CHAPTER 82 Neoplasms of the Elbow

INTRODUCTION

Most benign and malignant tumors of bone and soft tissue are relatively rare, and their occurrence in the region of the elbow is even more unusual. Although there are no valid statistics on soft tissue tumors, compilation of data from the files of the Mayo Clinic until December 2003 indicates that only 1% or so of bone tumors occur at the elbow (Table 82-1). Hence, no single entity is likely to be encountered very often at this site.

TABLE 82-1 Bone Tumors—Mayo Experience: Updated, 2003

| Type of Tumor | Number at Elbows | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Benign | ||

| Osteoid osteoma | 25 | 397 |

| Osteochondroma | 16 | 884 |

| Giant cell tumor | 13 | 682 |

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | 2 | 50 |

| Osteoblastoma | 1 | 108 |

| Malignant | ||

| Malignant lymphoma | 38 | 905 |

| Ewing sarcoma | 15 | 611 |

| Osteosarcoma | 16 | 1984 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 3 | 285 |

| Angiosarcoma | 1 | 109 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 6 | 1080 |

| Malignancy in giant cell tumor | 2 | 39 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 1 | 98 |

| Myeloma | 19 | 1069 |

*Does not include patients with multiple exostoses.

Unfortunately, comparable figures are not available for benign and malignant soft tissue tumors, although our impression is that the most common benign soft tissue tumor in the elbow region is the lipoma. Ganglia and myxomas are also occasionally seen in this region. Of the malignant soft tissue tumors, epithelioid sarcoma and synovial sarcoma are probably the most frequently encountered at this joint. The locally aggressive desmoid tumor may also occur at or near the elbow. Metastatic disease usually originates from the breast or kidneys.55

Tumors that occur in the region of the elbow are unique in that because there are a relatively large number of important structures in a relatively small and confined area, there is little normal tissue that can be spared; and it may be difficult or impossible to remove a tumor with a margin of normal tissue on all sides without severely compromising the function of the forearm and hand. In this respect, tumors that occur at the elbow, particularly those in the antecubital fossa, are comparable with tumors that occur in the region of the knee. However, the upper extremity is probably considered more important by most patients and their physicians; hence, amputation surgery is probably less likely to be carried out for these tumors than for those of the lower extremity. In addition, it is generally considered difficult to fit a patient with an upper limb prosthesis; and even if upper limb prosthetic devices are prescribed, patients are often reluctant to use them. In contrast, most patients readily accept the use of a lower limb prosthesis. An amputation may be required for aggressive or malignant tumors to achieve adequate surgical margins, and yet both the patient and the physician may be reluctant to accept this radical treatment. Finally, as with traumatic conditions, the tumor or its treatment often renders the elbow stiff and restricts function.27,54

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Following the clinical examination, radiographs in at least two planes should be obtained.22 Computed tomography (CT), with a comparison of the opposite elbow joint, may yield useful information, particularly in terms of planning for the surgical procedure. The authors have not found the performance of routine arteriography to be particularly helpful in this or any other site; however, if one needs to know the relationship of the tumor to the adjacent major vessels, contrast material can be used when CT is performed, thereby supplying this information more simply and safely than by performing routine arteriography.

Magnetic resonance imaging has proved to be particularly valuable in the assessment of both bone and soft tissue tumors in most areas, including the elbow. Soft tissue tumors can be defined as to the extent of disease and their relationships with major neurovascular structures. Information about the extent of medullary involvement can be ascertained for bone tumors.

STAGING

The staging system of Enneking and colleagues,24 which includes both soft tissue and bone sarcomas, is useful. This system has two main factors, the first of which is the biologic potential of the lesion. If the lesion is benign, it is labeled G0. If it is malignant, it is judged to be either a low-grade (G1) or a high-grade (G2) lesion; the high-grade lesions have a greater potential for metastatic spread. The second factor is the anatomic site of the lesion; that is, whether it is entirely within a surgical compartment (T1) or whether it extends outside the compartment (T2). With these classifications, a low-grade malignant tumor that is entirely within a single compartment is a 1A lesion; a low-grade lesion that extends into a second compartment is a 1B lesion; a high-grade malignant tumor that is confined to a single compartment is a 2A lesion; and a high-grade tumor that extends into a second compartment is a 2B lesion. Any tumor that shows evidence of metastatic spread is considered a stage 3 lesion.

The terminology suggested by Enneking23 describing surgical procedures is now generally accepted. Thus, if a lesion is entered at surgery, the procedure should be considered an intralesional resection; if a tumor is “shelled out,” the procedure should be considered a marginal resection; and if there is a margin of normal tissue on all aspects of the resected specimen, the operation should be considered a wide excision. For the procedure to be judged a radical resection, all the structures within the involved compartment must be resected. When the lesion involves bone, the entire bone must be removed if the procedure is to be considered a radical resection.

PROSTHETIC REPLACEMENT

With improved designs and techniques, we have improved our outcomes with the use of prosthetic replacement for both primary and metastatic diseases.3,54 The majority (90%) were treated for metastatic diseases. Satisfactory outcomes may be expected given that the overall prognosis of these patients is guarded, with a mean survival time of only 3 years3 (Fig. 82-1).

BONE TUMORS

BENIGN BONE TUMORS

Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma

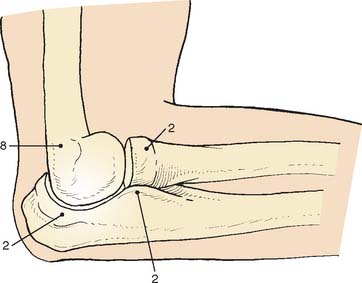

Osteoid osteoma arising in an intra-articular location is relatively uncommon; however, it may occur in the region of the elbow. It is relatively common at the elbow, but only a few reports on the presentation,36 diagnosis,33 and management41 have appeared. This small benign bone tumor occurs in patients of any age, most commonly children and young adults. As with most bone tumors, boys and men are more commonly affected than girls and women. Unremitting pain is the usual symptom for which the patient seeks medical attention; however, progressive loss of motion may also be a characteristic feature. Pain during the night is particularly prominent. Aspirin may afford very dramatic relief of pain, a fact that may even suggest the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. Occasionally, the pain may be experienced at a site remote from the lesion. Another peculiar feature of this tumor is its occasional association with atrophy of the adjacent soft tissues. In the Mayo Clinic’s experience with 14 such cases, eight have occurred in the distal humerus, four in the ulna (two coronoid, two olecranon), and two in the radial head–neck region60 (Fig. 82-2).

As noted previously, when osteoid osteoma occurs at or near the elbow joint, there is characteristically loss of some flexion or extension, but pronation and supination are preserved. In addition, there may be a synovial reaction that may further confuse the diagnosis. The most striking feature of these tumors is the prolonged average time required for making the diagnosis. In the Mayo Clinic’s experience, the delay to diagnosis averaged almost 2 years.60

The osteoid osteoma, by definition, is small, usually no more than 1.5 cm in diameter. Lesions that are clinically and histologically similar but are 2 cm or more in diameter are referred to as osteoblastomas; these lesions have clinical features somewhat different from those of osteoid osteoma,48 but loss of motion is a common feature.8,27 Osteoid osteoma is small when first encountered and remains small,30 further complicating the diagnosis.

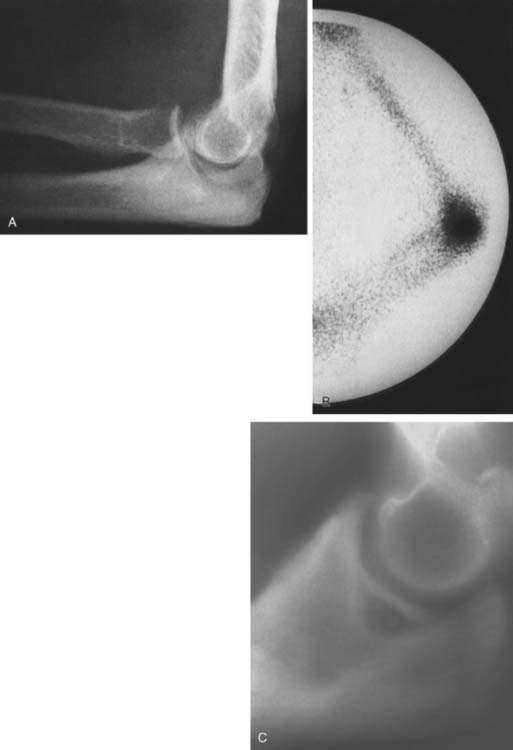

An extensive diagnostic evaluation is usually required in determining the precise location of the osteoid osteoma.12,34 When the patient complains of unremitting pain in the elbow, plain radiographs are obtained (Fig. 82-3). These may or may not reveal the presence of the tumor. The lesion typically appears as a central small nidus, which is a radiolucent area usually surrounded by an area of sclerosis. It is this sclerosis that is usually seen38; the central area of the nidus is more difficult to identify. When the lesion is located on the surface of the bone, there may be periosteal new bone formation thatfurther obscures the nidus.36 Cronemeyer and colleagues13 described an unusual radiographic feature of osteoid osteoma in the elbow joint—subperiosteal new bone formation in adjacent bones; for example, an osteoid osteoma in the distal end of the humerus that exhibits periosteal new bone formation in the proximal radius and ulna.13 These authors concluded that “awareness of this association will prevent misdiagnosis of the benign neoplasm as an inflammatory arthritis.”

Technetium-99m scintigraphy has been helpful in locating these lesions.33 If technetium-99m scintigraphy reveals no abnormality, an osteoid osteoma is unlikely; however, if the bone scan is positive, further diagnostic studies of the involved area should be undertaken (Fig. 82-4). If there is any significant synovial reaction, there may be increased uptake owing to the synovitis as well as to the lesion itself.51,52 Sometimes, multiple radiographs must be taken before the lesion can be identified. Today, CT is the diagnostic standard, however, if the tumor is so small it may be missed on this examination.55

Grossly, there is usually some sclerotic bone surrounding a central nidus. This nidus may be somewhat redder than the surrounding cortical bone and has been described as having the appearance of a small cherry. It is sometimes helpful to obtain radiographs of the excised block of tissue before the pathologist cuts into the block. Microscopic examination of the surrounding bone shows no unusual features; the nidus itself consists of a network of osteoid trabeculae (see Fig. 82-3).

Treatment.

In the past, the treatment of osteoid osteoma was surgical excision of the nidus. It is not necessary to remove all of the sclerotic bone. The main problem with this type of surgery is identification of the lesion and confirmation of its removal by the pathologist, which may be difficult. Ghelman and associates26 have described a method for localizing an osteoid osteoma intraoperatively using a scintillation probe. This technique may simplify the localization of the lesion at the time of surgery. Patients whose lesions are not completely excised will probably continue to have the same pain and will probably require a second operation.50 The authors have observed that the loss of motion so characteristic of this lesion at the elbow resolves with removal of the nidus. Hence, capsular release is not necessary as an adjunctive procedure.60

Osteochondroma

Osteochondroma is probably the most common benign bone tumor, but it is not very commonly encountered in the elbow. The incidence may be somewhat higher than that reflected in our surgical experience, however, because many osteochondromas in other locations are asymptomatic and presumably may also be in the region of the elbow. The osteochondroma is not inherently painful but causes symptoms by pressure on adjacent structures. The tumor may be found in a patient of any age, but it usually stops growing when skeletal maturity is reached. An osteochondroma may arise from the surface of any bone but most commonly does so in the metaphyseal region of long bones (Fig. 82-5). The tumor tends to project away from the joint along the direction of attached muscles. The tumor may be pedunculated on a stalk or may be sessile and have a broad base (Fig. 82-6). The tumor is covered by a cartilage cap, which, if it becomes markedly thickened, suggests the possibility of sarcomatous transformation. If it is more than 1 cm thick, the risk of secondary chondrosarcoma is relatively high. In children, the cartilage cap is normally thicker than in adults. Probably fewer than 1% of osteochondromas ever become malignant.29

FIGURE 82-5 Osteochondroma in a 23-year-old woman. Radial shaft with cortical and medullary bone extending into tumor.

FIGURE 82-6 Osteochondroma of the distal humerus in a 41-year-old man. Note the soft tissue reaction.

Osteochondromas in the region of the elbow may cause mechanical difficulties; specifically, interference with the motion of the elbow joint. In addition, the cartilage cap may impinge on important neurovascular structures. If there are symptoms or mechanical or cosmetic difficulties, complete excision of the osteochondroma, together with the overlying cartilage cap, is performed. Excision commonly involves the use of an osteotome to shave the lesion level with the underlying cortical bone. Such simple excision generally results in cure, although local recurrence may occasionally be noted, indicating that part of the cartilaginous cap was left behind. If the cap is thicker than 1 cm in an adult, the lesion must be carefully studied histologically to exclude the possibility of a sarcoma.

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumors nearly always occur in the epiphyseal region and may extend to the articular surface of the bone. Campanacci and coworkers10 have attempted to grade giant cell tumors according to radiographic criteria; thus, grade 1 lesions are radiographically indolent, and grade 3 tumors are radiographically aggressive. Unfortunately, the majority of giant cell tumors are probably what Campanacci and colleagues refer to as grade 2, in which the radiographic appearance is aggressive but the tumor has not yet broken through cortical bone. Radiographic grading may be important in helping the surgeon decide on the appropriate treatment.

Grossly, the tumor consists of a red, soft tissue that typically extends up the subchondral bone at the articular surface. Microscopically, a giant cell tumor shows a combination of giant cells and mononuclear cells, with a more or less uniform distribution of the giant cells. Giant cell tumors that appear to be more aggressive histologically do not necessarily behave more aggressively clinically.17

The extent of surgery required to eradicate giant cell tumors is somewhat controversial. In the region of the elbow, particularly difficult problems may be encountered. The distal end of the humerus does not lend itself well to surgical excision by curettage unless the lesion is radiographically a grade 1 lesion. Total excision of the distal end of the humerus, although it would probably be curative and prevent local recurrence, creates a very serious problem for the reconstructive surgeon. Allograft replacement might be considered in this setting, but the decision about the method of treatment is often exceedingly difficult. Excision by curettage in other locations results in a local recurrence rate of approximately 25%. It is probably reasonable to accept this risk and to try curettage for the first treatment because the alternative of resection of the distal end of the humerus is so drastic (Fig. 82-7). However, if the tumor has already broken through the cortex into the surrounding soft structures, curettage is unlikely to be effective. For tumors of the proximal end of the ulna, curettage might be more reasonable because there is more bone to work with; hence, a larger margin of normal bone can be included in the resected specimen, whether resection is done by curettage or actual excision. Whenever possible, the treatment of choice is to pack the tumor cavity with methylmethacrylate (Fig. 82-8). This method of reconstruction has, in other locations, proved to be effective. If the proximal radial head is involved with a reasonably small tumor, it is probably best treated with simple excision.28,32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree