Monteggia Fracture Dislocations

CASE PRESENTATION

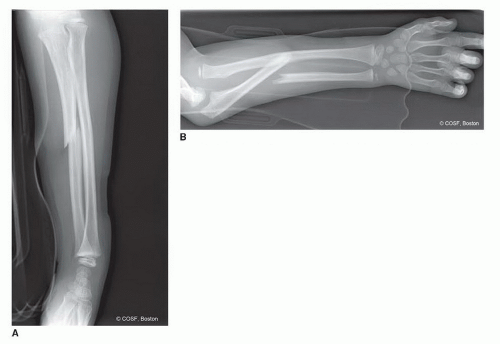

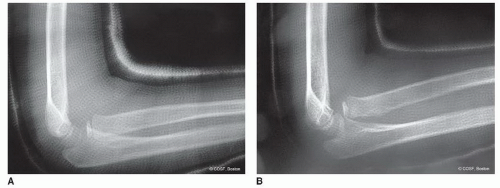

A 6-year-old female presents with mild forearm pain after a fall from a playground swing. She denies any distal numbness, weakness, or tingling. On examination, she has mild swelling and tenderness over her ulna. Initial evaluation includes forearm radiographs shown in Figure 30-1.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

What is a Monteggia fracture dislocation?

How are Monteggia lesions classified?

What are the most common associated injuries?

What are the indications and surgical principles for acute Monteggia injuries?

What are the anticipated outcomes of acute Monteggia care?

What are the potential complications of missed Monteggia lesions?

What are the indications and contraindications for reconstruction of chronic lesions?

What are the principles and surgical techniques for chronic Monteggia reconstruction?

What are the anticipated results and risks of recurrent instability following chronic Monteggia reconstruction?

What are the potential complications of chronic reconstruction?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Despite increased understanding of the epidemiology, clinical presentation, treatment options, and potential complications, Monteggia fracture dislocations remain challenging conditions for the pediatric hand and upper extremity surgeon. In 1943, Sir Watson-Jones wrote that “…no fracture presents so many problems; no injury is beset with greater difficulty; no treatment characterized by more general failure.”1 While these injuries are now treated with greater success than 70 years ago, the complexity and clinical challenges—particularly for chronic Monteggia lesions—persist.

As with any traumatic injury in the child, prompt diagnosis and timely treatment continue to be the keystones for successful Monteggia care. A high index of suspicion combined with appropriate radiographic imaging and sound surgical treatment will result in successful outcomes in the vast majority of acute injuries. Furthermore, despite the discouraging initial results, current strategies for reconstruction of the chronic lesion can lead to successful results in the majority of patients. In treatment of both acute and chronic situations, the principles of restoring ulnar length and alignment, while ensuring radiocapitellar stability, guide surgical care.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Originally described by Giovanni Battista Monteggia in 1814, Monteggia fracture dislocations refer to fractures of the ulna associated with proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) dissociation and radiocapitellar dislocations.2,3 These injuries comprise <1% of all pediatric forearm fractures, typically affecting patients between 4 and 10 years of age. The mechanism of injury is classically described as a fall onto an outstretched hand with forced rotation of the forearm.4 The exact position of the limb and rotational forces imparted will dictate the characteristic patterns of injury.

Clinical Evaluation

One chance is all you need.

—Jesse Owens

Acutely, patients will present with pain and swelling, often but not always, accompanied by forearm deformity and limitations in elbow motion. A thorough neurovascular examination is critical, as 10% to 20% of patients may exhibit a neurologic deficit at presentation, most commonly involving the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN).5, 6, 7, 8 and 9

The diagnosis is made radiographically. Isolated views of the ulna fracture are not sufficient; full-length anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the forearm, including the elbow and wrist, are needed (Figure 30-1).

Substandard or insufficient radiographic evaluation should not be accepted. The tenet that the adjacent joints (above and below) should be assessed in any long bone fracture should be followed. Meticulous attention to radiocapitellar alignment in all views is mandatory.

Substandard or insufficient radiographic evaluation should not be accepted. The tenet that the adjacent joints (above and below) should be assessed in any long bone fracture should be followed. Meticulous attention to radiocapitellar alignment in all views is mandatory.

Unfortunately, despite the increased awareness and understanding of Monteggia fracture dislocations, the initial diagnosis is often missed, resulting in late presentation, challenging surgical reconstruction, and suboptimal outcomes. A number of published reports have documented a relatively high incidence of missed diagnoses.5,10,11 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is paramount, and the adjacent joints should be carefully inspected with any single bone fracture of the forearm.

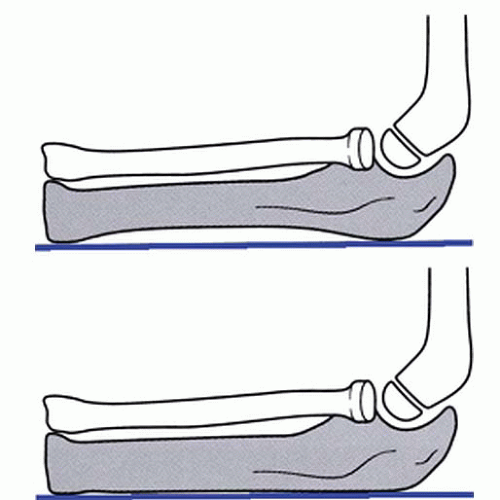

Normally, the longitudinal axis of the radius should bisect the capitellar ossification center on all radiographic views.12,13 Cases of presumed “isolated” radial head dislocations must be scrutinized for abnormal ulnar bowing or plastic deformation; indeed >0.1-mm deviation from a straight ulnar border should alert the treating provider to a possible occult ulnar injury (Figure 30-2).14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 There are some situations where plain radiographs are concerning but equivocal; in these cases, fluoroscopic imaging and/or advanced imaging in the form of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound may be useful to confirm or rule out a congruent radiocapitellar and proximal radioulnar joint reduction.

While congenital radial head dislocations may occasionally present as acute injuries, the presence of a hypoplastic capitellum and convex radial head will usually confirm the diagnosis.19 Furthermore, it is important to note that statistically, most traumatic Monteggia lesions result in anterior radial head dislocation, whereas most (but not all) congenital radial head dislocations are posterior.20, 21 and 22

An understanding of the pathoanatomy of Monteggia fracture dislocations is critical in providing appropriate treatment. In the majority of cases, the annular and quadrate ligaments are disrupted at the PRUJ; however, much of the interosseous membrane between the radius and ulna remains intact, as does the triangular fibrocartilage complex. Anatomic reduction of the ulna, therefore, will often restore PRUJ and radiocapitellar joint congruity. For this reason, treatment is predicated on the nature of the ulna fracture. In addition, the biceps, anconeus, and long forearm flexors exert deforming forces on the proximal radius and ulna, contributing to radial head dislocation, ulnar shortening, and apex radial angulation. Reversing or counteracting these forces is important during fracture manipulation and closed treatment.

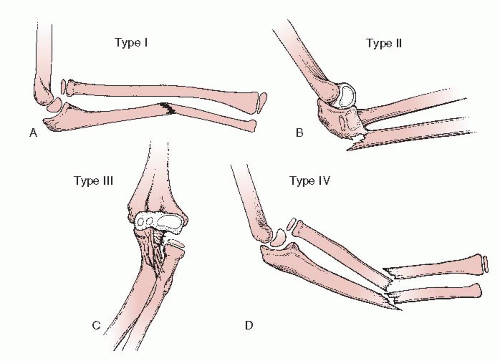

Historically, the Bado classification, based upon the direction of the radial head dislocation and apex of the associated ulnar fracture, has been utilized to describe these injuries (Figure 30-3).2 This classification scheme may aid both in describing the pattern of injury and guiding closed fracture care.

Bado type I injuries refer to anterior dislocation and angulation and are the most common patterns, representing

approximately 70% to 75% of all injuries. The mechanism of injury is thought to be due to a hyperextension injury combined with forearm pronation. Reduction, therefore, involves longitudinal traction, supination, posteriorly directed pressure over the radial head, and flexion of the elbow to 110 or 120 degrees to minimize the deforming effect of the biceps.

approximately 70% to 75% of all injuries. The mechanism of injury is thought to be due to a hyperextension injury combined with forearm pronation. Reduction, therefore, involves longitudinal traction, supination, posteriorly directed pressure over the radial head, and flexion of the elbow to 110 or 120 degrees to minimize the deforming effect of the biceps.

Bado type II injuries refer to posterior radial head dislocations with apex dorsal ulnar fractures. While common in adults, these injuries are relatively rare in children, accounting for 3% to 6% of pediatric Monteggia lesions. Thought to be caused by an axial load on a partially flexed elbow or direct blow to the proximal supinated forearm, the reduction maneuver involves longitudinal traction with the elbow flexed combined with an anteriorly directed force over the radial head.2,7,23,24 There is a propensity for instability with the elbow flexed.

Bado type III injuries refer to lateral dislocations and varus fractures of the proximal ulna. Representing the second most common pattern in children, these too result from hyperextension and pronation with varus stress.25,26 Among the various patterns, it is the Bado type III lesion that is most commonly associated with PIN palsies.27, 28 and 29 Combined longitudinal traction, elbow extension, and valgus stress will serve to reduce the deformity. The need for open reduction is common.25, 26, 27 and 28,30,31

Bado type IV lesions refer to radial head dislocations with fractures of both the radius and ulna. The fractures are typically mid-diaphyseal, with the radial fracture more distal than the ulnar fracture.32 With similar mechanisms of injury as Bado type I injuries, these tend to be higher energy in nature and follow similar treatment principles.

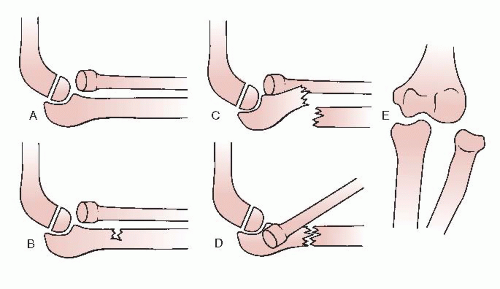

Letts et al.33 have described an alternative classification scheme based upon the pattern of ulnar fracture (Figure 30-4). This classification is helpful in surgical decision making.

The clinical presentation of missed or chronic Monteggia fracture dislocations is quite varied. Many patients will present weeks after injury, when during the course of cast treatment for an “isolated” ulna fracture, the radial head dislocation is noticed (see Sidebar). While distressing, the opportunity to effectuate meaningful restoration

of anatomy and functional potential remains great, as no secondary joint changes have occurred. Other patients will present months to years after injury, either with incidental radiographic diagnosis or for evaluation of new pain, noticeable loss of elbow flexion or forearm rotation, or with apparent deformity (e.g., a palpable radial head in the antecubital fossa or posterolateral elbow, progressive cubitus valgus). For many patients, there will be objective, but often minimally symptomatic, functional loss. Radiographs again confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment.

of anatomy and functional potential remains great, as no secondary joint changes have occurred. Other patients will present months to years after injury, either with incidental radiographic diagnosis or for evaluation of new pain, noticeable loss of elbow flexion or forearm rotation, or with apparent deformity (e.g., a palpable radial head in the antecubital fossa or posterolateral elbow, progressive cubitus valgus). For many patients, there will be objective, but often minimally symptomatic, functional loss. Radiographs again confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment.

Surgical Indications

Set it and forget it.

—Ron Popeil

While all acute Monteggia fracture dislocations merit formal reduction, there are different methods by which this may be achieved. Closed reduction and cast immobilization alone has been advocated by many and is effective for plastic deformation and incomplete fractures, provided they are recognized acutely. However, simple closed reduction alone has a number of disadvantages. First, there is a high risk of recurrent instability due to loss of reduction with cast immobilization alone (Figure 30-5). This is further compounded by the challenges in serial radiographic evaluation of the quality of reduction while the limb is casted, particularly for Bado type III injuries, which require AP views to assess for lateral displacement of the radial head. Furthermore, effective immobilization of displaced Monteggia lesions often requires positioning the acutely injured, swollen limb in extreme positions. For the common Bado type I injuries, for example, hyperflexion is recommended, which may lead to issues with skin integrity and neurovascular compromise. For these reasons, among others, we advocate surgical reduction and stabilization of all acute Monteggia fracture dislocations with complete ulnar fractures.28,34

Chronic Monteggia lesions present a host of different challenges, due to the complexity of surgical steps needed to simultaneously reestablish a stable and mobile PRUJ and potential complications of operative treatment. This is further clouded by the paucity of long-term information regarding the natural history of unreduced Monteggia fracture dislocations.35, 36 and 37 It is known, however, that some patients with missed Monteggia lesions will develop pain, functionally limited loss of elbow motion, cubitus valgus, ulnar or posterior interosseous neuropathy, and/or arthrosis.14,20,22,26,38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree