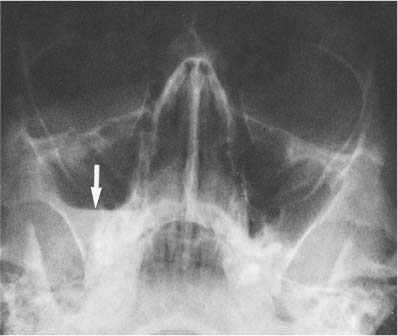

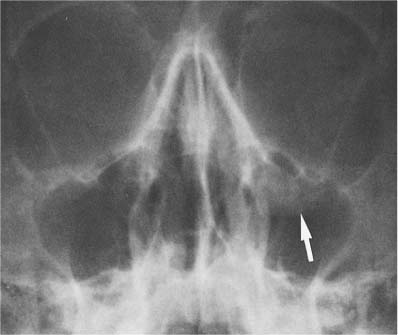

10 Nasal Fossa and Paranasal Sinuses The paranasal sinuses consist of the frontal sinus, sphenoid sinus, maxillary antra, and ethmoidal air cells. They communicate with the nasal fossa and are lined with a mucous membrane contiguous with that of the nasal cavity. These are two important factors for the understanding of the development and spread of any pathologic process. Pneumatization and expansion of the sinuses occurs during the first and second decade of life, reaching its full extent only in early adulthood. The size of the sinuses varies greatly from individual to individual and even between the right and left side of the same individual. Unilateral or bilateral hypoplasia is not uncommon and has no clinical significance, except in some congenital syndromes where it might be a finding in a much wider spectrum of radiographic abnormalities (e.g., hypoplastic maxillary antra in dysostosis cleidocranialis). Enlarged paranasal sinuses are a constant feature of acromegaly, but as an isolated finding are best disregarded. Since the paranasal sinuses are air-containing cavities, soft-tissue changes occurring in them can already be well demonstrated by conventional radiographic technique. Complete opacification of a sinus may at times be more difficult to appreciate than less severe mucosal thickening that is still contrasted by air. As a rule of thumb, the maxillary antra should normally have a similar transparency as the orbits in the Water’s view. Fluid accumulation in a paranasal sinus can easily be demonstrated using a horizontal roentgen beam. In this case the fluid will accumulate in the deepest part of the sinus and form a sharp interface with the air topping it. It must, however, be remembered that when using a vertical beam, any fluid accumulation in a sinus produces a diffuse loss of translucency that is indistinguishable from mucosal thickening. An air—fluid level in a sinus is caused by the accumulation of blood, pus, or exudate produced by the mucosa. An air—fluid level produced by blood is most commonly the result of a fracture (Fig. 10.1). Occasionally the only radiographic clue to a paranasal sinus fracture consists of a localized soft-tissue swelling caused by mucosal or submucosal bleeding. This is particularly common in blow-out fractures of the orbit, presenting as a small, soft-tissue bulge on the antral roof (Fig. 10.2). A more extensive hemorrhage can cause a complete loss of translucency of the involved paranasal sinus. In the maxillary antrum, a soft-tissue hematoma of the overlying cheek must be differentiated from a hemorrhage within the sinus, since both can cause a generalized loss of translucency. Clinical examination of the patient and radiographs in different projections allow differentiation between these two conditions. Fractures of the paranasal sinus can sometimes only be diagnosed radiographically by demonstrating the leak of air from a sinus into a neighboring structure. Orbital emphysema is encountered with maxillary and ethmoidal sinus fractures (see Fig. 9.2). Air within the cranial cavity (pneumocephalus) may result from a fracture involving the frontal or ethmoid sinus. Acute sinusitis is the most common cause of an air—fluid level in a paranasal sinus. Although air—fluid levels occur with allergic sinusitis, they are more common with infectious sinusitis. The latter condition is often limited to one sinus, and mucosal thickening paralleling the bony walls is characteristically found. In allergic sinusitis a diffuse involvement of the nose (swelling of the turbinates) and all sinuses is usually present. In this condition, the mucosal thickening often produces a scalloped lining, and polyp formations are frequently encountered. Fig. 10.1 Air-fluid (blood) level secondary to trauma. A fracture in the right antral roof with bleeding into the right maxillary antrum evident by the air-fluid level (arrow) is seen. Fig. 10.2 Blow-out fracture of the left orbit. A polypoid soft-tissue mass (arrow) hanging from the left antral roof is the only radiographic evidence of this fracture. A soft-tissue thickening or mass with or without destruction of the adjacent bone can, however, be found in many other conditions, which will be discussed in Table 10.1. Asymmetry of the sinuses between the right and left side or localized osteosclerosis in a sinus wall can also produce a unilateral decrease in translucency that should not be confused with soft-tissue thickening within a sinus (Fig. 10.3). Benign and malignant tumors of cartilagenous or osseous origin may occasionally develop in the facial bones. Their presentation, however, does not differ from any other location and their differential diagnosis has been covered in Chapter 5. A rhinolith in the nasal cavity should not be mistaken for such a lesion (Fig. 10.4). Table 10.1 Soft-tissue Thickening or Mass in Paranasal Sinuses

Lesion | Radiographic Appearance | Comments |

Benign tumors (see Fig. 10.18) | Variable, ranging from a localized soft-tissue mass to a dense bony lesion (osteoma). | Except for osteomas, these tumors are very rare and include lipomas, hemangiomas, dermoids and chondromas. |

Carcinoma (Figs. 10.5 and 10.6) | Soft-tissue mass associated almost invariably with bone destruction. Sclerotic reaction of infiltrated bone occurs on rare occasions. | Usually found in patients over 50. Squamous cell carcinoma is by far the most common histologic type. |

Sarcoma | Findings indistinguishable from carcinoma except when new bone is formed (e.g., osteosarcoma). | Rare. All ages. Benign mesenchymal neoplasms are even less common. |