Modified Brostrom and Brostrom-Evans Procedures

Paul J. Hecht

Justin S. Cummins

Dean C. Taylor

Mark E. Easley

DEFINITION

Lateral ankle injuries are among the most common musculoskeletal injuries in the athletic population.

Rates as high as 7 per 1000 person-years have been reported in the general population.

From 10% to 20% of sprains progress to some kind of chronic symptoms.

Determining whether the patient’s instability is functional (ie, subjective giving way) or mechanical (ie, motion beyond the normal physiologic limits) is important for formulating treatment recommendations.

ANATOMY

The lateral ankle ligament complex consists of the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), and posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL).

The ATFL originates from the anterior aspect of the distal fibula and inserts on the lateral aspect of the talar neck. It is often ill defined and, in the chronically sprained ankle, may be manifest as a capsular expansion.

The ATFL limits anterior translation of the talus with the ankle in neutral and becomes the primary restraint to inversion when the ankle is plantarflexed.

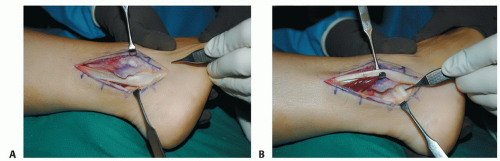

The CFL originates from the distal tip of the fibula and inserts on the lateral wall of the calcaneus (FIG 1A,B).

The CFL measures 4 to 6 mm in diameter and 13 mm in length and is directed posteriorly 10 to 45 degrees from the tip of the fibula.

The CFL functions to resist inversion with the ankle in neutral.

The anterior margin of the talus is wider than the posterior margin, which makes the ankle more susceptible to inversion injuries while in plantarflexion.

The peroneal tendons provide dynamic stability to the ankle joint.

PATHOGENESIS

An inversion force with the ankle in plantarflexion is the most common mechanism of injury.

The ATFL typically is the first ligament injured, followed by the CFL.

Ligament ruptures are most commonly midsubstance tears or avulsions off of the talus.

NATURAL HISTORY

Despite a relatively high incidence of lateral ankle injuries, most patients do well with nonoperative management.

Patients are at increased risk for recurrent lateral ankle sprains after sustaining the initial injury and failing to rehabilitate completely.

Chronic lateral instability may lead to progressive loss of function and osteoarthritic changes of the ankle.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with chronic ankle instability frequently present with pain as well as complaints of multiple sprains caused by minor provocation.

Duration of symptoms, the type of incidents that cause sprains, the need for functional bracing, and previous treatments are important for determining treatment recommendations.

If pain is present between episodes of instability, other lesions about the ankle should also be considered.

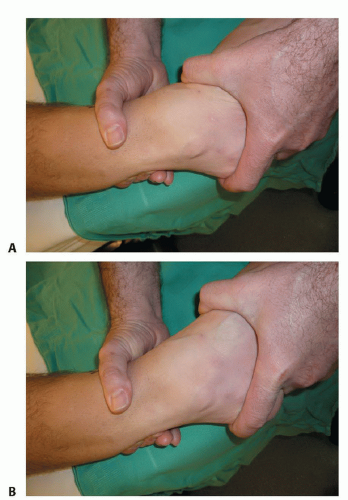

An anterior drawer test with a bony end point that is distinctly different from that of the contralateral ankle is considered markedly positive.

Physical examination techniques include the following:

Palpation. Palpate the ATFL, CFL, syndesmosis, medial and lateral malleoli, peroneal tendons, base of the fifth metatarsal, and anterior process of the calcaneus.

Anterior drawer test (FIG 2A,B). The ankle is held in plantarflexion, and the talus is translated forward relative to the tibia. With intact medial structures, the displacement is rotatory. Translation of 5 mm more than the contralateral ankle or absolute translation of 9 to 10 mm is a positive test and suggests an incompetent ATFL. Grading ATFL injuries: I, stretching; II, partial tearing; III, complete rupture; most useful in the acute setting to determine which structures are injured.

Talar tilt. The heel is inverted with the ankle in neutral. Range of motion is compared to the contralateral ankle. Increased inversion is suggestive of a CFL injury.

Alignment. Assess the standing alignment of the hindfoot. Varus hindfoot alignment predisposes the ankle to inversion injury.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard radiographs should include standing anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and mortise views to evaluate for anterior tibial marginal osteophytes, talar exostoses, osteochondral lesions of the talus, or intra-articular loose bodies.

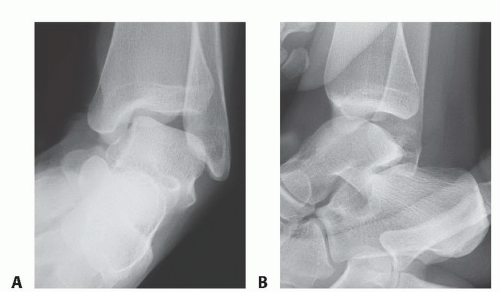

Talar tilt can be assessed with inversion stress mortise views of the ankle (FIG 3A).

Comparison views of the contralateral ankle should also be obtained.

A talar tilt angle greater than 10 degrees, or 5 degrees greater than the contralateral ankle, is considered pathologic laxity.

Anterior translation stress radiographs can be obtained by performing the anterior drawer test and shooting a lateral radiograph (FIG 3B).

Comparison stress views of the contralateral ankle should also be obtained.

Anterior translation 5 mm greater than the contralateral ankle, or an absolute value of greater than 9 mm, is suggestive of instability.

Stress radiographs may be helpful, but physical examination remains the gold standard for evaluation of instability.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful to evaluate the ligamentous injury as well as peroneal tendon pathology and suspected osteochondral injuries.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Lateral process talar fracture

Anterior process calcaneus fracture

Base of the fifth metatarsal fracture

Tarsal coalition

Osteochondral lesion of the talus or tibia

Subtalar instability

Syndesmosis injury

Neurapraxia of the superficial peroneal or sural nerve

Peroneal tendon tear

Peroneal instability

Sinus tarsi syndrome

Anterolateral ankle soft tissue impingement

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Physical therapy should be the initial treatment for patients with chronic instability.

Proprioceptive training and peroneal tendon strengthening are the most important features.

The duration of therapy varies based on strength deficiencies and the intensity of the program.

External stabilization of the ankle with taping or bracing can be effective.

Taping provides tibiotalar stability, but quickly deteriorates with activity.

Reusable braces provide similar stability, but do not lose effectiveness with activity.

Orthotic devices and shoe wear modification can also be used when foot or ankle malalignment contributes to the instability.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

If the patient fails 3 to 6 months of conservative treatment and has persistent signs and symptoms of functional and mechanical instability, he or she becomes a candidate for the modified Brostrom procedure or the modified Brostrom-Evans procedure, which is a combination of the modified Brostrom procedure and the Evans procedure, in which the anterior 50% of the peroneus brevis (PR) is tenodesed to the fibula.

Indications for the Brostrom-Evans procedure

Athlete or patient in whom greater restraint against inversion is desired, such as football lineman who does not need as much hindfoot flexibility as a running back

Anatomic repair planned but greater than anticipated instability, particularly with inversion stress, and an intraoperative determination that more restraint to inversion is needed than can be afforded by the modified Brostrom procedure alone

Lateral ankle instability in a patient with preexisting longitudinal split tear of the PR

Preoperative Planning

The history must be considered. A relative contraindication for this anatomic repair is generalized ligamentous laxity as might be encountered in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Carefully review the physical examination. If a varus heel exists, a Dwyer-type calcaneal osteotomy should be considered.

If an osteochondral lesion is present, the ligamentous reconstruction should be done in conjunction with arthroscopic or open treatment of the osteochondral defect.

Positioning

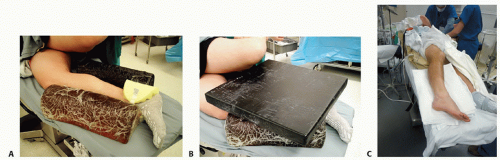

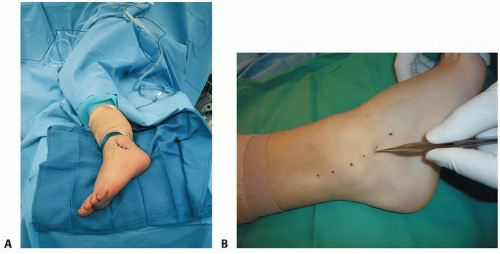

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with appropriate padding at bony prominences to avoid damage to subcutaneous structures (FIG 4A,B).

An operative platform is created using bolsters or blankets.

A “bump” made of four or five towels is used either proximal to the ankle to create a varus or inverted position for better exposure or distal to the ankle to create a valgus or everted position to approximate the edges of the repair (FIG 4C).

Approach

Two commonly used approaches

J incision (FIG 5A)

The incision is made from the distal tip of the fibula along its anterior margin proximally to the level of the ankle mortise.

Does not afford optimal access to the peroneal tendons

Curvilinear extensile exposure (FIG 5B)

Curvilinear incision over posterior tip of fibular, extending to sinus tarsi area

Affords comprehensive exposure to anterior ankle, ATFL, CFL, and peroneal tendons

TECHNIQUES

▪ Modified Brostrom Anatomic Lateral Ankle Ligament Repair with Suture Anchors

Perioperative antibiotics are given.

The patient is positioned as described, a thigh tourniquet is placed, and a standard orthopaedic prep and drape is carried out. The tourniquet is inflated.

The incision is made as described under Approach in the Surgical Management section (TECH FIG 1A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree