CHAPTER 81 Medical Rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will provide the reader with a strategy for treating radicular pain and radiculopathy caused by lumbar disc herniations, stenosis, synovial cysts, and spondylolisthesis. These strategies rely on identifying the cause of nerve root irritation and tailoring the treatment algorithms based on the specific causes. The methods are based on the evidence-based literature and our groups’ collective experience. Because there is little or no evidence that commonly used treatments for radicular pain are either effective or not effective, our approach emphasizes the history and physical examination rather than imaging and electrodiagnostic studies. We will argue that the ultimate patient outcome is best predicted by the clinical presentation and early response to treatment.

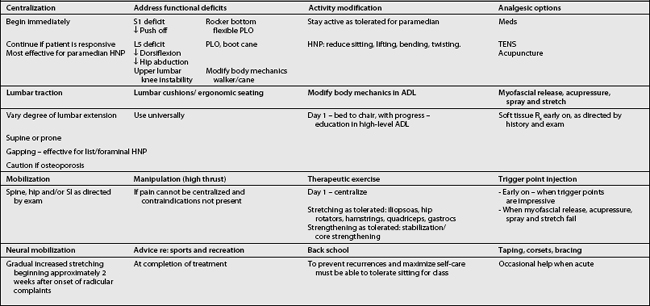

The art of treating a patient with lumbar radiculopathy involves considering many factors before deciding on or changing a course of action (Table 81.1).

THE MANAGEMENT OF LUMBAR RADICULOPATHY SECONDARY TO A PARAMEDIAN HERNIATED NUCLEUS PULPOSUS

Natural history

In a review article, Benoist reported that approximately 60% of patients with a symptomatic herniated disc will report a marked decrease in back and leg pain during the first 2 months, while 20–30% will still complain of back and/or leg pain at 1 year.1

Most studies indicate that most patients with a paramedian HNP can be satisfactorily treated with conservative measures.2–6

Komori et al. report: ‘Several well-designed studies of patients with HNP have revealed the satisfactory results of conservative treatment, although some authors have reported that about 20% of all patients had to be treated surgically during follow-up because of prolonged or aggravated leg pain.’7

Saal and Saal performed a retrospective cohort study on the success of nonoperative treatment of herniated lumbar discs with radicular pain and radiculopathy without associated spinal stenosis. All patients had a chief complaint of leg pain, positive straight leg raising of less than 60 degrees, herniated discs on computed tomography (CT) scan, and a positive electromyogram (EMG). The average follow-up time was 31.1 months. The patients underwent aggressive physical rehabilitation, including back school and stabilization training. Ninety percent reported a good or excellent outcome, and 92% returned to work after an average sick leave of 15.2 weeks.3–5,8

The patient’s history and examination not only are critical in making a diagnosis, but also allow us to forecast the likelihood of a patient’s responding to therapy alone as opposed to requiring epidural steroid injections or surgery.

Early indications for surgery

Review of the surgical literature reveals an interesting paradox. The results from surgical studies suggest that patients who do require surgery face a greater likelihood of successful outcome if they are operated on relatively soon after the onset of radicular pain. One study reported a worse overall prognosis for patients whose surgery takes place 12 months or more after the initial onset of radicular symptoms.9 Only with a clear understanding of both the natural history and effective conservative interventions for paramedian disc herniations can informed decisions be made regarding surgical consultation.

There are several studies that help predict which patients will respond best to nonoperative care. Patients who present with negative crossed straight leg raising, and the ability to extend the lumbar spine without associated radicular pain, usually respond well to conservative management.10 Patients with normal or very mild neurological deficits also have a better chance of responding to nonoperative care. We also feel that outcome is better when the onset of discogenic radicular symptoms was acute rather than insidious.

There are numerous reports of significant shrinkage, or even disappearance, of extruded herniations that usually occurs over a 3–6-month period.1,11–14 Subligamentous disc herniations, however, are often more stubborn and resolve more slowly than extruded herniations.

Activity modification

In a review of ten trials of bed rest and eight trials of advice to stay active, Waddell et al. reported consistent findings showing that bed rest is not an effective treatment for acute low back pain, and in fact may delay recovery.15 Although these patients were not carefully separated into those with axial back pain as opposed to those with radicular pain, the authors concluded that patients should be advised to remain active.

In a trial comparing 2 days of bed rest with 7 days of bed rest for patients with mechanical low back pain without neurological deficits, Deyo et al. reached a similar conclusion: the group with the shorter period of bed rest missed fewer days of work.16 No other difference was noted between the two groups in terms of their functional, physiological, or perceived outcomes.

In fact, there is no evidence that bed rest hastens recovery or improves outcome in patients with radicular pain and radiculopathy. On the contrary, numerous studies demonstrate the deterioration of many physiological systems as a result of bed rest. Abnormalities that develop include, but are not limited to, decreased cardiac output, atelectasis, orthostatic hypotension, decreased aerobic capacity, diffuse muscular atrophy, constipation, renal lithiasis, osteopenia, and depression.

On the other hand, Wiesel et al. conducted a study on military recruits with nonradiating back pain and found that those who were on brief periods of bed rest had a faster return to full duty than those who remained ambulatory.17

Despite numerous studies indicating that continued activity is preferable to bed rest, many patients have too much pain to get out of bed and will require a short period of bed rest until the severe pain lessens. Pain can often be reduced by the following: lying supine with hips and knees both in significant flexion, supported by pillows underneath the calves; lying on either side in a fetal position with the pillow between the knees; and short periods of lying prone with a pillow under the mid-abdomen. In addition, patients are advised to use firmer mattresses, with a soft, thin surface layer.18

Clinical use of medications

There is no evidence that any oral medication will change the course of lumbar radiculopathy due to a herniated disc. On the other hand, medication can help control symptoms. Patients are, however, warned to avoid activities that they know would be painful or inadvisable when not taking their medications because such activity could ultimately exacerbate rather than alleviate their symptoms (Table 81.2).

Table 81.2 Medications for lumbar radiculopathy – summary

| Non-narcotic analgesics | NSAIDs | Anticonvulsants |

|---|---|---|

| Analgesic effect only | Analgesic effect primarily | For pain with neuropathic quality, ???, burning |

| Acetaminophen – max 4 g per day | Disease altering for: synovial cyst, Facet syndrome | Most common: gabapentin, titrate up to 1800 mg per day for most, max. 3600 mg per day |

| Tamadol – max 100 g every 6 h | Selective COX-2 inhibitors, meloxicam | |

| Caution: interaction with serotonergic drugs | Salsalate – ↓GI toxicity, normal bleeding time | Caution: somnolence, dizziness, nausea |

| Caution: fluid retention, GI toxicity – add PPI, misoprostol, ↑ bleeding time, ↑ vascular events | ||

| Narcotic analgesics | Oral corticosteroids | Antidepressants |

| Analgesic effect only | Theoretically decrease root inflammation | For pain with neuropathic quality |

| Short acting | Not proven to alter course | Tricyclics – most common is amitriptyline, variable sedation, variable anticholinergic |

| Long acting – for hours, for chronic pain | Caution: AVN, multiple side effects | |

| Caution: sedation – add provigil, constipation – add laxatives, nausea, pruritus, addictive potential | SSRIs – not well studied | |

| Effexor, Paxil, duloxetine – theoretical benefit of increasing both central serotonin and neuroepinephrine | ||

| Muscle relaxants | Anti-TNF | Topical agents |

| Variably sedating | Experimental | For pain with neuropathic quality |

| Role when diffuse muscular tenderness | Anti-inflammatory – disease modifying | Lidocaine patch, capsaicin |

| Some with anticholinergic effect | ||

| Some with addictive potential |

Nonnarcotic analgesics

Tramadol (Ultram) is a weak opioid agonist with analgesic properties equal to acetaminophen/codeine combination preparations that is well tolerated by most, including the elderly. Tramadol is often prescribed as 50 mg to a maximum of 100 mg every 6 hours. It is also available in a combination tablet, which includes 37.5 mg of tramadol and 325 mg of acetaminophen (Ultracet). Tramadol has the advantage of causing less sleepiness and constipation than narcotics, with a similar analgesic benefit to mild narcotics. Uncommon side effects include sleepiness, dizziness, and nausea. Tramadol may decrease the seizure threshold in patients with epilepsy.19

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

No studies show that nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) improve either the objective signs or the long-term outcome in patients with lumbar radiculopathy. There is, however, some evidence that NSAIDs are effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute low back pain, but no specific type appears to be more effective than the others.20

There is evidence that antiinflammatories can reduce inflammatory mediators in animal studies.21 A comparison of indomethacin with placebo did not demonstrate a difference in objective neurological signs or subjective reports of pain relief.22 One study revealed a symptomatic improvement with meloxicam in acute sciatica when compared with placebo and diclofenac in a double-blinded trial.23

The first concern about the cardiovascular safety of rofecoxib emerged with the VIGOR study, reported in 2000. It involved a fivefold increase in myocardial infarction and a twofold increase in stroke, or cardiovascular death among 8076 rheumatoid arthritis patients treated for a median of 9 months with rofecoxib compared with naproxen.24–27 Further questions about the cardiovascular safety of rofecoxib were raised in 2001 by an overview of the clinical trial data.28 These data prompted the FDA to initiate a label change in 2002, highlighting the potential cardiovascular risks of rofecoxib. Despite more recent observational studies also suggesting an increased early (within the first 30 days of treatment) and late (beyond 30 days) risk of acute myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death with rofecoxib,29,30 conclusive evidence of increased cardiovascular risk from adequately powered randomized trials was lacking.31

The decision by Merck to withdraw rofecoxib worldwide was prompted by an unexpected source. APPROVe (Adenomatous Polyp Prevention On Vioxx) was a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of 2600 patients designed to examine the effects of treatment with rofecoxib on the recurrence of neoplastic polyps of the large bowel in patients with a history of colorectal adenoma.27 An interim analysis of this trial demonstrated an almost twofold increase in cardiovascular events in patients treated with rofecoxib (25 mg daily) compared with placebo. When these data are extrapolated to the Australian population, the increased risk of 16 events per 1000 patients treated for up to 3 years equates to a potential excess of several thousand cardiovascular events caused by rofecoxib. This may represent an underestimate of the number of events caused by rofecoxib, because patients with inflammatory arthritis are likely to be at higher baseline risk of cardiovascular events than the ‘low-risk’ population included in APPROVe.27

Muscle relaxants

Some studies support a weak benefit of muscle relaxants over placebo for the treatment of axial back and neck pain,32–35 but we are not aware of any trials on the use of muscle relaxants for lumbar radiculopathy.

Antidepressants

The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of radicular pain is largely unsupported. In studies comparing tricyclic antidepressants with SSRIs for chronic pain syndromes, tricyclics were found to be more effective in every case.36

Duloxetine (Cymbalta), a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI), is available in doses of between 20 mg and 120 mg per day, administered either once or twice daily. Efficacy has been demonstrated in diabetic peripheral neuropathy in two randomized, double-blind, 12-week, placebo-controlled studies in which patients were followed for at least 6 months.37,38 Improvements were seen as early as 1 week after initiating the drug. Doses above 60 mg per day did not offer greater improvement. The drug is contraindicated in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma, as well as in patients with end-stage renal disease or hepatic insufficiency. Most commonly observed adverse effects include nausea, dry mouth, constipation, fatigue, decreased appetite, somnolence, and increased sweating. The overall discontinuation rate due to adverse events was 14%, compared with 7% for placebo.

Anticonvulsants

The antiepileptic drug lamotrigine (Lamictal) has recently been studied in the management of intractable sciatica.39 The study demonstrated improvements in lumbar range of motion, straight leg raising, and a short form of the McGill pain questionnaire.

Oral corticosteroids

Although short courses of corticosteroids are often prescribed for radicular pain, there are no double-blind, placebo-controlled trials supporting or not supporting the use of corticosteroids for the treatment of radicular pain caused by a herniated disc or spinal stenosis.40 Because of the risk of avascular necrosis of joints with the intake of 60 mg doses of dexamethasone,41 we only occasionally treat radicular pain with oral corticosteroids.

Antitumor necrosis factor medications

Several recent studies show that tumor necrosis factor TNF-α may be a significant pain mediator in radicular pain.42,43 According to Murata et al.,43 TNF-α is produced and released from chondrocyte-like cells of the nucleus pulposus and acts to reduce nerve conduction velocity, induce intraneural edema and intravascular coagulation, reduce blood flow, and cause myelin splitting. Murata treated rats with intraperitoneal infliximab (Remicade), a selective inhibitor of TNF-α and showed that injected rats produced a significant reduction in histologic changes in the dorsal root ganglion.

Korhonen et al. demonstrated the beneficial effect of a single infusion of infliximab, 3 mg per kg, for herniation-induced sciatica.44 Eight of the 10 patients treated with infliximab remained pain-free 1 year after injection, and no ill effects were reported in any of the 10 patients. Six of the 10 had achieved pain-free status at 2 weeks, seven at 4 weeks, and nine at 3 months. All had severe sciatic pain below the knee, positive straight leg raising at less than or equal to 60 degrees, and a disc herniation concordant with symptoms on MRI. By comparison, only 43% of the 62 control patients, who also had disc herniation-induced sciatica, were pain free at 12 months.

Topical agents

Lidocaine 5% patch reduces pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia without toxicity. The only side effect is an occasional local rash. Lidoderm patches have been tried in various conditions associated with neuropathic pain. Although the drug’s insert instructs that the use should be an on-and-off 12-hour schedule, there does not appear to be any physiological risk to 24-hour use of the patch. There are, however, no studies demonstrating efficacy in lumbar radiculopathy.45

Physical therapy

Superficial cold (cryotherapy)

Application of cold packs placed in wet towels or ice massage can afford temporary analgesia.46 Cold causes vasoconstriction of superficial vessels, indirectly resulting in vasodilatation of deeper vessels. Contraindications to cryotherapy include cold hypersensitivity and urticaria, Raynaud’s phenomenon, cryoglobulinemia, and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. In addition, cryotherapy should not be applied to areas of skin anesthesia or decreased circulation. Vapo-coolant spray and stretching (spray and stretch) can also be used for the management of myofascial pain. This is often used in combination with trigger point injections as described by Travell and Simons.47

Heat (thermotherapy)

Heat can be used as a temporary analgesic,48 and can be administered by hydrocollator packs, heating pads, hydrotherapy, or thin wraps that can be placed on the skin for a prolonged application. In fact, heat wraps have been demonstrated to be more effective than ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute low back pain,49 and are helpful for relieving overnight pain.50 Diathermy and ultrasound are usually ineffective in reducing radicular pain.

Electrotherapy

Various forms of electrical stimulation, such as high-voltage pulsed galvanic stimulation or interferential electric stimulation, can be applied in the office setting, either in isolation or in conjunction with heat or cold. These modalities seem to contribute to relaxation and temporary analgesia, perhaps through decreasing spasm. Electrical stimulation should not be applied to patients with cardiac pacemakers or defibrillators, or to anesthetic areas or incompletely healed wounds.51

TENS uses a small pulse generator clipped to the skin connected to one to four variously placed transcutaneous electrodes. The pulse frequency, amplitude, and wave form are adjusted to achieve maximal effect. TENS can provide analgesia,52 but there are no specific trials evaluating the efficacy for treating lumbar radiculopathy. In general, TENS has an occasional role and may be most useful in decreasing night pain.

Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) uses needle probes similar to those used in acupuncture to deliver electrical pulses to peripheral sensory nerves at dermatomal levels.53 In a trial comparing PENS, sham PENS, TENS, and exercise, both PENS and TENS were effective in reducing sciatic pain. Although PENS was more effective, because it is a tedious in-office procedure, supported by only a few studies, and does not help structurally, PENS has not been used in our management of radicular pain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree