Medial Displacement Osteotomy of the Calcaneus and Flexor Digitorum Longus Transfer

Michael K. Shindle

Roger A. Mann

Gregory P. Guyton

Brent K. Ogawa

Patients with a painful, flexible flatfoot due to posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) are treated with a variety of operations. One option, which does not involve arthrodesis, is medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy with a flexor digitorum longus (FDL) transfer. The osteotomy is designed to enhance the correction of the deformity and improve the longevity of a simultaneously performed FDL tendon transfer (1). The indications for operative intervention are similar to those for the FDL tendon transfer alone, but the osteotomy can be used to improve the posture of the foot in patients with a flexible deformity and increased hindfoot valgus (i.e., PTTD stage IIa and IIb deformity) (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). In stage IIb, patients generally have more deformity clinically, with more than 30% talar head uncovered on standing anteroposterior (AP)

radiographs (3). Surgical treatment for stage IIb is controversial, and some surgeons commonly use lateral column lengthening (3,7,8) while others use it rarely, if at all (4). The appropriate indications for choosing one approach over another remain controversial, and long-term follow-up data are not yet available. No factors have been identified that can clearly delineate a group of patients who would benefit from one procedure over another. Distraction arthrodesis of the calcaneocuboid joint does have some disadvantages in the early perioperative period, including the partial loss of hindfoot motion, the necessity for bone graft, a relatively high rate of nonunion and hardware prominence, and a tendency to exacerbate mild degrees of fixed forefoot varus during the correction.

radiographs (3). Surgical treatment for stage IIb is controversial, and some surgeons commonly use lateral column lengthening (3,7,8) while others use it rarely, if at all (4). The appropriate indications for choosing one approach over another remain controversial, and long-term follow-up data are not yet available. No factors have been identified that can clearly delineate a group of patients who would benefit from one procedure over another. Distraction arthrodesis of the calcaneocuboid joint does have some disadvantages in the early perioperative period, including the partial loss of hindfoot motion, the necessity for bone graft, a relatively high rate of nonunion and hardware prominence, and a tendency to exacerbate mild degrees of fixed forefoot varus during the correction.

The FDL transfer alone can have a satisfactory clinical result, but it rarely results in a significant change in the posture of the longitudinal arch (9, 10 and 11). There have also been concerns about the longevity of the FDL transfer alone when the arch remains uncorrected. As an isolated procedure, the FDL transfer continues to be useful in the management of recalcitrant posterior tibial tendinosis that has not progressed to a pes planus deformity (i.e., PTTD stage I). For patients with any detectable degree of deformity, adding a calcaneal osteotomy to the procedure confers a degree of mechanical protection to the tendon transfer while incurring little operative morbidity or additional recovery time.

The medial displacement osteotomy functions through static and dynamic mechanisms. Simplistically, a flatfoot can be viewed as a tripod in which one leg is collapsed: The hind leg of the tripod corresponds to the heel, and the two medial/lateral legs correspond to each border of the forefoot. If the hind leg of the tripod has fallen too far to the lateral side, the entire construct will sag medially. The medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy is analogous to restoring this posterior leg back into position, thereby raising the arch on the medial side. This is an old concept, first proposed in 1893 by Gleich (12) and later extended to the adolescent flatfoot in the modern literature by Koutsogiannis (13). Havenhill et al. (14) used pressure sensitive film in a cadaver model to demonstrate that a medial displacement calcaneus osteotomy also corrects the pathologic tibiotalar contact characteristics associated with an adult-acquired flatfoot. This may avert the onset of pantalar disease associated with late-stage PTTD.

A dynamic mechanism for the function of the medial displacement osteotomy has also been proposed (5,6). When the hindfoot sags into valgus, the line of pull of the Achilles tendon moves laterally, which tends to pull the calcaneus further into valgus and accentuate the deformity. The osteotomy brings the Achilles insertion back toward the midline. Although this mechanism is not responsible for the radiographic improvement in the arch, it may play a role in reducing the forces on the transferred FDL tendon.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The indication for a medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy with an FDL transfer is a patient with painful PTTD with a flexible flatfoot deformity.

The contraindications for the procedure are identical to those for the FDL tendon transfer alone (1,5,6) and include a rigid flatfoot, hindfoot arthritis, peripheral neuropathy, infection, and dysvascular foot. The foot must be flexible for the procedure to succeed. The subtalar joint must be at least able to invert 15° to 20°, and there must not be a fixed varus deformity of more than 10° to 15° of the forefoot relative to the hindfoot. Forefoot varus is a fixed torsional deformity through the midfoot that occurs with long-standing deformity; the forefoot accommodates to balance the valgus malalignment of the hindfoot to maintain the foot in a plantigrade position (15). In a fixed varus deformity, the lateral border of the foot is more plantarflexed than the medial border when the heel is manually corrected to neutral by the examiner.

Other surgical options for the treatment of the adult flatfoot exist and may be more appropriate for a given patient. Rigid deformities of the hindfoot or forefoot must be addressed with a triple arthrodesis; by taking down the transverse tarsal joint, the forefoot can be derotated relative to the position of the hindfoot. Even in flexible deformities, a subtalar arthrodesis combined with debridement of the tendon can be used to bypass the posterior tibial tendon and control the hindfoot (16, 17 and 18). Although much of the ability of the foot to accommodate to uneven ground is lost, an isolated subtalar arthrodesis is very durable and does not incur a major risk of causing symptomatic arthritis in the adjacent joints. More importantly, subtalar fusion is a very reliable procedure in the nonsmoking patient, and the length of time to maximum recovery is much shorter than that of the FDL transfer with or without calcaneal osteotomy (17). The durability and dramatically shortened rehabilitation period make subtalar fusion an attractive option for patients older than 70 years of age or who are morbidly obese.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

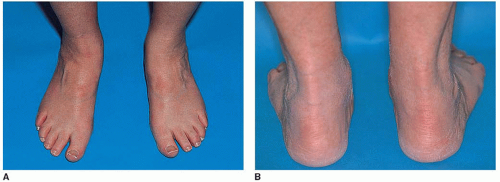

The physical examination is important for the patient who presents with a painful flatfoot. Patients often have a unilateral flatfoot (Fig. 19.1) and abnormal single heel rise test (Fig. 19.2).

The medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy with FDL transfer will fail in the presence of limited subtalar inversion or a fixed forefoot varus of more than 15°. Conversely, a patient without any significant deformity who has isolated PTTD may be well served by an FDL transfer alone.

PTTD is not the only cause of the pes planus deformity in the adult. Arthrosis of the medial tarsometatarsal joints is often accompanied by collapse of the longitudinal arch, and special attention should be paid to determine that the deformity originates at the hindfoot level rather than the midfoot. Neurologic dysfunction and peroneal spasticity should be ruled out, and the vascular status of the foot should be examined.

Obtaining a thorough history from the patient regarding the nature of the problem and the impairment of activities can help determine what type of treatment is optimal. Symptoms can be dramatically improved in some patients using an ankle-foot orthosis or a reinforced, leather ankle lacer. Other nonoperative treatments that should be considered for PTTD include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, activity modifications, and cast immobilization. Corticosteroid injection is generally not recommended.

The decision to undertake surgery should not be taken lightly. Recovery from FDL transfer is remarkably slow; our data indicate the median time to (self-reported) maximal medical improvement is 10 months.

Radiographic evaluation consists of weight-bearing radiographs of the foot, including AP, lateral, and oblique views. In cases of PTTD, the AP foot radiograph reveals increased abduction of the foot with increased exposure of the talar head (uncovered talar head) as the axes of the talus and calcaneus diverge (Fig. 19.3A). On the lateral weight-bearing foot view (Fig. 19.3B), the talonavicular joint sags and can be measured by the angle between the axis of the talus and the axis of the first metatarsal (i.e., talometatarsal angle).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Surgery consists of two separate procedures: a medial displacement osteotomy and a FDL transfer. The osteotomy is routinely done first to allow the foot to be immediately immobilized on completion of the FDL transfer. A third procedure is often performed; Achilles tendon lengthening.

Medial Displacement Calcaneal Osteotomy

The patient is placed on the operating table, with a large “bump” under the ipsilateral hip to facilitate access to the lateral side of the foot. A thigh tourniquet is used to avoid compressing the muscle belly of the FDL, which must be transferred in the second stage of the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree