CHAPTER 76 Medical Causes of Low Back Pain

INTRODUCTION

Pain arising in the lumbar region of the spine can be due to many causes and, in as many as 80% of cases, these causes cannot be established with certainty.1 Many terms have been proposed as a label for the condition affecting this vast majority of patients, for example primary, idiopathic, common, or mechanical low back pain, strain, injury, and trouble. Here, we use what is the most common, and probably the correct, definition: low back pain (LBP).

LBP is currently recognized by most authors as a bio-psycho-social syndrome2 in which pain constitutes the final common pathway with many possible causes. The course of this complex process begins with the acute onset of pain; in the sub-acute stage, and the interaction of psychological and social factors create the final, individual clinical picture, of chronic pain.1,2 If one accepts this mechanism it becomes clear that we cannot consider only the biological (anatomical) aspects of LBP. Restricting one’s view of its medical causes, at worst to the single painful tissue, and at best to impaired functional mechanisms (a somewhat risky approach given that nobody can categorically state which tissues are most commonly involved in LBP), one will see that the hypotheses are as numerous as the scientists who have advanced them.

From an academic point of view, one can divide the medical causes of LBP into three categories: biological, psychological, and social. This approach is entirely consistent with the aforementioned bio-psycho-social model of LBP,2 and with the only currently meaningful classification of the condition, which classifies LBP on the basis of the temporal course of the syndrome: acute (up to 4 weeks of pain), subacute (5 to 12 weeks), and chronic (more than 12 weeks).3,4 This classification differentiates between primary and secondary causes of back pain. The value of this classification is mainly prognostic: the acute phase is benign (spontaneously resolving), whereas resolution of the chronic phase is rare (less than 5–10% of cases).1,5 But this classification could also have etiological significance: whereas the acute phase could be regarded as almost completely biological, and the subacute period to correspond to the gradual evolution toward the complete syndrome, the chronic phase is believed by many authors to be purely psychosocial.1,3 Conversely, there is compelling evidence suggesting that chronic LBP is the expression of a full picture of biological dysfunction.3,6

LOW BACK PAIN

Biological causes of acute low back pain

Previous studies have focused on the development of the pain sensation and on the tissues in which pain may originate.7 Many researchers have proposed a single tissue as the main source of LBP even though, in this regard, consensus appears to be lacking.

Pain mechanisms

Acute LBP is a nociceptive pain.7 It is initiated by the activation of free nerve endings (pain receptors), which are present in most body tissues (skin, muscles, fasciae, joints, blood vessels). Nerves and nerve stimulation by various chemical substances are an important area of research. Another interesting new field of research concerns the central pain-mediating pathways and the way pain sensation is controlled at different stages.8

Nociception

Free nerve endings of C fibers can be found in vertebral body endplates, in the disc anulus, generally in the outer posterior fibers, but not in the inner disc; they are also present in muscles, tendons, capsules, and ligaments (with the exception of the yellow ligaments).7 Nociceptors usually have a high noxious threshold: they do not respond to light pressure, stretching, muscle contractions or joint motion within physiological range, but in certain environmental conditions (inflammation, vibration, etc.) they are sensitized, and their stimulus threshold is reduced. Tissue changes induced by inflammation cause the release of endogenous substances (bradykinin, prostaglandins, histamine, cytokines, and nerve growth factors) most of which sensitize nociceptors. In this way, chronic inflammation and fibrosis are related to LBP. Nociceptor activation in tissue inflammation leads to enhanced activity (dysesthesia) in other receptors, and to a reduced mechanical threshold: consequently, a greater number of receptors are stimulated by lighter mechanical stimuli, such as physiological joint movements.

Hypoxia also causes nociceptor sensitization;7 in LBP this phenomenon has been shown during muscular spasm.9 There also exists a withdrawal reflex in acute LBP in which noxious peripheral stimulation, at the joint or ligament level, could activate a motor nerve and its associated muscle. Thus, spasm activates other nociceptors and a cycle is established that results in persistent pain.10 The sympathetic pathway can also be stimulated, causing ischemic or causalgic pain.11

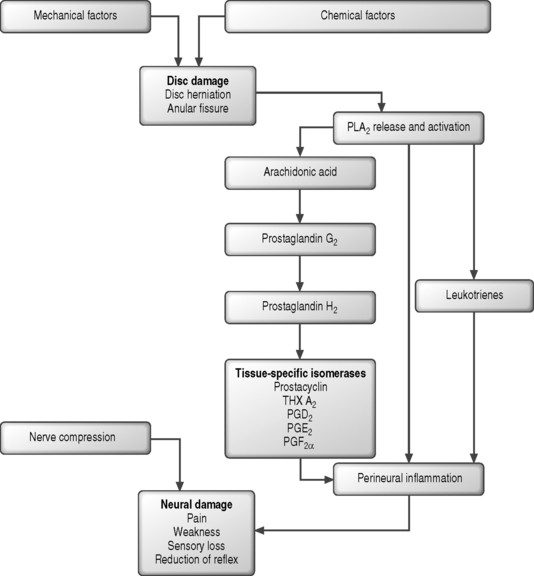

Biochemistry

Recent research has shown that cytokines such as matrix metalloproteinase, phospholipase A2, nitric oxide, and tumor necrosis factor-α may contribute to the development of LBP,12 and that mechanical and metabolic factors interact closely to produce nerve damage and pain.13,14 A current hypothesis is that leakage of these agents may produce nociceptor excitation, direct neural injury, nerve inflammation, or increased sensitivity to other pain-producing substances (such as bradykinin), and lead to nerve root pain. PLA2 and other substances, e.g. substance P, VIP (vasoactive peptide) and calcitonin gene-related peptide,15 are sources of pain. They are released following stimulation, mainly from the dorsal ganglion, where substance P plays an important role in modulating central pain and stimulating the cellular elements of inflammation (mastocytes, histamine, and leukotriene release). The stimulus is often mechanical, such as whole-body vibration.16 The damage produced by mechanical causes and enzymatic processes in outer annular fibers allows PLA2 to enter the epidural space. Damage of the disc and then the motion segment enhances susceptibility to vibrations and extreme loading conditions, establishing a cycle of dorsal ganglion stimulation and neurotransmitter release.

Central pathways and gates

The idea that there is cross-interference between skin and pain sensations, due to their convergence on the same medullary neuron, has long been an accepted theory (the gate control theory).17 In recent years, new control mechanisms (gates) have been proposed, mainly involving descending pathways that originate from the emotional centers in the brain and converge on the same neurons.18 Their major contribution seems to be that of opening the gate and keeping it open or in some cases, the reverse. These findings could provide explanations for the cross-interference between pain sensation and emotions and for other psychosocial aspects of pain. Moreover, the recent finding of reduced limb reaction times in chronic LBP patients has induced some authors to suggest the existence of a central nervous system impairment in chronic pain.19

Painful tissues

Discs

In the past, discs were not believed to be innervated. Now, however, it has been demonstrated that there are plenty of nerve endings in tissues surrounding the disc: the posterior longitudinal ligament, the outer third of the posterior anulus, the vertebral body, the dura, and the peridural venous and arterial plexuses.20 Innervation is by the sinuvertebral nerve and by the ventral and gray ramus. There are no intradiscal vascular structures, with the closest residing in the nearby endplates; therefore, tissue healing following damage is slow and very limited. In damaged discs, disc chondrocyte activation is directed at type II and type I collagen, which are typical of the outer fibers of the anulus, and the elastin, which is the interface between the disc and vertebral body. The causes of these changes, which remain to be completely defined, may be genetic, mechanical or biochemical. What is certain is that they can trigger a cascade of biochemical processes influencing damage and injuries together with the mechanical forces.21 In spite of this knowledge, the pathogenesis of discogenic pain remains uncertain. Two proposed mechanisms of disc injury suggest the process begins in the outer anulus following an exaggerated motion mainly in flexion and rotation or in the inner fibers and subsequently extends to the peripheral ones. In a study comparing inner annular lesions and disc degeneration, the inner annular lesions were found to be related to LBP.22

Another area of research has been disc oxygenation, nutrition, and catabolic wash out, mainly due to the vessels in the vertebral body and to osmotic mechanisms.23 Movement increases these metabolic changes, as do circadian variations of posture (upright and supine), and even certain exercises. Impairment of these mechanisms has been proposed as a possible source of pain.24

Nerve roots

Pressure on nerve roots can be due to spondylotic encroachments, disc herniations, foraminal narrowing, venous dilatation, and thickening of ligaments. Nerve roots exit at different angles: lower roots are more oblique and have a longer path, and thus different exposure to mechanical stress. Continuous stable pressure on a normal nerve usually causes only a brief discharge of impulses, but if the nerve has been injured by demyelinization or inflammation, pressure causes a prolonged discharge.25,26

Experimental studies have revealed the presence of many different bioactive substances in herniated disc tissue. Cytokines, in particular, exert a harmful effect on the nerve root27 and play an important role in LBP. This also provides an explanation for radicular pain in the absence of mechanical nerve root compression.

Dorsal ganglia

The dorsal ganglia, which are located in the middle zone of the intervertebral foramina, contain many types of sensory cell bodies and modulate the transmission of pain. They are capable of producing significant quantities of neuropeptides (substance P, enkephalin, and other neuropeptides) following nociceptive and mechanical stimulation.21 Substance P primarily modulates central pain28 and this explains the pain latency following herniated disc pressure. The dorsal ganglion can be a primary source of pain, due to local mechanical pressure from the disc, osteophytosis, stenosis, local neuropeptide production changes due to inflammation or chemical lesion, or ischemic damage produced by root pressure. The nerve root ganglion has an extensive venous plexus which, if obstructed, results in venous hypertension and endoneural edema, which in turn leads to hypoxia, ischemia, and pain.

Facet joints

In an animal model, posterior joints contain high-threshold mechanosensitive fibers, which function as nociceptors, and low-threshold fibers, which modulate proprioceptive feedback.29 These fibers are also found in joint capsules near the ligamentum flavum and in muscles and tendons. Facet joints have often been suggested as an etiology of LBP following the demonstration of local and distal pain following local injection of 3–8 mL of hypertonic solution.30 However, these results were subsequently refuted by the demonstration that facet joints could hold only 2 mL of solution and therefore the studies were effectively investigating periarticular tissue stimulation, due to the solution leaving the joint.31,32 Although for some authors clinical correlation of facet pathology as a primary cause of LBP remains controversial,1 many studies demonstrate a high prevalence of facet joint pain in low back syndromes and the usefulness of specific interventions.33

Ligaments

Most of the vertebral tissues are innervated by the medial ramus of the dorsal nerve. The posterior longitudinal ligament is innervated by the sinuvertebral nerve, which is formed from the union of the ventral branch (somatic) and the gray communicant (sympathetic). A specific relationship between ligamentous injury and spinal pain conditions cannot easily be established but ligaments contribute generically to LBP. In segmental instability, pain is related to ligament disruption and the loss of support. In 1968, Murphey34 demonstrated pain related to the posterior longitudinal ligament and posterior anulus stimulation, called ‘true referred pain,’ different from sciatica secondary to nerve root stimulation. In this study, a central disc protrusion caused severe lumbar pain radiating to both lower limbs, typically increasing with anterior flexion.

Muscles

No pathognomonic changes in muscles, tendons, and ligaments are shown by NMR in LBP; nevertheless, some studies35 have shown a unilateral reduction of the muscle mass in chronic LBP, but other studies refuted these findings.36 In any case, there is presumably a difference between chronic and acute LBP. LBP quickly develops after muscular injury following direct trauma or an acute overly rapid or excessive eccentricity. Typically, such pain resolves in 1–3 weeks. Some researchers have also postulated that afferent impulses directly increase muscle tension and affect blood circulation, generating ‘ischemic-like’ pain.37 It also seems that pain from trigger points could have the same mechanism, but a more recent study reported changes of gamma fibers caused by muscular tension.38

Other hypotheses

Jayson proposed that most LBP syndromes derive from epidural venous stasis, followed by local chronic inflammation and fibrinous exudation, like a common postphlebitic syndrome of the skin. The usual clinical manifestations are pain that worsens during the night and improves during activity or during maneuvers that usually aggravate disc pain.39 Epidural venous stasis may also directly provoke sciatica by perivenous nervous plexus stimulation.40

Psychosocial causes of chronic low back pain

Most patients with acute LBP improve naturally, regardless of what specific intervention is instituted,5,41 and 85–90% of these patients derive benefit from analgesics, good advice, and reassurance. Research into the causes of LBP in such cases will presumably lead to the development of new drugs and new ways of accelerating the recovery rate.

The remaining 10–15% of patients are at risk of developing chronic LBP, defined as disabling LBP that lasts longer than 3 months and does not resolve spontaneously.1,5 Symptoms and unsatisfactory pain treatments themselves become a source of disability and have a major impact upon patients’ lives, families, and jobs. These LBP sufferers generate the vast majority (90%) of the social costs related to LBP.1,5,42 In these patients, examining the causes of LBP means considering the factors that contribute to the persistence of pain over time, and preclude full recovery, i.e. the so-called risk factors.

Risk factors for chronic low back pain

Individual risk factors

The strongest associations are previous LBP and age,43 while weaker associations were found with gender,44 weight,45 and smoking.46 There was little evidence for an association between level of fitness47 or radiographic abnormalities and chronic LBP (Fig. 76.1).48,49

Physical and biomechanical risk factors

Physical and biomechanical risk factors50,51 have been shown to only weakly correlate with LBP. Only a few studies support the possibility that there is a causal relationship between chronic LBP and physical workload in the workplace.52,53 The most frequently reported variables include heavy lifting,54 motor vehicle driving,55 whole-body vibration,56 excessive spinal loading,57,58 and awkward postures.59

Psychosocial risk factors

Psychosocial risk factors,1,60,61 specifically job dissatisfaction, are an important predictor of chronic LBP. Their relative importance when compared to physical factors is unclear, but there is increasing empirical evidence linking LBP with psychosocial risk factors. The main psychosocial predictors are: work characteristics (job satisfaction and level of commitment), disability benefit, previous LBP treatment and patient satisfaction, and level of education. In particular, job satisfaction and social aspects were the factors found to be the most significant with respect to the development of severe LBP.

Psychosocial problems are likely more significant than biological factors in the development of persistent low back pain rather than its onset.1,2,48 Patients who say that they are in poor health, describe general symptoms, and say that they always feel ill (illness behavior) are more likely to have chronic pain, despite receiving the usual pain treatments. The symptoms they report seem to reflect a psychological condition more than a biological aspect of their original LBP. Most authors reported that, after only 1 year, the severity of initial LBP no longer shows a relationship with disability status.62,63 This underscores how psychosocial variables play an important role in pain perception and its evolution, once the chronic phase has been entered. There seems to be a significant, and predominant, psychosocial component underpinning prolonged disability secondary to LBP.

As indicated by Waddel in 1987,2,64,65 chronic LBP is a complex psycho-socio-economic phenomenon. Psychosocial factors do not only play a significant role in determining which injured workers will develop chronic LBP and any disability, but they also interact closely with physical/dysfunctional factors in determining the very onset of disability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree