12 Neck and cervical spine

The commonest orthopaedic cause of neck disorders is degeneration of a cervical intervertebral disc. This may lead to protrusion of part of the disc contents (prolapsed cervical disc) or, more often, it may give rise to secondary osteoarthritic changes in the intervertebral joints (cervical spondylosis). These conditions together make up a large proportion of the disabilities of the neck encountered in an orthopaedic out-patient department. Another major cause of prolonged pain and stiffness of the neck is the common post-traumatic musculo-ligamentous strain known generally as whiplash injury.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF NECK COMPLAINTS

EXPOSURE

The patient must be stripped to the waist. Preferably he should stand, or he may sit upon a stool.

STEPS IN CLINICAL EXAMINATION

A suggested routine for clinical examination of the neck is summarised in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the neck

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF NECK, WITH NEUROLOGICAL AND VASCULAR SURVEY OF UPPER LIMBS | |

| Inspection | Movements |

| Bone contours: ?deformity | Flexion–extension |

| Soft-tissue contours | Lateral flexion |

| Colour and texture of skin | Rotation |

| Scars or sinuses | ? Pain on movement |

| Palpation | ? Crepitation on movement |

| Skin temperature | Neurological state of upper limb |

| Bone contours | Muscular system |

| Soft-tissue contours | Sensory system |

| Local tenderness | Sweating |

| Vascular state of upper limb | Reflexes |

| Colour | |

| Temperature | |

| Pulses | |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF NECK SYMPTOMS | |

| Symptoms suggestive of a neck disorder may arise from the ears or throat. Symptoms in the upper limb suggesting a neck disorder with involvement of the brachial plexus may arise from shoulder, elbow, or nerve trunks in their peripheral course | |

| 3. GENERAL EXAMINATION | |

| General survey of other parts of the body. Neck symptoms may be only one manifestation of a more widespread disease | |

DEFORMITY

The cervical spine normally has a slight anterior curvature (lordosis). Straightening of this curve, or an angulation in the reverse direction (kyphosis), is sometimes significant and may suggest an underlying abnormality. Any lateral or rotational deformity (torticollis) must also be noted.

MOVEMENTS

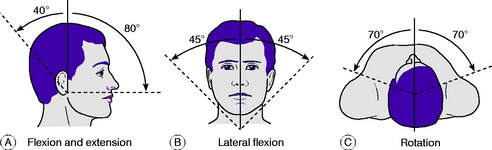

The movements to be examined are flexion, extension, lateral flexion to right and left, and rotation to right and left (Fig. 12.1). Flexion–extension movements occur mainly at the occipito-atlantoid joint but to some extent throughout the cervical spine. Lateral flexion takes place throughout the cervical spine. Rotation occurs largely at the atlanto-axial joint, with a small range of movement at the other joints. It is important to find out whether movement causes pain and, if so, whether the pain is felt locally in the neck or whether it is referred down the upper limbs. It should be noted also whether movement is accompanied by audible or palpable crepitation.

NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF UPPER LIMBS

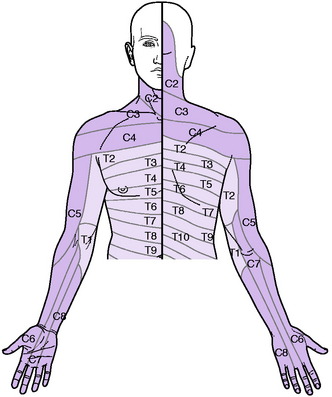

Sensory system. Examine the patient’s sensibility to touch and pin prick. In appropriate cases test also the sensibility to deep stimuli, joint position, vibration, and heat and cold. The nerve roots supplying the sensory dermatomes in the upper limb are shown in Fig. 12.2. In the assessment of sensory loss it should be remembered that the middle or long finger, representing the central axis of the limb, is innervated mainly from the seventh cervical nerve. The radial half of the hand is innervated by the proximal roots of the brachial plexus (C5, C6) whereas the ulnar half is innervated from the more distal roots (C8, T1).

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Radiographic examination. Routine radiographs of the cervical spine include an antero-posterior and a lateral projection. Additional projections are often required when it is desired to show a particular structure more clearly. For a study of the dens (odontoid process) of the axis a special antero-posterior projection is made through the open mouth. Occasionally oblique projections are required for a proper investigation of the intervertebral foramina and the facet joints, and is also valuable in revealing the size and shape of a cervical rib.

DEFORMITIES AND CERVICAL INSTABILITIES

INFANTILE TORTICOLLIS (‘Congenital’ torticollis; muscular torticollis)

In infantile torticollis (wry neck) the head is tilted and rotated by contracture of the sternomastoid muscle of one side. Strictly this is not a true congenital deformity because it arises after birth. With improvements in obstetrical practice it is now seen much less often than it was in the past.

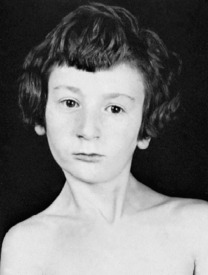

Clinical features. The child, often between 6 months and 3 years old when brought for consultation, is noticed to hold the head on one side. On examination, the contracted sternomastoid muscle is felt as a tight cord. The ear on the affected side is approximated to the corresponding shoulder. In long-established cases there is retarded development of the face on the affected side, with consequent asymmetry (Fig. 12.3).

Fig. 12.3 Infantile torticollis. Note the tense cord-like left sternomastoid muscle and the facial asymmetry.

CONGENITAL SHORT NECK (Klippel–Feil syndrome)

The degree of abnormality varies widely. The bony deformity consists in fusion of two or more of the cervical vertebrae. Clinically, the neck appears short or absent, and the hair-line is low. The neck may also be webbed to the shoulder. Movements of the head are restricted. Radiographs show the underlying bony abnormality, but operation is seldom indicated.

CERVICAL SUBLUXATION AND DISLOCATION (Spontaneous subluxation of the cervical spine; cervical spondylolisthesis)

Causes and pathology. There are three types, caused by:

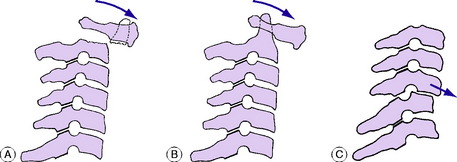

Congenital or acquired non-fusion of dens. Occasionally the dens fails to fuse with the body of the axis by bone, being attached only by fibrous tissue (os odontoideum). Under the constant stress of superimposed weight the fibrous bond slowly stretches, allowing the dens, and with it the atlas and skull, to slide gradually forwards upon the axis (Fig. 12.4A). A similar condition may exist after fracture of the dens, but this would be preceded by a history of trauma. Instability may also be present in patients with Down’s syndrome and radiological screening may be indicated in patients with this condition.

Inflammatory softening of the transverse ligament of the atlas. In this type the underlying cause is an inflammatory lesion in the upper part of the neck, such as rheumatoid arthritis or a severe local infection of the throat or glands. There is rarefaction of the atlas, with softening of the transverse ligament. In consequence the atlas is able to slide forwards upon the axis (Fig. 12.4B).

Instability from previous injury or from arthritis. A traumatic fracture- dislocation or subluxation at any level in the cervical spine may cause permanent instability, with a liability to slow redisplacement months or years after the initial injury (Fig. 12.4C).

Clinical features. In the inflammatory type there is complaint of ‘stiff neck’. The head is held rigidly, the cervical muscles being in spasm. In subluxation from congenital or post-traumatic instability there are discomfort and stiffness in the neck, and flexion deformity is apparent. Radiographs will show the displacement, its level and its type (Fig. 12.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree