Snapping Hip/Lateral Hip

J.W. Thomas Byrd

MaCalus V. Hogan

Brian D. Busconi

Sean McMillan

Craig M. Roberto

Scott King

DEFINITION

Coxa saltans is a term popularized by Allen and various co-authors.1

Encompasses three types

Internal type (iliopsoas tendon)

External type (iliotibial band)

Intra-articular type was originally attributed to diverse intra-articular pathology (ie, loose bodies, labral tears, etc.).

Today, there is more accuracy in the description and diagnosis of intra-articular hip pathology, therefore it is no longer referred to as snapping hip.

ANATOMY

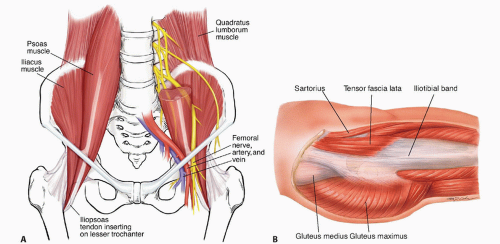

The iliopsoas complex, a powerful hip flexor, is formed from the psoas major and iliacus muscles (FIG 1A).

The psoas major originates from the lumbar transverse processes and the lateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs from T12 to L5; the iliacus originates from the superior two-thirds of the iliac fossa, the sacral ala, and the anterior sacroiliac ligaments.

The tendon forms first from the psoas proximal to the inguinal ligament and then rotates such that its anterior surface comes to lie medial and its posterior surface lateral.

The tendon broadly inserts over the lesser trochanter.

It is joined by an accessory tendon from the iliacus, and the tendons then fuse together before forming the enthesis of the iliopsoas. Some muscle fibers of the iliacus remain separate, attaching directly to bone.

In the sagittal plane, as the iliopsoas exits the pelvis, it is redirected 40 to 45 degrees over the pectineal eminence toward its insertion site.

The iliotibial band and its associated muscles act to flex, abduct, and internally rotate the hip (FIG 1B): The fascia lata covers the entire hip region, encasing its three superficial muscles, that is, the tensor fascia lata, sartorius, and gluteus maximus.

A confluence of the tensor fascia lata and gluteus maximus forms the iliotibial band.

The gluteus maximus also partly inserts into the proximal femur at the gluteal tuberosity.

This fibromuscular sheath was described by Henry12 as the “pelvic deltoid,” reflecting on the fashion in which it covers the hip, much as the deltoid muscle covers the shoulder.

PATHOGENESIS

Internal Type

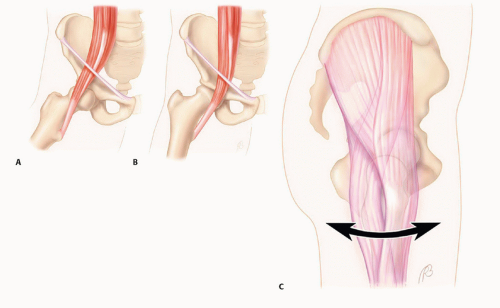

The snapping occurs as the iliopsoas tendon subluxes from lateral to medial while the hip is brought from a flexed, abducted, and externally rotated position into extension with internal rotation (FIG 2A,B).

It has been theorized that the anterior aspect of the femoral head and capsule, the pectineal eminence, the iliopsoas bursa, or some combination of these are responsible for transiently impeding the tendon and creating the snapping.

Incidental, asymptomatic snapping of the iliopsoas tendon is estimated to be present in at least 10% of a normal, active population.5

Painful snapping may be precipitated by macrotrauma or repetitive microtrauma in patients with a predilection for certain activities such as ballet.

The exact structural alteration that occurs when symptomatic snapping develops has not been defined.

External Type

The external snapping hip originates as the iliotibial band snaps over the prominence of the greater trochanter and often is attributed to a thickening of the posterior part of the iliotibial band or anterior border of the gluteus medius (FIG 2C).

The thickened portion lies posterior to the posterior edge of the greater trochanter in extension and slides and snaps into an anterior position as the hip begins to flex.

The greater trochanteric bursa lies between the iliotibial band and greater trochanter. It overlies the tendinous insertion of gluteus medius and vastus lateralis origin. In some instances, it may become inflamed and painful secondary to snapping.

Coxa vara and reduced bi-iliac width have been proposed as predisposing anatomic factors.

Tightness of the iliotibial band also may be an exacerbating factor.

Like snapping of the iliopsoas tendon, snapping of the iliotibial band may be an incidental finding without precipitating cause or symptoms.

Painful snapping may occur following trauma but is more commonly associated with repetitive activities, classically being described in the downhill leg of runners training on a sloped roadside surface.

It also has been reported as an iatrogenic process following surgical procedures that leave the greater trochanter more prominent, or reconstructive procedures around the knee that alter the iliotibial band.

NATURAL HISTORY

For most people, the snapping hip remains asymptomatic, never requiring treatment.

In patients in whom the snapping hip is symptomatic, the course is variable, but there are no apparent long-term consequences of a chronic snapping hip.

Spontaneous resolution may occur but is uncommon.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Iliopsoas Tendon

The history of onset of symptoms is variable and may be insidious, owing to specific repetitive maneuvers or an acute injury.

Symptomatic internal coxa saltans presents with anterior groin pain and associated snapping, which is often audible.

Patients often report snapping with climbing stairs or rising from a chair.

Although the symptoms typically are referred to the anterior groin, some patients may describe flank or sacroiliac discomfort, reflecting irritation around the origin of the psoas and iliacus muscles.

Physical examination is performed with the patient supine, hip flexed greater than 90 degrees, abducted and externally rotated, then passively brought into extension with internal rotation; this recreates the snap.

In some instances, this is a dynamic process that the patient can demonstrate actively better than the examiner can elicit on physical examination. Although often prominent, it may be subtle and may occur more as a sensation experienced by the patient rather than one that the examiner can observe objectively.

Applying pressure over the anterior joint can block the tendon from snapping and assist in confirming the diagnosis.

Iliotibial Band

As with the iliopsoas tendon, patients may describe the onset of symptoms as being insidious due to specific repetitive activities or in response to acute trauma.

Whereas snapping of the iliopsoas tendon often can be heard from across the room, snapping of the iliotibial band can be seen from across the room.

Clinical presentation is typical in two forms:

The “hip dislocator,” characterized by the patient asserting the ability to dislocate the hip without a correlating pain elicitation. This action is typically reproducible by the patient on bilateral weight bearing while tilting and rotating the pelvis with lateral displacement of the affected side.

This pseudosubluxation/pseudodislocation gives the visual appearance of the hip displacing, but radiographs uniformly demonstrate that the hip remains concentrically reduced.

“True” external snapping hip is characterized by snapping phenomenon at the greater trochanteric region with hip flexion and extension.

The patient nearly always relates a snapping or subluxation-type sensation. The symptoms are located laterally, and patients typically can illustrate this while standing.

As with the iliopsoas, this often is a dynamic process, better demonstrated by the patient than produced by passive examination. It may be detected with the patient lying on the side and then passively flexing and extending the hip.

The snap can be palpated over the greater trochanter, and its origin is confirmed by applying pressure, which can block the snap from occurring.

The Ober test evaluates for tightness of the iliotibial band, which may accompany symptomatic snapping.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The diagnosis of a both external and internal snapping hip is based primarily on history and physical examination, and investigative studies offer little aid in substantiating or discounting the diagnosis.

Nonetheless, plain radiographs remain an essential tool in the assessment of any hip problem.

Plain radiographs consist of an anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, AP hip, and lateral radiographs. Although these films are usually normal, some cases may show evidence of cam femoroacetabular impingement.

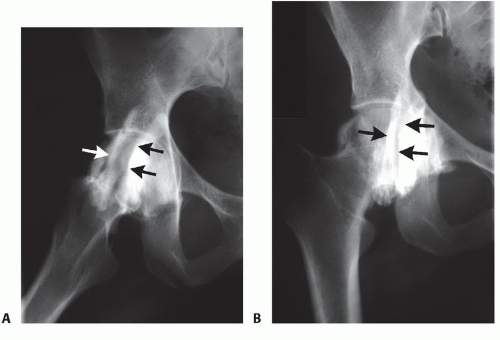

Iliopsoas bursography and fluoroscopy may dynamically document the phenomenon and be helpful to rule in, but not rule out, the diagnosis (FIG 3).

Ultrasonography of the iliopsoas is a dynamic noninvasive study that may document snapping phenomenon as well as pathologic changes of the iliopsoas tendon and its bursa.

The limiting factor with these dynamic imaging modalities is the technical proficiency of the test provider and their experience and ability to reproduce the snapping while examining hip motion.

With consideration that almost half of patients with internal snapping hip syndrome have associated intra-articular pathology,4,10,15 magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) may be performed to demonstrate any intra-articular pathology and report changes related to the iliopsoas tendon or bursa.

An image-guided intra-articular injection of lidocaine or cortisone can have significant benefit in distinguishing between extra and intra-articular hip pathology.

Table 1 Results of Surgical Treatment of Internal Snapping Hip Syndrome (Open and Endoscopic) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree