Meniscus Transplantation

Samuel P. Robinson

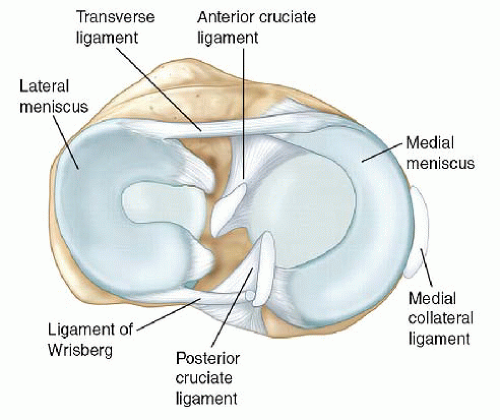

Kevin F. Bonner

The function of the meniscus in load sharing, shock absorption, joint stability, joint nutrition, and overall protection of the articular cartilage is well known (Fig. 58.1) (1, 2 and 3). As a result of our increased understanding of meniscus function, the treatment of meniscal injuries has evolved from complete resection to meniscal preservation when possible. Although meniscus preservation through repair or limited resection is always preferable, specific meniscal pathology often dictates treatment. Relatively large resections to include subtotal or total meniscectomy are not uncommon, even in young patients.

Articular contact stresses increase as a function of the amount of meniscus resected. Complete medial meniscectomy decreases contact area by 50% to 70% and doubles the joint contact stress of the medial compartment (4). Segmental meniscectomy may have a similar effect on contact area and contact stress when compared with complete meniscectomy (5). Complete lateral meniscectomy decreases contact area 40% to 50% and increases joint contact stress 200% to 300% in part due to the relative convexity of the lateral tibial condyle (4). For this reason, lateral menisectomy is considered to have a poorer prognosis than medial menisectomy with regard to the development of osteoarthritis and pain. Since the medial meniscus is also the primary secondary stabilizer to anterior tibial translation in an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-deficient knee, a large posterior horn resection in this setting often increases tibial translation and instability symptoms.

Although many postmeniscectomy patients do very well and remain relatively asymptomatic for long periods, some patients develop pain earlier in the meniscal-deficient compartment as the result of increased articular contact stresses. It also must be remembered, however, that a degenerative meniscal tear may be the earliest symptomatic clinical event that signals a complicated degenerative pathway has been initiated, which is affected by more factors than just the status of the meniscus. Nonetheless, meniscal allograft transplantation has been developed to provide symptomatic relief to select patients and potentially slow the progression of degenerative changes. Since the first meniscus transplantation in 1984 by Milachowski was reported, the technique and its indications continue to be modified and improved. Contemporary meniscus allograft transplantation after menisectomy has been shown to decrease peak stresses and improve contact mechanics, but does not restore perfect knee mechanics (6, 7). Despite these potential benefits, this remains a difficult patient population to treat. Physicians must carefully evaluate potential meniscus transplant patients and help them maintain realistic outcome expectations.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

History

Potential transplant patients are typically less than 50 years of age with an absent or nonfunctional meniscus who are symptomatic from their meniscal insufficiency. A detailed history regarding a patient’s specific symptoms, prior injuries, and subsequent surgery should be obtained. Recent arthroscopy pictures can be very helpful in determining the degree of meniscal resection and condition of the articular cartilage. Symptomatic postmenisectomy patients typically present with joint line tenderness, swelling, and activity-related pain. Symptoms may sometimes be subtle and can be associated with barometric pressure changes.

Patients with combined ACL instability and a deficient medial meniscus may complain soley of instability or combined instability and medial-sided pain. They may have a history of an ACL injury treated nonoperatively or may have recurrent instability following ACL reconstruction in the setting of a deficient medial meniscus.

Physical Examination

Physical examination should focus on location of the pain, alignment, gait, ligament stability, range of motion, muscle strength, and ruling out alternative pathology as the primary source of pain. Joint line tenderness is critical in determining the location and cause of the symptoms while ruling out other causes of pain. The pain or tenderness from meniscal deficiency is often dull and diffuse along the involved compartment. Sharp pain on McMurray test

may indicate recurrent meniscal injury or chondral lesion. Be sure to assess the knee for alternate causes of symptoms such as pes tendonitis. Evaluating a patient’s overall alignment and gait is important in determining if a corrective osteotomy needs to performed initially or potentially in combination with other procedures. Ligamentous stability should be assessed to determine the integrity and function of both the native ligaments and the prior reconstructions. Before considering a patient for meniscal transplant, the patient should have full symmetric range of motion and adequate muscle strength.

may indicate recurrent meniscal injury or chondral lesion. Be sure to assess the knee for alternate causes of symptoms such as pes tendonitis. Evaluating a patient’s overall alignment and gait is important in determining if a corrective osteotomy needs to performed initially or potentially in combination with other procedures. Ligamentous stability should be assessed to determine the integrity and function of both the native ligaments and the prior reconstructions. Before considering a patient for meniscal transplant, the patient should have full symmetric range of motion and adequate muscle strength.

Imaging

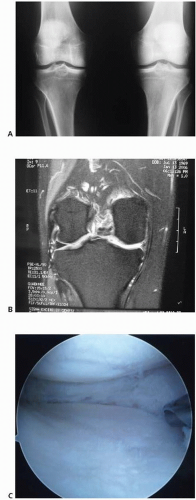

Imaging starts with plain radiographs that include weight-bearing anteroposterior full extension views of both knees, weight-bearing posteroanterior views in 45° of flexion (Rosenberg view), Merchant view, and a nonweight-bearing flexion lateral view (Fig. 58.2). These films are helpful to assess the degree of degenerative changes and subtle joint space narrowing. If malalignment is suspected clinically, long-leg alignment films are indicated to provide an objective evaluation. MRI is often helpful to assess the integrety of the menisci, articular cartilage, and subchondral bone (Fig. 58.2). Bone scan may reveal increased activity in the involved compartment, but the sensitivity of bone scan in this setting unknown.

If the last arthroscopy occurred over 6 months to 1 year before evaluation, diagnostic arthroscopy is useful to evaluate the meniscus and articular cartilage before ordering meniscal allograft tissue (Fig. 58.2). Arthroscopy in this setting will accurately define extent of prior meniscectomy and the degree of arthrosis in cases where previous arthroscopic images are unavailable or unclear. When evaluating the knee for a possible meniscal transplant, the integrity of the articular cartilage is critical. Patients with less than Outerbridge grade 3 articular cartilage changes are optimal candidates for a meniscus transplant although small areas of grade 3 can sometimes

be accepted. In the setting of a focal grade 4 lesion, this focal area may be addressed with a concurrent cartilage resurfacing procedure.

be accepted. In the setting of a focal grade 4 lesion, this focal area may be addressed with a concurrent cartilage resurfacing procedure.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis that should be considered includes recurrent meniscal tear, chondral or osteochondral lesion, advanced bipolar degenerative chondrosis, synovitis, pain emanating from the patellofemoral compartment, extra-articular knee sources (pes tendonitis/bursitis, neuroma), and hip or spine pathology. Any of these conditions may be the primary cause of symptoms rather than the proposed meniscal deficiency. However, in our experience, a small meniscal re-tear in the setting of a prior substantial meniscectomy rarely causes the patients primary symptoms. Although it may be difficult, a good examination combined with careful assessment of the studies can typically delineate who would be likely to benefit from a meniscus transplant. Injections can be helpful to differentiate intra-articular from extra-articular sources of pain. Certainly one of the most challenging aspects of meniscus transplant surgery is determining when moderate chondrosis has advanced to the point where a meniscal transplant is unlikely to yield a good clinical outcome. Although a chondral or osteochondral lesion may be the primary cause of pain in a meniscal-deficient compartment, meniscal deficiency may need to be addressed concurrently (i.e., chondroprotection of meniscus transplant).

TREATMENT

Nonoperative Treatment

Patients typically undergo a trial of conservative management. This may include activity modification to include nonimpact activities and exercises, appropriate pharmacologic therapy (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications [NSAID], etc.), injection therapy, and unloader braces. These treatment options may also be helpful for diagnostic purposes while trying to work through the differential diagnosis. A possible exception to initial nonsurgical management may be in the setting of medial meniscal deficiency combined with chronic ACL deficiency or a failed prior ACL reconstruction. A concomitant reconstruction of the ACL with meniscal allograft replacement may improve joint stability, ACL graft survival, and eventual clinical outcome (8).

Surgical Indications

Meniscal allograft transplantation is an option in the carefully selected patient with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. The procedure is typically indicated in patients less than 50 years of age with an absent or nonfunctional meniscus with symptoms of moderate-to-severe pain due to meniscal insufficiency before the development of advanced chondrosis. Younger individuals (often in their teens and twenties) presenting with joint space narrowing following meniscectomy associated with more mild pain may be considered a relative indication. Contraindications to surgery include age above 50 years (relative, not absolute), skeletal immaturity, immunodeficiency, inflammatory arthritis, prior deep knee infection, osteophytes indicating bony architectural changes, marked obesity, generalized Outerbridge grade 3 to 4 articular changes (focal chondral defects may be addressed concurrently), knee instability (unless concurrently corrected), or marked malalignment (unless concurrently corrected). A point of interest is that some authors have had success with combined medial meniscus transplant, cartilage repair, and osteotomy in select patients with unicompartment arthritis under the age of 50 (9).

Patient selection is a critical factor in achieving a successful clinical result. Meniscal transplantation improves the contact forces across the joint, which may potentially limit or slow the progression of osteoarthritic changes. Certainly a patient that has already developed severe degenerative changes will not benefit from the chondroprotective effects of a meniscal transplant. Long-term data is not currently available to justify the procedure as a prophylatic treatment in young asymptomatic patients with significant meniscal deficiency. Until further data is available to help elucidate which asymptomatic meniscectomy patients would benefit in the long term from a transplant, there is currently a subset of patients who will present within a “window of opportunity” between the onset of symptoms and the development of prohibitive degenerative arthritic changes.

An evolving indication involves patients with combined medial meniscal insufficiency and chronic ACL instability or prior ACL reconstruction failure. Patients with increased anterior translation due to loss of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and increased laxity of the other secondary restraints may potentially have improved outcomes from the ACL reconstruction when combined with a medial meniscus transplant (8). Our experience has also shown that we are able to more reliably restore stability to a chronically ACL/medial meniscus-deficient knee in either a primary or a revision setting with the combined procedure.

Preoperative Planning

Although size matching of meniscal allografts to recipient knees is thought to be critical, the tolerance of size mismatch is unknown. Authors generally recommend that meniscal transplant allografts be within 5% of the patients’ native meniscal size. Various sizing methods have been proposed, but measurements based on plain radiographs utilizing magnification markers and MRI are most commonly used clinically. On anteroposterior radiographs, the meniscal width is calculated based on the width of the compartment from the peak of the medial or lateral eminence to the boarder of the tibial plateau. The lateral radiograph is used to determine the meniscal length based on the length of the tibial plateau. After correction for magnification, the values are multiplied by 0.8 for the medial

meniscus and 0.7 for the lateral meniscus. This technique, described by Pollard (10), has been shown to successfully match the meniscus in at least 95% of cases (11).

meniscus and 0.7 for the lateral meniscus. This technique, described by Pollard (10), has been shown to successfully match the meniscus in at least 95% of cases (11).

Meniscal allografts are procured under strict aseptic conditions within 12 hours of cold ischemic time in accordance with standards established by the American Association of Tissue Banks for donor suitability and testing. Meniscal allografts have been available as fresh, freeze dried, cryopreserved, or fresh frozen although cryopreserved and fresh frozen are the most common. Fresh allografts are logistically difficult because they must be used within 7 to 14 days of harvest, but still maintain cell viability. Freeze-dried allograft preparation not only alters the biomechanical properties of the tissue, but this processing (lyophilization) has been implicated in meniscal graft shrinkage. Thus, these grafts are no longer used clinically. The cryopreservation preparation process does not affect the structural and tensile properties of the meniscus, but cell viability in the meniscus is only 10% to 40% (11). Although shown to work well and safely, cryopreserved grafts have not proved to be superior to fresh frozen in clinical trials. Fresh-frozen allografts, which do not maintain cell viability, are easier to manage clinically and are the most commonly utilized grafts at this time. Unlike osteochondral allografts, maintenance of cell viability is not believed to have clinical significance related to outcomes. Meniscal allografts become repopulated with recipient cells within 4 weeks of transplantation (12, 13).

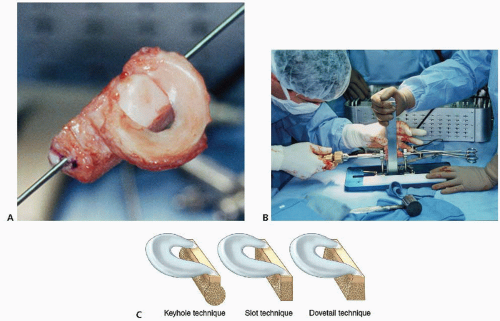

FIGURE 58.3. Lateral meniscal allograft preparation. A: Lateral meniscal allograft before preparation. B: Allograft prepa ration station—keyhole (Arthrex, Naples, FL). C: Illustration of meniscal allograft bone block preparation techniques (keyhole, slot, and dovetail). D: Intraoperative preparation of meniscal bone block (dovetail). E: Lateral meniscal allograft just before transplantation (keyhole).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|