be given to the patient who develops a hematoma as a result of blunt trauma. Resolution of the hematoma usually occurs; however, if the pain does not subside, the hematoma may need to be evacuated. If possible, needle aspiration is performed with an 18-gauge needle; however, in some circumstances, a formal incision and drainage is required in the operating room.

TECHNIQUE

The author prefers to evacuate the hematoma, by making an incision directly over the hematoma formation and bluntly dissecting down to the level of the fluid collection. The wound is pulse lavaged with 3 to 6 L of normal saline; antibiotics are not required in the lavage. In the presence of an expanding hematoma, the wound should be thoroughly inspected for any actively bleeding blood vessels. Actively bleeding blood vessels are ligated or repaired as needed. The wound is then packed open with iodoform packing material. The first dressing change is performed 36 to 48 hours postoperative.

PEARLS

When evacuating a hematoma, the tourniquet although applied to the patient’s limb should not be inflated, unless there is uncontrolled life-threatening bleeding. This allows for better visualization of any ruptured blood vessels.

The author places skin sutures across the incision at the time of the original incision and drainage. The sutures are not tied and the long ends of the sutures are held down with the use of Steri-Strips. The sutures can then be tied at bedside and the wound closed 4 to 7 days postoperative without necessitating a return trip to the operating room.

COMPLICATIONS

With any type of blunt or high-energy trauma, the clinician must have a high index of suspicion for a compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome is discussed later in this chapter. However, if a compartment syndrome or expanding hematoma is not recognized and treated emergently, soft tissue necrosis may occur.

BLISTERS

Blisters or bulla are the separation of the skin dermal and epidermal layers with the accumulation of clear, sterile fluid between the layers. Blister formation is the result of friction, usually caused by improperly fitting shoes when they occur on the feet (1).

Lancing of the bulla with drainage of the fluid is a common treatment for blisters. The bulla should be lanced at its most dependent location to allow for drainage of the fluid and to prevent fluid reaccumulation and recurrence of the blister. Friction blisters should not be deroofed because the overlying epidermis serves as a natural biologic dressing.

TECHNIQUE

A no. 11 surgical scalpel is utilized to lance the surface of the blister. The author prefers to pie crust the lesion or lance the blister in multiple locations. This technique helps in preventing fluid reaccumulation. The overlying epidermal skin should have the appearance of a split-thickness skin graft upon completion of the pie crusting technique.

A nonadherent compressive dressing is then applied to the wound. The dressing can be changed daily until the affected area of skin has completely healed. The patient is also educated about wearing properly fitting shoes and appropriate socks for the activities in which they participate. Removing the etiology of the blister formation is essential for preventing recurrence of the lesion.

PEARLS

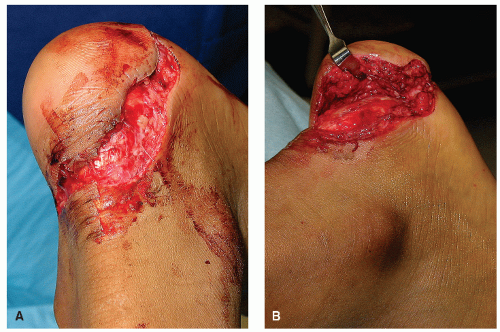

This technique for pie crusting friction blisters can also be utilized when treating serous fracture blisters. However, hemorrhagic fracture blisters require deroofing and treatment of the underlying wound as an ulceration (Fig. 90.1). The author treats these wounds with silver sulfadiazine cream, a nonadherent compressive dressing, and appropriate splinting as dictated by the fracture (Fig. 90.2).

Any surgical intervention should be delayed until the patient’s soft tissue envelope is adequate for incision healing.

LACERATIONS

Lacerations are unplanned wounds through the skin epidermis and dermis (2). A thorough history and physical examination needs to be performed, and the patient’s tetanus status should be ascertained. Appropriate tetanus prophylaxis needs to be given to the patient. The mechanism of injury and duration of time from the injury also need to be determined. The mechanism of injury will help the treating physician in determining what types of contaminants are present in the wound as well as the extent of soft tissue damage. Lacerations that have been left untreated for greater than 8 hours are generally not closed initially and may need to heal secondarily.

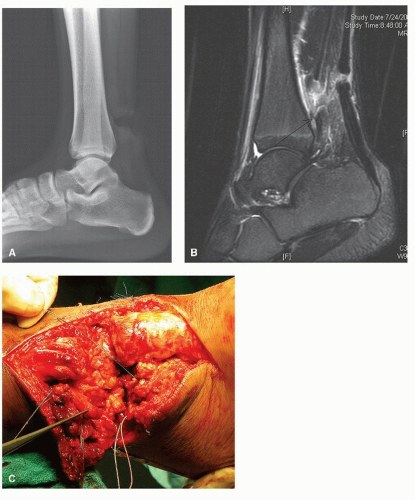

Lacerations may be simple straight wounds with well-approximated edges that tend to suture close easily or they may be more complex with jagged edges and have a soft tissue crush component involved. These more complex lacerations may need to be treated in the operating room with excision of the jagged edges and utilization of plastic surgery techniques for proper closure (Fig. 90.3).

All lacerations should be inspected for deeper tissue damage and involvement of underlying structures. Any laceration involving damage to tendons, nerves, joint capsules, or vascular structures should be thoroughly explored in the operating room setting. Consultation with a vascular surgeon or neurosurgeon may be necessary when vascular structures or nerves have been transected (Fig. 90.4).

TECHNIQUE

Simple or minimally jagged lacerations may be closed in the emergency room or office setting. First, the laceration needs to be anesthetized with a local anesthetic, administered via a field block or by infiltrating the area around the laceration. Care should be taken not to inject the anesthetic directly into the wound edges as this may create unwanted tension across the laceration. Next, the wound is irrigated to remove debris and hematoma, and to aid in reducing bacterial contamination. The wound is inspected for damage to deeper structures at this time.

Prior to suturing, the area is prepped with either chlorhexadine gluconate or a povidone-iodine solution. If a povidone-iodine solution is used as either an irrigant or for prepping the skin, the clinician must be aware of the cytotoxic effects of the povidone-iodine and the risk of impaired wound healing (3,4 and 5). Any small jagged edges should be excised at this time providing for linear wound closure.

When the clinician is confident all debris has been removed from the wound and the wound is clean, then it may be sutured. Closure of foot and ankle lacerations usually can be achieved with either a 3-0 or 4-0 nylon suture material in a simple interrupted fashion. Care must be taken to realign all relaxed skin tension lines when possible, placing minimal tension across the wound. Deep absorbable sutures also in a simple interrupted fashion may be required for deeper lacerations. A bacitracin adaptic compressive dressing is applied. Non-weight-bearing status should be instituted for all lacerations on the plantar aspect of the foot. Increased tension across the repaired laceration may result in suture failure and wound dehiscence.

The sutures are generally removed in 10 to 14 days for dorsal or lower leg lacerations and 21 days for plantar foot lacerations.

However, well-coapted wound edges should be noted before removing any sutures.

However, well-coapted wound edges should be noted before removing any sutures.

PEARLS

The author irrigates lacerations with a 1-L bottle of normal saline. An 18-gauge needle is utilized to create two or three holes in the cap of the bottle. Compression of the bottle then creates an adequate lavage system for irrigating lacerations or wounds of the foot and ankle.

The use of simple interrupted sutures allows for removal of individual sutures should a hematoma or infection develop. In general, antibiotics are not required for clean lacerations; however, antibiotics should be considered in wounds that are heavily contaminated or that occur in patients who are immunocompromised. The most common organism found following a pedal traumatic event is Staphylococcus aureus (6). An oral antibiotic with good gram-positive coverage, such as a first-generation cephalosporin, is used in these scenarios.

FROSTBITE

When treating any patient who presents with a lower extremity frostbite injury, the presence of systemic hypothermia must always be considered. Hypothermia exists when the core body temperature is less than 95°F (35°C) and signs of shivering, slow mentation, muscle rigidity, hypotension, and depressed respiration are present (7,8). It is paramount that the systemic hypothermia be treated before or simultaneously with the extremity frostbite.

Frostbite occurs when the patient’s extremity has been exposed to cold conditions, generally following a period of wetness. The frostbite patient usually does not present during a snowstorm but presents to the emergency room a few days later when the temperature is still below freezing and their feet had already become wet. Predisposing factors of frostbite include advanced age, alcoholism, psychiatric disorders, poor nutrition, drug use, previous cold injury, homelessness, any disease restricting blood flow to the extremity, tight fitting shoes or clothing, and skin exposure. Frostbite occurs through a process of extracellular and intracellular crystal formation followed by vasoconstriction, resulting in inadequate tissue perfusion (9,10).

Two classifications are currently employed when describing frostbite injuries. The first describes the injury from first degree through fourth degree, with the tissue penetration becoming deeper and the prognosis for salvage worsening as the degree increases. Whereas first-degree frostbite presents with hyperemia and edema, fourth-degree frostbite injuries involve necrosis, loss of tissue, and bone destruction (9,11). The second classification system is more simplistic and only has two categories, superficial frostbite and deep tissue frostbite. Superficial frostbite involves the epidermis and dermis without deeper extension. The tissues are resilient and the prognosis for salvage is better. Deep frostbite involves the epidermis and dermis with extension to deeper tissues including tendons and bone. The tissues are less resilient and the foot or affected area is stiff. The prognosis for salvage is poor (1,12). For our purposes, the following treatment techniques will be for the latter classification system.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree