Current Concepts and Techniques in Foot and Ankle Surgery

First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Arthrodiastasis and Biologic Resurfacing with External Fixation: A Case Report

Keywords

• Hallux rigidus • Biologics • Metatarsophalangeal joint • External fixation • Arthrodiastasis

Symptomatic degenerative arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ), which encompasses a range of presentations from hallux limitus to hallux rigidus, has a variety of causes including previous osteochondral injury, biomechanical alterations, and inflammatory conditions.1 Early symptoms include pain, swelling, and stiffness in the joint with forced dorsiflexion, such as with walking, running, squatting, toe raises, or simply with passive range of motion. The patient may present with difficulty wearing shoes, especially those that require dorsiflexion of the first MTPJ, such as high heels. Advancing symptoms of hallux rigidus are noted when the patient has almost constant pain at the joint, possibly even at rest. Joint crepitus is also noted with progressing symptoms because of the formation of joint osteophytes or destruction of the articular surfaces. Enlarging osteophytosis can lead to a visible and palpable osseous mass, typically at the dorsal aspect of the joint. Depending on the severity, difficulty walking may lead to transfer metatarsalgia, as well as knee pain, hip pain, or back pain caused by patients altering their gate patterns to attempt to alleviate the strain on the first MTPJ.2 The early stages of hallux rigidus are usually amenable to conservative treatment, whereas later stages often require surgical intervention. Concomitant hallux abducto valgus deformity can compound the clinical scenario and requires careful consideration in surgical planning. Recent surgical advances have led to numerous joint-sparing options for this painful and debilitating disorder. This article presents a case illustrating an innovative surgical technique for hallux rigidus through aggressive joint debridement combined with first MTPJ biologic resurfacing and arthrodiastasis.

Case report

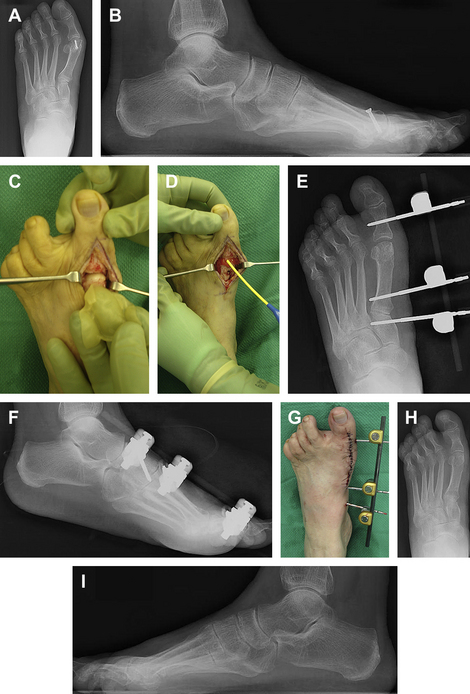

Under general anesthesia and pneumatic thigh tourniquet, a linear incision was created at the dorsal aspect of the first MTPJ followed by deep dissection to expose the joint. The first metatarsal head screw was located and removed. The metatarsal head and proximal phalangeal base were debrided of any remaining osteophytes and the articular cartilage at the first metatarsal head was inspected as the joint was distracted. Articular damage at the plantar distal aspect of the first metatarsal head was visualized and a 0.045 Kirschner wire was used for subchondral drilling. Next, a 5 cm by 5 cm collagen-glycosaminoglycan monolayer graft (Integra Lifesciences, Plainsboro, NJ, USA) was then carefully placed directly over the first metatarsal head extending proximally to the metatarsal neck. Any excess graft was resected appropriately and 5 mL of fibrin sealant was applied to secure the graft in place. The surgical site was then closed in layered fashion. The tourniquet was deflated and a new sterile field was set up about the foot for placement of the uniplane monolateral external fixation device (Stryker Hoffmann External Fixation System, Mahwah, NJ, USA). Under fluoroscopic guidance, three 3-mm half pins were inserted from medial to lateral direction: the first pin at the midpoint of the medial cuneiform, the second pin at the first metatarsal base 1 cm distal to the articular surface, and the third pin at the base of the proximal phalanx of the hallux. The monolateral external fixator was assembled with appropriate clamps followed by a long carbon fiber rod. Manual distraction and positioning of the first metatarsal was achieved while the external fixation device was secured by appropriate tightening. Intraoperative C-arm fluoroscopy was used to confirm maintained distraction at the first MTPJ. Once the construct was noted to be stable, dry sterile dressings followed by a well-padded posterior splint was applied to the lower extremity. The patient maintained partial weight bearing status to the left foot for 6 weeks, with biweekly clinic visits for serial radiographs and evaluation of incisions/pin sites. The external fixator was removed at approximately 6 weeks and the patient progressed to full weight bearing status with passive and active range of motion exercises to the first MTPJ. At 9 months’ follow-up, the patient was pain free and able to maintain her active lifestyle (Fig. 1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree