Multidirectional and Posterior Shoulder Instability

Alan S. Curtis

Suzanne L. Miller

Aaron Gardiner

KEY POINTS

Posterior and multidirectional instability represent a spectrum of disease encompassing posterior instability with dislocation, posterior unidirectional instability with recurrent posterior subluxation, bidirectional instability with posterior and inferior subluxation, and multidirectional instability with global laxity.

Nonoperative approaches are the mainstay of treatment for most cases.

History and physical examination, especially examination under anesthesia, are critical to selecting the proper diagnosis and treatment, as imaging studies are often nondiagnostic.

Arthroscopic approaches allow a thorough evaluation of intra-articular pathology and a pathology-specific treatment approach.

Arthroscopic treatment allows the surgeon to address labral tears, capsular laxity, capsular tears, and the rotator interval.

Open procedures may be preferred in cases of bone loss and in certain revision cases.

Posterior and multidirectional shoulder instability represent a spectrum of disease from posterior instability with dislocation to posterior unidirectional instability with recurrent posterior subluxation, bidirectional instability with posterior and inferior laxity, and multidirectional instability with global laxity. Posterior instability is uncommon, representing approximately 5% of all glenohumeral instability. However, more subtle cases of posterior subluxation or multidirectional instability are likely often undiagnosed. Classically, these patterns of instability have been treated with an open surgical approach (1). However, arthroscopic techniques have progressed to the point where they are an excellent option for treating these conditions. This chapter will review the diagnosis and treatment of posterior and multidirectional instability with an emphasis on arthroscopic surgical techniques.

POSTERIOR INSTABILITY

Clinical Evaluation

Pertinent History

Acute posterior dislocation is a rare event, much less common than anterior dislocation. Many times the dislocation is self-reduced immediately or shortly after the event. A history of seizures or electrocution should alert the clinician to the possibility of posterior dislocation secondary to the severe muscular contractions which occur in these conditions. Acute posterior dislocations are often missed in the emergency department as anterior-posterior (AP) radiographs may look relatively normal to the unsuspecting eye and patients will be relatively comfortable in a sling with the arm internally rotated. There is a delay in diagnosis in many cases of posterior dislocation, leading to delayed diagnosis in a larger percentage of chronic dislocations in comparison with anterior dislocations (2). In these cases, any history of seizures or alcohol abuse should be elicited.

Physical Examination

The most dramatic finding with a posterior dislocation is the severe limitation of external rotation. Most patients will have a range of motion limited to approximately 90° of forward flexion and external rotation to neutral. Many patients find the sling position tolerable while dislocated. A careful neurologic and vascular examination should be performed both before and after any reduction attempts.

Imaging

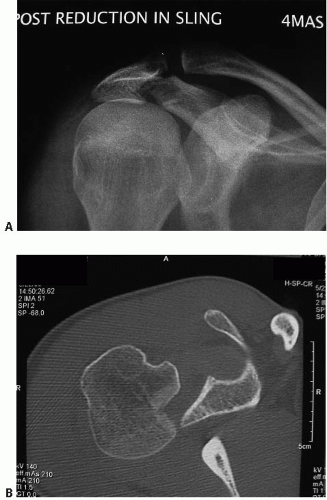

Plain X-rays are generally sufficient to make the diagnosis. Three orthogonal views, consisting of AP, outlet, and axillary views, should be obtained in all cases. Poor quality or inadequate X-rays are the most common cause of a missed diagnosis. Axial imaging with a CT scan is very helpful to assess any bone impaction or defects as well as in cases where adequate axillary X-rays cannot be obtained (Fig. 18.1).

FIGURE 18.1. A: Postreduction radiograph of a right shoulder obtained in the emergency department. B: CT scan of the same patient showing a posterior dislocation. |

Treatment

Acute Dislocation

Treatment of acute posterior dislocation is generally nonoperative. Closed reduction is generally successful in the emergency department with sedation. An external rotation or “gunslinger” brace is often useful immediately after reduction. A small impaction defect in the humeral head (greater than 20%) generally will not need operative treatment. In these cases, operative treatment is reserved for patients with dislocations not reducible with closed means or for cases with recurrent instability.

Missed or Chronic Dislocation

Treatment of missed or chronic posterior dislocations is difficult and often requires open surgical techniques (2). A thorough examination of this topic is beyond the scope of this chapter. In general, relatively acute dislocations (greater than 6 months) with smaller impaction defects (approximately 20% to 40% of the humeral head) may be treated with an open reduction and a repair of the pathology present. This may consist of an allograft to the humeral head or a partial arthroplasty to fill the defect. A McLaughlin procedure, consisting of transfer of the lesser tuberosity to the humeral head defect, may also be performed. More chronic dislocations and larger bone defects are often best treated with arthroplasty. In rare cases, such as in patients with high surgical risk and minimal symptoms, the preferred course of action may be to treat chronic dislocations nonoperatively.

RECURRENT POSTERIOR SUBLUXATION AND MULTIDIRECTIONAL INSTABILITY

Clinical Evaluation

History

Recurrent posterior subluxation is more common than posterior dislocation. In many cases, this condition is the sequela of a traumatic event or of repetitive trauma. This is often the case in football players or weightlifters. Classically, patients will sustain contact with the arm outstretched in front of their body or will fall on an outstretched hand. Cases without a history of trauma are also common. This is often the case in athletes who perform overhead activities who have underlying capsular laxity such as swimmers, gymnasts, or volleyball players.

With multidirectional instability, patients usually present with a complaint of pain in the affected shoulder. Patient age typically ranges from teenage to middle age. In some cases, patients will report a history of a subluxation or dislocation, often with spontaneous reduction. Symptoms often present gradually, however, with no traumatic inciting event. Repetitive microtrauma may lead to symptomatic instability such as in competitive swimmers and volleyball players. The activities and arm positions that lead to symptoms should be elucidated. Also, the level of activity during which instability occurs should be determined. For example, symptoms may only occur during the overhead activity of spiking a volleyball or may occur while carrying light objects with the arms at the patient’s side. Occasionally, patients may report neurologic symptoms in the affected arm, which may be due to the inferiorly subluxing humeral head stretching the brachial plexus. A history of connective tissue disorders should be sought. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan’s syndrome may have a predisposition for increased joint laxity and instability.

It is essential to differentiate between laxity and instability. Patients have varying degrees of laxity, which is often asymptomatic. Instability is laxity that is causing dysfunction. With multidirectional instability, the patient may often report varying levels of symptoms in both shoulders. This, especially in cases without a history of significant trauma, is consistent with the generalized capsular laxity that can be present with multidirectional instability.

Classification

Classification of instability is usually by the direction of the instability. Patients may have unidirectional instability (anterior or posterior), bidirectional instability (anterior

or posterior and inferior), or multidirectional instability. Patients may also be classified by their mode of instability, which may be involuntary, positional, or voluntary. Patients with involuntary instability are unable to demonstrate their instability in the office. Their instability is usually elicited by trauma, often during their sport of choice. Patients with positional instability are able to demonstrate their instability in the office by positioning their shoulder appropriately. However, this causes discomfort to the patient and the patient generally goes to great lengths to avoid this position of instability during their daily activities and during sports. Patients with voluntary instability are able to demonstrate their instability at will in the office, often with little or no discomfort. These cases should be approached with caution. Often the instability is either habitual or associated with secondary gain. Surgery should be avoided in these cases.

or posterior and inferior), or multidirectional instability. Patients may also be classified by their mode of instability, which may be involuntary, positional, or voluntary. Patients with involuntary instability are unable to demonstrate their instability in the office. Their instability is usually elicited by trauma, often during their sport of choice. Patients with positional instability are able to demonstrate their instability in the office by positioning their shoulder appropriately. However, this causes discomfort to the patient and the patient generally goes to great lengths to avoid this position of instability during their daily activities and during sports. Patients with voluntary instability are able to demonstrate their instability at will in the office, often with little or no discomfort. These cases should be approached with caution. Often the instability is either habitual or associated with secondary gain. Surgery should be avoided in these cases.

Physical Examination

Physical examination should begin with a visual inspection of the affected shoulder to evaluate for any skin changes, swelling, or atrophy. Palpation can identify any localized areas of tenderness. A thorough examination should be performed to exclude other causes of shoulder pain such as cervical spine pathology, and complete peripheral neurologic and vascular exams should be performed. Active and passive range of motion should be determined and compared with the unaffected side. Muscle strength should also be documented as many patients with multidirectional instability can have some degree of weakness from neurologic injury.

The scapula is often overlooked during shoulder examination. The scapula has a large arc of motion on the thoracic wall, which allows the glenoid to maintain an efficient link to the humeral head during athletic activity. Scapular winging may be present in association with instability. In these cases, the winging is often secondary, and due to pain and inhibition of the scapular stabilizers. Primary scapular winging due to long thoracic or spinal accessory nerve palsy is rare but should be excluded.

Several specialized tests exist to evaluate instability and determine the direction of instability. The sulcus test is used to evaluate inferior instability. This test is performed by placing an inferiorly directed force on the affected arm with the shoulder adducted. In a positive test, the humeral head is translated inferiorly, leaving a hollow area or “sulcus” between the lateral edge of the acromion and the humeral head. The sulcus test may be performed in both neutral rotation and external rotation. If the sulcus sign decreases or disappears with external rotation, this suggests a competent rotator interval.

Anterior instability is evaluated by the apprehension test and the Jobe relocation test. These examinations are performed with the patient supine on the exam table. The affected shoulder is abducted to 90°, and the shoulder is externally rotated. A positive test produces a sense of impending instability. The Jobe relocation test involves placing a posteriorly directed force on the shoulder while the anterior apprehension test is performed. In cases of anterior instability, this posterior force should relieve the apprehension from abduction and external rotation.

Posterior instability may be evaluated with the jerk test. This may be performed in the sitting or standing position. The shoulder is forward flexed to 90° and internally rotated. The examiner then applies a posteriorly directed force while moving the arm across the body. In a positive test, as the arm is adducted, a “jerk” will be observed as the humeral head subluxes posteriorly out of the glenoid. The test may also be positive when there is a palpable “jerk” when the posteriorly subluxed humeral head reduces back into the glenoid with external rotation of the shoulder.

The load and shift test can be used to evaluate both anterior and posterior instability. This test is performed in the supine position. The shoulder is abducted slightly and an axial load as well as either an anterior or a posterior force is applied. This exam is graded from 1+ to 3+. 1+ is the ability to translate the humeral head to the edge of the glenoid, 2+ is the ability to subluxate the humeral head over the glenoid rim and have it spontaneously reduce, and 3+ is a dislocation that does not spontaneously reduce.

In addition to the previous tests, all patients with suspected multidirectional instability should be evaluated for generalized ligamentous laxity with an examination for elbow, thumb, and metacarpophalangeal joint hyperextension.

Imaging

In cases of recurrent posterior subluxation or multidirectional instability, X-rays and CT scans are usually normal. The CT scan is very useful if there is a small glenoid rim fracture present. If there is any question of bone loss or bone deficit such as in glenoid hypoplasia, then a CT scan is useful for evaluation. CT scans are also useful in revision cases where hardware may be present.

MRI is useful for evaluation of capsule, labral, and other soft tissue pathology. In cases of posterior instability, a posterior Bankart or labral tear may be seen (Fig. 18.2). Capsular injuries such as a reverse humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments (RHAGL lesion) may be seen in cases of posterior instability. MRI may be performed with or without intra-articular contrast. Some authors have reported an increased sensitivity for detecting labral pathology with MR arthrogram compared with conventional MRI. It is important to remember that ultimately the diagnosis of instability is clinical, and many patients, especially those with multidirectional instability, will have normal MRI exams. MRI may still be useful in these cases for excluding other causes of shoulder pain or dysfunction.

Treatment

Many cases of posterior instability and most cases of multidirectional instability are successfully treated nonoperatively (3,4). In almost all cases, nonoperative treatment is the appropriate initial treatment. Nonoperative treatment consists of initial activity modification and formal physical therapy focusing on strengthening and scapular stabilization. Especially in cases of multidirectional instability, a progressive exercise program that gradually strengthens the scapular stabilizers, deltoid, and rotator cuff muscles has been successful in returning patients to normal activity.

Operative treatment is usually reserved for the failure of a thorough course of nonoperative treatment. It is important to assess preoperatively, which patients need to have their pathology addressed with an open surgical technique. This is the case for patients with bone loss that will require bone grafting. Selected revision cases also may be better served by an open surgical approach. A failed arthroscopic stabilization may sometimes be salvaged by an open capsular shift. A failed thermal capsulorrhaphy may also be an indication for open treatment with capsular augmentation.

Arthroscopic treatment of posterior or multidirectional instability consists of a pathology-specific approach that is tailored to the individual patient. After completion of an examination under anesthesia and diagnostic arthroscopy, the entire capsule and labrum as well as rotator interval may be addressed as needed to recreate a balanced capsule and a stable glenohumeral joint. Arthroscopic techniques have been published with excellent success rates, comparable with open techniques for both posterior and multidirectional instability (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree