CHAPTER 67 Nonimplantation Salvage of Severe Elbow Dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

Today, several salvage options exist for severe elbow dysfunction following trauma or failed prior intervention. If the joint is stiff and destroyed, interposition arthroplasty is recommended (see Chapter 69). If strength is required in a young person, especially if the joint is infected, fusion may be considered (see Chapter 70). If the injury is to the brachial plexus, strategies for management are discussed in Chapter 71. In this chapter, we review resection arthroplasty and allograft reconstruction for massive bone loss.

RESECTION ARTHROPLASTY

TECHNIQUE

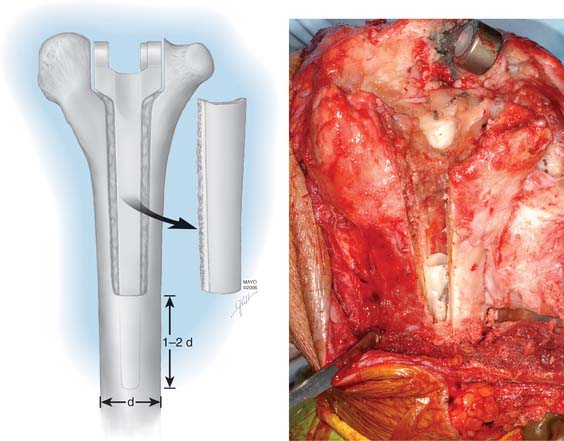

To remove a well-fixed implant, a trapezoid-shaped cortical window is removed from the posterior aspect of the distal humerus (Fig. 67-1). Care is taken to preserve the epicondyles (Fig. 67-2). The olecranon is positioned between the two columns. We use a No. 3 PDS suture to help stabilize this relationship.

AFTERCARE

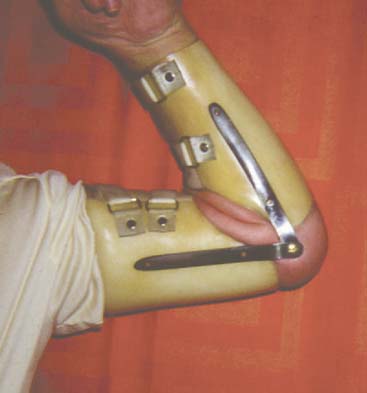

A cast is applied for 6 weeks. Protected motion is begun using a Mayo Elbow Brace (Donjoy International, Vista, CA) and continued for an additional 6 to 8 weeks (Fig. 67-3).

RESULTS

We have just completed an assessment of 59 resected elbows after failed total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) for sepsis at a mean time of 12 years after surgery. Although the study is still under way, preliminary analysis demonstrates a clear distinction between those with “contained” articulation (Fig. 67-4) having medial and lateral condyles doing markedly better than those with more extensive resection preventing any opportunity for a fulcrum effect (Fig. 67-5). Custom orthotic braces are occasionally prescribed, but infrequently worn on a regular basis (Fig. 67-6).

FIGURE 67-4 Two years after resection arthroplasty, notice the maintenance of the medial and lateral columns.

SEGMENTAL BONE LOSS

The unstable or “flail” elbow with segmental bone loss, that is, complete loss of articulation and ligament attachments, is difficult to manage. Treatment with a primary replacement is discussed in Chapters 59 and 66. This problem can be a sequel of trauma, infection, failed elbow arthroplasty, or tumor resection. Bone may be lost at the original injury following a severe open fracture, or it may be removed subsequent to infection, particularly if the fragment is avascular. In treating recalcitrant union of supracondylar fractures, surgeons have in the past (and disastrously) succumbed to the temptation to remove the condylar fragment of the humerus and treat the problem by inserting an endoprosthesis.

If the problem is limited to just the articular region of the humerus, a hemireplacement may be effective (Fig. 67-7). If, however, all stability and distal contour of the humerus is lost, today, a linked replacement is performed for such patients (see Chapter 59).

On the other hand, in the situation of a flail elbow, particularly in a young patient, arthrodesis may be considered (see Chapter 70). However, failure of fusion, even under optimal conditions, has been high in some series2,14,16 and successful arthrodesis is unlikely in patients with large bone stock deficiencies. Reconstruction procedures, such as those involving reattachment of muscles more proximally on the humerus or interposing a tongue of triceps muscle into the gap, are unlikely to be successful. Muscle transfer procedures can improve flexion in cases of flail elbow associated with paralysis, but in these cases, the problem is of a different nature. A successful outcome will occur only if a stable fulcrum is provided and muscles are restored to their normal functioning length.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree