CHAPTER 27 Nerve Problems About the Shoulder

Patients with shoulder pain or injuries not infrequently have concomitant neurologic conditions, and orthopaedic surgeons caring for such patients must be aware of them. In addition, the practice of reconstructive shoulder surgery carries an inherent risk of iatrogenic injury to neighboring neurologic structures. Knowledge of the common nerve lesions about the shoulder allows surgeons to recognize these entities when they see them, and familiarity with the relevant neural anatomy will help them avoid potential neural injuries when they operate. Surgeons must have a systematic approach to evaluating and treating these challenging patients with nerve-related disorders about the shoulder region.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Examining shoulder abduction is an important part of the examination both to record muscle strength and to visualize shoulder kinesis through the arc of motion. Two important points are relevant here. First, some patients can abduct the shoulder through a full arc of motion by using either just the supraspinatus or the deltoid in the face of complete paralysis of one or the other. Ensuring muscle contraction is a critical element in this part of the examination. Second, visualizing and palpating the scapula are a necessary part of the examination, especially when one is faced with dysfunction. For example, patients with winged scapulae from either serratus anterior or trapezius weakness might have difficulty abducting the arm fully without the scapula stabilized and might compensate with trick motions. Physicians should recognize the clinical appearances and know the techniques to examine winging of the scapula, particularly with respect to distinguishing serratus anterior, trapezius, or rhomboid muscle dysfunction. In addition, a useful test for serratus anterior function, in which the inferior pole of the scapula is stabilized and the patient pushes the arm forward, can be applied even in a patient with a complete brachial plexus lesion; patients unable to push their arms forward could not otherwise perform the more standard push-off test with the arms extended against the wall.

MUSCULOCUTANEOUS NERVE INJURY

Etiology

Musculocutaneous nerve injury is most commonly associated with severe brachial plexus trauma. Although the nerve can be injured in glenohumeral dislocation, it is unusual to diagnose such injury as an isolated neuropathy.1 If it is seen as an isolated nerve injury, it is most often associated with a form of penetrating trauma, open surgical reconstruction, or a direct blow to the chest (near the coracoid). Occasionally, musculocutaneous neuropathy can occur after strenuous physical activity such as rowing.2

The musculocutaneous nerve travels obliquely below the coracoid process and enters the coracobrachialis. The anatomy of this juncture has been investigated in several studies. Small branches of the nerve can be found inserting into the coracobrachialis as close as 17 mm below the coracoid.3 The main trunk of the musculocutaneous nerve enters the coracobrachialis approximately 5 cm from the coracoid and exits at 7 cm.3,4 The nerve then enters the biceps, typically more than 10 cm from the coracoid.4 The nerve is at risk during anterior shoulder procedures that result in significant retraction medially or during medial surgical dissection. The Bristow procedure has been thought to be associated with injury to the nerve,5 but such injury is probably related less to transfer and more to manipulation of the nerve.6

The nerve can also be damaged during arthroscopic surgery, although such injury is quite rare. Anterior portals straying medial to the coracoid put the musculocutaneous nerve and other branches of the brachial plexus at potential risk for injury. Low anterior portals such as the 5-o’clock portal can bring instruments to within 10 mm of the nerve.7 A patient with a musculocutaneous nerve lesion typically has a mixed sensory and motor lesion. Less commonly, a pure sensory lesion of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, the distal sensory termination of the musculocutaneous nerve, can occur. Lesions of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve at the level of the elbow often have an atraumatic etiology and must be distinguished from more proximally occurring (incomplete) musculocutaneous lesions manifesting with sensory loss. These patients might have numbness or paresthesia along the lateral elbow crease that extends distally along the anterolateral aspect of the forearm. Treatment involves splinting or corticosteroid injection and, possibly, surgical exploration.8 Surgical exploration on occasion reveals a thickened aponeurosis compressing the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve as it transits between the biceps and brachioradialis muscles. Patients might respond to surgical decompression of the nerve in this area.9

Operative Treatment

If biceps and brachialis function are not seen to improve either by clinical examination or by electrophysiologic studies, surgical exploration should be undertaken, ideally before 6 months has transpired from the injury. Surgical treatment options vary for persistent musculocutaneous neuropathy. If at surgical exploration the nerve appears intact but compressed by scar and demonstrates electrical conduction across the lesion, neurolysis may be indicated. If a neuroma in continuity (that does not conduct a nerve action potential [NAP])10 or a rupture or transection of the nerve is discovered, additional treatment options should be considered.

In patients who have an isolated musculocutaneous nerve injury, a standard approach is to perform interpositional nerve grafting across the lesion. However, nerve transfers could also be used to shorten the distance (and time) for reinnervation or to bypass a scarred or avascular segment. A new nerve transfer is the Oberlin transfer, a technique in which one or two fascicles of the ulnar nerve are transferred directly to the motor branch to the biceps.11,12 The distance to achieve reinnervation is extremely short because the site of repair is in the proximal part of the arm (several centimeters from the biceps end-organ) rather than a more lengthy repair from the neck or shoulder region. This technique can be used in patients with upper plexus lesions. Grade 3 or 4 Medical Research Council (MRC) function was achieved in more than 90% of patients treated with this technique in two large series (each with more than 30 patients).12,13 Reinnervation in the biceps was noted approximately 3 months after the procedure. Importantly, no patient suffered loss of distal ulnar nerve function or sensation. Recent modifications of this procedure have been reported with double reinnervation of elbow flexion: An ulnar nerve fascicle may be transferred to the biceps motor branch, and a median nerve fascicle may be transferred to the brachialis branch.14,15

If patients are seen longer than 1 year after musculocutaneous nerve injury, nerve repair or reconstruction is significantly less likely to be effective.16–22 Still, in select cases, nerve transfer techniques can be considered.

AXILLARY NERVE

Anatomy

It is easy to locate at surgery during an anterior exposure by sweeping an index finger inferiorly over the anterior subscapularis and gently hooking the axillary nerve while simultaneously palpating the nerve on the underside of the deltoid with the other index finger.23 As it exits the space, the nerve continues to the posterior aspect of the humeral neck and divides into anterior and posterior branches. The position of the anterior branch is commonly reported as lying 4 to 7 cm inferior to the anterolateral corner of the acromion.24 The posterior branch innervates both the teres minor and the posterior portion of the deltoid. The branch to the teres minor usually arises within or just distal to the quadrilateral space and enters the posteroinferior aspect of the teres minor muscle.

The internal topography of the axillary nerve has been studied by Aszmann and Dellon.25 As the nerve leaves the posterior cord, it is monofascicular, but as it enters the quadrilateral space, it has three distinct groups of fascicles: motor groups to the deltoid and teres minor and the sensory group of the superior lateral cutaneous nerve. The deltoid motor fascicles are found in a superolateral position; those of the teres minor and superior lateral cutaneous nerve are located inferomedially.

Etiology and Clinical Manifestation

Most axillary nerve injuries occur as part of a combined brachial plexus injury; isolated axillary nerve injury occurs in only 0.3% to 6% of brachial plexus injuries.26 Injury to the axillary nerve most often follows closed trauma involving traction on the shoulder. Axillary nerve paralysis is the most common neurologic complication of shoulder dislocations. Some patients with a proximal humeral fracture or shoulder dislocation have a subclinical axillary nerve lesion that is evident by EMG/NCS but that is not apparent clinically because of the associated discomfort.27–31 The vast majority of these patients recover from the nerve injury as they rehabilitate from the dislocation or fracture. Blunt trauma to the anterolateral aspect of the shoulder has also been noted to cause axillary nerve injury as it travels on the deep surface of the deltoid muscle.32

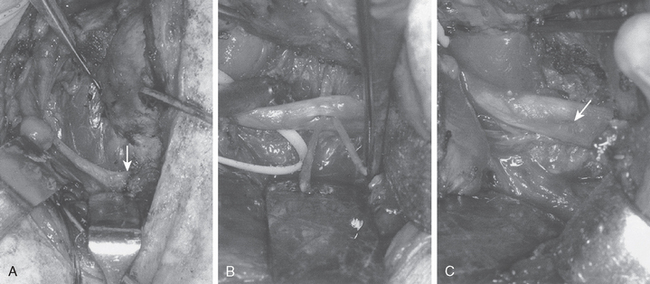

Open reconstructive surgery (Fig. 27-1) or newer arthroscopic techniques can put the axillary nerve at risk. For example, capsular shrinkage procedures can create a local increase in temperature in the inferior capsule that can lead to nerve injury.33,34 The nerve has been reported to be injured in 1% to 2% of thermal capsular shrinkage procedures, but fortunately, the vast majority of these injuries seem to be only temporary.35 The axillary nerve is also at risk during capsular resection for adhesive capsulitis.36 Because the nerve is in close proximity to the anteroinferior capsule, great care should be taken when resecting in this area. A safer method of inferior capsular resection in this area is to visualize the axillary nerve with the arthroscope during the procedure.

Nonoperative Treatment

Young patients may be able to compensate for complete deltoid paralysis and can often perform activities of daily living with only partial disability. The shoulder can easily maintain a full range of motion with an intact rotator cuff. However, most patients have early fatigue in the involved side if asked to perform repetitive activities. Although deltoid atrophy is quite evident in a fit person, in a less-fit patient, the examiner occasionally finds it difficult to detect deltoid atrophy. Injury to the superior lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm can lead to sensory loss over the lateral aspect of the shoulder. It is possible for patients with a complete deltoid motor deficit to have only mild loss of sensation over the lateral part of the shoulder. The diagnosis of axillary neuropathy should not be determined by the presence or absence of lateral shoulder sensation. It is unclear whether the sensory branch is spared from injury or whether the sensory zone is supplied by overlapping innervation from other cutaneous branches.

The quadrilateral space syndrome has been described as another potential cause of posterior shoulder pain, and it presumably results from compression of the axillary nerve within the quadrilateral space. This syndrome is a controversial clinical entity; it might simply be a manifestation of Parsonage–Turner syndrome (brachial neuritis). Tenderness may be noted posteriorly along the shoulder joint; otherwise, the clinical examination is often normal. Deltoid atrophy or lateral sensory changes are uncommon, and EMG examination is usually normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might demonstrate signal change indicating denervation in the deltoid and teres minor muscles.37 Observation is the usual treatment for quadrilateral space syndrome, and the vast majority of patients improve with time.38 Surgical exploration of the quadrilateral space and release of scar or fibrous bands to achieve decompression of the axillary nerve are rarely needed.39

The results of nonoperative treatment of a blunt traumatic lesion have generally been good. Leffert stated that axillary nerve injury after fracture or dislocation is more common than usually appreciated, yet the majority of patients progress to full recovery.40 In a study of 73 patients with proximal humeral fracture or dislocation, 33% were noted on EMG to have an axillary nerve injury, with 9 complete and 15 partial lesions.41 All patients recovered with no objective loss of function, including those with complete nerve lesions. In a series of 108 elderly patients with anterior shoulder dislocation, 9.3% were found to have an axillary nerve injury, but all patients went on to full recovery by 12 months.27 Nonetheless, some patients do not make the expected recovery. In these patients, surgical exploration with neurolysis or possibly nerve grafting can be undertaken if no clinical or EMG recovery is evident by 3 to 4 months.42–45 If the patient has a history of a sharp penetrating wound or if a surgical injury has occurred, surgical exploration should be performed at an earlier date.

Operative Treatment

The proximal monofascicular structure of the axillary nerve with primarily motor fibers and its relatively short length from the posterior cord to the deltoid motor end plate are characteristics that lend themselves to surgical intervention. Alnot and Valenti reported on 37 axillary nerve surgeries, including 33 cases of sural nerve grafting, 3 neurolysis procedures, and 1 direct repair.42 In 23 of the 25 isolated axillary nerve lesions, M4 or M5 strength was achieved. The fact that 33 of the 37 patients required sural nerve grafting illustrates the difficulty in adequately mobilizing the nerve for direct repair. The small number of patients undergoing neurolysis (3 of 37) is an indication that mild nerve compression by scar or fibrous bands is not common. Repair of the nerve with a short interposed cabled sural nerve graft has been the most common method and has demonstrated the most consistent results.43,46–50

Other techniques for repair of the axillary nerve include nerve transfer. Direct neurotization with a donor nerve such as the medial pectoral, thoracodorsal, or radial has yielded satisfactory results in cases in which direct repair or short cable grafting of the axillary nerve itself is not possible or not preferable.51–53 Nerve transfers using the spinal accessory nerve or upper intercostal nerves have been described but require an interpositional sural nerve graft53,54 and have demonstrated less-optimal results.53,55 A recent nerve transfer using a triceps branch to the anterior division of the axillary nerve has been described in cases of upper trunk brachial plexopathy,56 and because of promising results it is now being used by some surgeons instead of nerve-grafting techniques in cases of isolated axillary paralysis.

Alternatively, the pectoralis major can be transposed laterally on the clavicle and acromion. Mobilization of the pectoralis major is limited somewhat by the relatively tight anatomic dimensions of the pectoral nerves. If the deltoid is completely paralyzed, the trapezius can be mobilized off the clavicle and spine of the acromion, and the lateral acromion with attached trapezius can be inserted into the proximal end of the humerus. This procedure can restore some shoulder abduction to a patient who has none; however, it does create a change in the normal slope of the shoulder and therefore has a less than desirable cosmetic result. More-advanced techniques such as free muscle transfer have been attempted, but the results have been less than uniform.

SPINAL ACCESSORY NERVE

Etiology

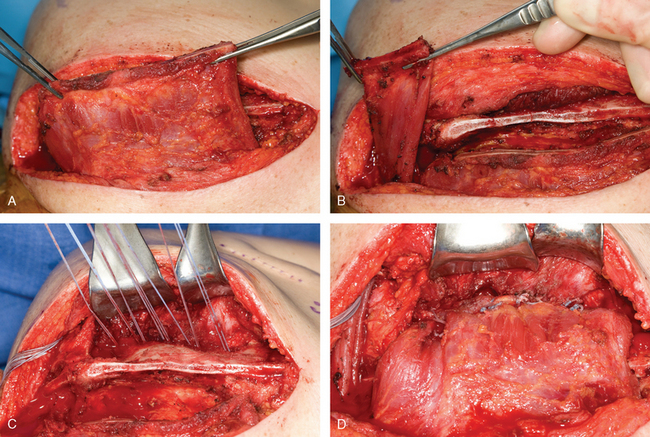

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve can occur after penetrating trauma to the shoulder. Blunt trauma can also cause loss of trapezius function. Most commonly, surgical dissection in the posterior triangle of the neck, such as for lymph node biopsy, can expose the nerve to possible damage (Figs. 27-2 and 27-3).57–61

Anatomy

The spinal accessory nerve passes through the upper portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which it innervates, and then crosses the posterior cervical triangle. The posterior cervical triangle is bordered anteriorly by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, posteriorly by the trapezius, and inferiorly by the clavicle. The nerve lies on the floor of the posterior triangle with only the overlying fascia as protection against injury.62 It abuts the posterior cervical lymph nodes. The nerve enters the anterior surface of the trapezius and travels inferiorly, parallel to the medial border of the scapula.63 The trapezius has a broad origin from the ligamentum nuchae to the 12th thoracic vertebra and inserts over the lateral part of the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula. The upper trapezius is the prime elevator of the scapula and acts to upwardly rotate the lateral aspect of the bone.

Diagnosis

If the spinal accessory nerve is injured, the diagnosis is often missed, and appropriate treatment may be delayed.57 Patients usually have vague shoulder pain as their primary complaint. Loss of motion may be a secondary concern. Unless trapezius function is specifically tested, the diagnosis might not be recognized. Because of the common occurrence of anterior shoulder pain in these patients, with occasionally only slight visible wasting of the trapezius muscle, the pain may be assumed to represent postoperative pain or be misinterpreted as resulting from another condition associated with shoulder pain, such as rotator cuff pathology. The trapezius receives some innervation from the upper cervical nerve roots, so complete atrophy of the muscle might not occur.

Some of the pain that patients experience might come from strain of the other parascapular muscles as they attempt to compensate for the lack of trapezius function. Additionally, because the scapula cannot properly rotate the acromion away from the humerus as the arm is elevated, impingement of the rotator cuff can cause secondary rotator cuff tendinopathy. If attention is directed only at the rotator cuff, the underlying nerve pathology will be missed. In addition, the spinal accessory nerve, though mainly a motor nerve, still has sensory fibers. Injury to the nerve can also produce neuropathic pain. Finally, one should also examine for possible concomitant injury to other neighboring nerves such as the cervical plexus or great auricular nerve.

Operative Treatment

Whenever possible, surgical exploration of the nerve should be performed by 6 months. Although surgical reconstruction of the nerve may be considered up to a year after injury, better results occur with treatment as soon after injury as possible.57,58,60 We favor early exploration of these nerve injuries when they occur immediately after surgery, especially when the nerve was not identified and protected as part of the operation.

Surgical options include neurolysis, direct repair, or nerve grafting, depending on intraoperative observations and electrophysiologic testing. During surgical reconstruction, it is important to consider the acromion–mastoid distance in the anesthetized patient. If direct repair of the nerve is performed with the head tilted toward the operated shoulder, when the patient is awakened after surgery and transported to the recovery room, significant traction can occur and disrupt the repair. If the nerve ends are found to have retracted at surgery, it is best to use an intervening graft such as a sural nerve or the great auricular nerve to put less tension on the repair (Fig. 27-4).

Nerve Transfer

Nerve transfer using a pectoral branch can be performed in cases of proximal injury to the accessory nerve, inability to identify proximal stump, or late referral.64 If more than 12 to 18 months have passed since injury to the spinal accessory nerve, nonoperative treatment may be considered if the patient has compensated reasonably well. The degree of disability varies from patient to patient, even despite aggressive physical therapy. Some have only a persistent ache in the shoulder, whereas others feel and act completely disabled with respect to the upper extremity. Braces have been advocated as adjunctive treatment, but they are bulky and not used consistently by patients.65 A patient symptomatic enough to attempt to use a brace is potentially a candidate for surgical reconstruction.

Muscle Transfer

Modern surgical procedures currently involve dynamic muscle transfer techniques. Earlier historical procedures, however, initially involved mostly static repairs. Henry and others advocated static stabilization of the medial aspect of the scapula to the vertebral spine with strips of fascia lata.66–68 Dewar and Harris described lateral transfer of the levator scapulae to the lateral part of the scapula combined with a static fascial sling from the vertebral spine to the medial part of the scapula.69 Static repairs with fascia, tendon, or artificial materials, however, tend to stretch out or rupture over time.70

Dynamic transfer of the levator scapulae along with the rhomboid major and rhomboid minor was described in Germany by Eden and Lange.71–73 Bigliani reported good results with this technique.61,74,75

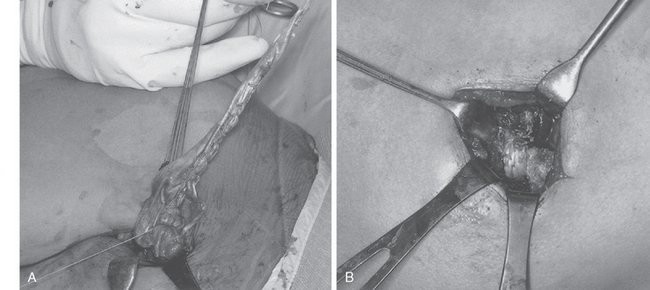

The infraspinatus is partially elevated off of the scapula in a medial-to-lateral direction. The rhomboids are then placed as far lateral as possible–at least 4 cm–on the posterior aspect of the scapula and secured in place via suture and drill holes through the scapula. Alternatively, the rhomboid minor can be transferred cephalad to the spine of the scapula into the supraspinatus fossa. The infraspinatus is then sutured back in position over the transferred rhomboids.

This technique has shown good results, probably because it involves dynamic transfer of muscle rather than a static transfer, which might stretch or possibly wear out over time.73 If an Eden–Lange procedure or a static transfer fails and a salvage situation exists, scapulothoracic fusion becomes a potential option. Scapulothoracic fusion should be reserved primarily for patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy and global loss of shoulder muscle function. Different techniques have been used to perform scapulothoracic fusion, but most involve passing wires through the scapula and around several ribs with a broad iliac crest bone graft or metallic plate for support. The complication rate can be high, with the potential for pneumothorax or hardware failure.

LONG THORACIC NERVE

Etiology

The nerve is rarely injured as a result of penetrating trauma, but injury can occur from thoracic outlet surgery in the region of the first rib, breast surgery, or lateral chest wall procedures such as axillary node dissection.76,77 Spontaneous cases of entrapment at the scalenus medius have been described.78 Probably, the most common cause of serratus anterior dysfunction is Parsonage–Turner syndrome. In fact, this condition is most likely the underlying cause of dysfunction attributed to overexertion, including athletic activities.

Clinical Manifestation

Isolated injury to the long thoracic nerve is usually manifested as winging of the scapula. Velpeau first described injury to the long thoracic nerve causing paralysis of the serratus anterior in 1837.79 However, winging of the scapula has multiple causes, with multidirectional instability probably being the most common cause of mild winging. Spinal accessory nerve injury can also cause winging, but this injury tends to be milder and results in more of a rotational deformity of the scapula. Additionally, some patients have volitional control over the scapula and can demonstrate significant winging at will.

Nonoperative Treatment

In our opinion, in idiopathic or nonpenetrating trauma cases, observation is the standard therapy. No specific physical therapy protocol has been found to be especially helpful other than continued use of the shoulder as tolerated. Braces have been advocated to help hold the scapula against the chest wall.80 Though somewhat effective, braces are usually found to be awkward and are not well tolerated by patients. Most patients with a nontraumatic or idiopathic cause tend to recover from the paralysis and regain serratus anterior function within 6 months to 1 year.81

Operative Treatment

Potential surgical options are available for treating injury to the long thoracic nerve in the early stages. Some have favored neurolysis of the nerve with decompression at the level of the scalenus medius.78 However, because it is difficult to be certain where the lesion resides or if compression (rather than inflammation, for example) is responsible for the dysfunction, we do not recommend this approach for most patients. In cases where no spontaneous recovery has occurred, another strategy is to perform neurotization (or nerve transfer) using one or two intercostal nerves or the thoracodorsal nerve.82,83 Because it is not usually clear where the damaged section is, the nerve can be connected with the donor nerve close to the motor end plate. This technique has been helpful in a small number of reported cases.82,83 Many patients with atraumatic lesions recover spontaneously, so we do not routinely recommend surgery to the average patient before 6 or 9 months after the nerve deficit develops.

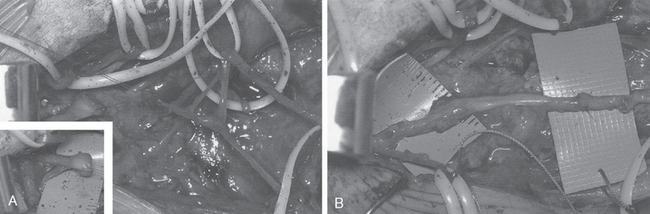

If a patient does not recover serratus anterior function and use of the shoulder is compromised, a number of reconstructive options are available (Fig. 27-5).76,84–95 Scapulothoracic fusion has been performed when the scapula is fixed to the underlying ribs. Although this technique can eliminate winging of the scapula, it will decrease shoulder girdle motion by at least 30%, with mostly forward elevation and extension affected.96 Pneumothorax is a risk with this technique, and the pseudarthrosis rate is not insignificant. For these reasons, scapulothoracic fusion should be reserved for the salvage situation or for patients with symptomatic facioscapulohumeral dystrophy.

Tendon Transfer

Tendon transfers provide dynamic control of a winging scapula and are now our preferred method in patients who have had a neurologic deficit for 1 year or more. Tubby described transfer of the pectoralis major to the serratus anterior in 1904.94 Although this transfer might offer initial relief of the winging, the paralyzed serratus anterior tends to stretch out with time, and this procedure is not recommended today. Other techniques described include transfer of the pectoralis minor, rhomboids, or levator scapulae.85,88,97

Pectoralis Major Transfer

The technique that seems to give the most consistent result is transfer of the pectoralis major to the scapula with tendon graft augmentation. Durman, Ober, and Marmor90,98,99 each described successful transfer of the pectoralis major with a fascial extension graft in a few cases. More recent studies have demonstrated the excellent ability of this tendon transfer procedure to control winging of the scapula.86,89,91,92,100,101 The pectoralis major is ideally suited as a transfer to substitute for the paralyzed serratus anterior. The direction of pull of the pectoralis major is similar to the path of the serratus anterior, and the bulk of the pectoralis major provides enough strength to resist winging of the scapula. The technique has been used with transfer of the entire pectoralis major or with only the sternal head (Fig. 27-6). Equally good results have been reported with both procedures. However, the sternal head of the pectoralis major is much more in line with the direction of pull of the serratus anterior than the clavicular head is, and it also provides for a less bulky transfer. Moreover, the sternal head is more substantial than the clavicular head and provides a stronger tendon transfer. Potential concerns of cosmesis or visible deformity of the anterior chest wall should be minimal. In most instances, regardless of whether the entire pectoralis major or the sternal head is transferred, there is little change in the normal contour of the anterior chest.

Technique

At surgery, the patient should be positioned in the lateral decubitus position for easy access to the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder. The anterior approach is usually performed while a second surgical team is simultaneously harvesting fascia lata. This approach is made somewhat easier by the lateral position. The anterior incision (4-6 cm) is made almost entirely in the axil lary crease and is extended only a centimeter superiorly. This technique results in a well-hidden, cosmetic incision. The sternal head of the pectoralis major is easily identified at the inferior margin of the muscle. The sternal head wraps posteriorly under the clavicular head and inserts more medial and superior to it. The sternal head is detached directly off the humerus, with care taken to avoid damage to the biceps tendon. The sternal head is then freed up medially onto the chest wall to allow greater excursion of the muscle. The harvested fascia lata graft should measure approximately 14 × 5 cm. The fascia lata is rolled into a spiral tube, draped around the pectoralis major tendon and muscle, and secured with multiple sutures. A heavy running locking suture is then placed through the fascia lata graft and tagged for transfer.

Postoperative Management

Postoperatively, the patient is told to use the sling full-time and to avoid any abduction of the shoulder. At 6 weeks after surgery, the sling may be discarded and the patient allowed to resume all normal daily activities with the arm. No lifting of objects heavier than a kilogram is permitted. A formal physical therapy program is not usually necessary. Patients tend to regain a normal range of motion quite readily. It is assumed that healing takes place during the initial 3- to 6-month period, and therefore return to manual labor or sporting activities is allowed after 6 months. Early failure has occasionally been reported after pectoralis major transfer, and such failure seems to be related to premature return to full function before complete healing.86,89

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree