Medial Ankle/Deltoid Ligament Reconstruction

Beat Hintermann

Markus Knupp

Victor Valderrabano

DEFINITION

Pronation injuries of the ankle joint complex may result in a partial or complete disruption of the superficial anterior bundles of the deltoid ligament.

Chronic medial ankle instability may cause a secondary posterior tibial dysfunction over time, as the tendon may become elongated, ruptured, or both.

Conversely, medial ankle instability may also result from a posterior tibial dysfunction with chronic overload of the deltoid ligaments and consecutive step-by-step disruption.

Medial ankle instability must be suspected if the patient complains of “giving way,” especially medially, when walking on even ground, downhill, or downstairs. Further signs can be pain at the anteromedial aspect of the ankle and sometimes pain on the lateral ankle, especially during dorsiflexion of the foot.

ANATOMY

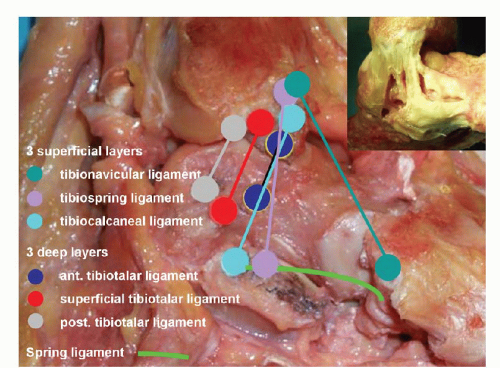

The deltoid ligament is a multibanded complex with superficial and deep components.

It may be wise to differentiate the superficial and deep portions of the deltoid complex with respect to the joints they are spanning. The superficial ligaments cross two joints (the ankle and the subtalar joints) and the deep ligaments cross one joint (only the ankle joint), although differentiation is not always absolutely clear.10

The three superficial and more anterior bands are the tibionavicular, tibiospring, and tibiocalcaneal ligaments; the three deep bands are the anterior, intermediate, and posterior tibiotalar ligaments (FIG 1).1

PATHOGENESIS

Acute injuries to the medial ankle ligaments can occur during running downstairs, landing on an uneven surface, and dancing while the body is simultaneously rotated in the opposite direction. A key feature is whether the patient has sustained a pronation (eversion) trauma—for instance, an outward rotation of the foot during simultaneous inward rotation of the tibia.

Complete deltoid ligament ruptures are sometimes seen in association with lateral malleolar fractures or in specific bimalleolar fractures.

Chronic deltoid ligament insufficiency can be seen in a number of conditions, including posterior tibial tendon disorder, traumatic and sports-related deltoid disruptions, as well as valgus talar tilting in patients with previous triple arthrodesis or total ankle arthroplasty.

NATURAL HISTORY

There is evidence that the medial ankle ligaments are more often injured than generally believed.4,5,6,8

Several structures contribute to the stabilization of the medial ankle, and in the case of injury, they are not involved in a uniform way. Medial ankle instability is thus not a single entity, and this has important consequences on the treatment strategy.

The findings of an exploratory, prospective study on 51 patients (53 ankles) has supported our belief that medial ankle instability without posterior tibial tendon dysfunction does exist as an entity.8 It is, however, not clear yet whether or to what extent such a medial ankle instability may cause a secondary posterior tibial dysfunction over time, as the tendon may become elongated, ruptured, or both.

What is clear from the literature is that a coexisting pronation deformity of the foot will lead to further deterioration over time, as the medial ankle ligaments are chronically overstretched.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The diagnosis of medial ankle instability is made on the basis of the patient’s history and the results of physical examination, including special maneuvers, and plain radiographs.

As mentioned earlier, medial instability is suspected if the patient complains of giving way, especially medially, when walking on even ground, downhill, or downstairs. Further signs can be pain at the anteromedial aspect of the ankle and sometimes pain on the lateral ankle, especially during dorsiflexion of the foot.

A history of chronic instability, manifested by recurrent injuries with pain, tenderness, and sometimes bruising over the medial and lateral ligaments, is considered to indicate combined medial and lateral instability that is thought to result in rotational instability of the talus in the ankle mortise.

Acute injuries may present with tenderness and hematoma at the medial side of the ankle.

Physical examination methods for chronic medial ankle instability should include the following:

Standing test: Inspect for malalignment, deformity, asymmetry, and swelling. Asymmetric planus and pronation deformity of the affected foot may indicate medial ankle instability: distinct, moderate, and important.

Palpation of anteromedial ankle: Pain in the medial gutter is typically provoked by palpation of the anterior border of the medial malleolus. It is the result of underlying synovitis due to chronic shifting of the talus within the ankle mortise.

Anterior drawer test is a highly sensitive test for medial ankle instability.

A complete examination of the hindfoot should also include evaluating associated injuries and ruling out other possible causes. These include, among others:

Fractures of the medial malleolus: After an acute injury, radiographic analysis must be performed routinely to exclude a fracture of the medial malleolus (eg, bony avulsion of the deltoid ligament) or fibula fracture with or without syndesmotic disruption.

Loss of posterior tibial function after partial or complete rupture: The patient cannot correct the deformity while standing or cannot create supination power to the foot.

Talonavicular coalition: The subtalar joint is not mobile so there is no varization of the heel while going into the tiptoe position.

Neurologic disorder: There is partial or complete palsy of one or more muscles due to deficient neurologic control.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Acute injury: Plain radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views, should be obtained to rule out bony avulsion fractures or associated injuries.

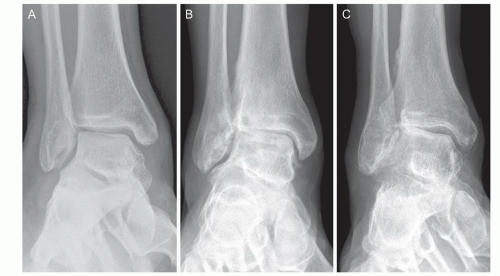

Chronic injury: Plain weight-bearing radiographs, including AP views of the foot and ankle (FIG 2), a lateral view of the foot, and a hindfoot alignment view,13 should be obtained to rule out old bony avulsion fractures, secondary deformities of the foot (eg, valgus malalignment of the heel, dislocation at the talonavicular joint), and tibiotalar alignment (eg, medial gapping of the joint due to incompetence of the deltoid ligament).

Stress radiographs may be helpful to identify incompetence of the deltoid ligament in the treatment of acute ankle fractures,14 but they are not helpful in chronic conditions.10

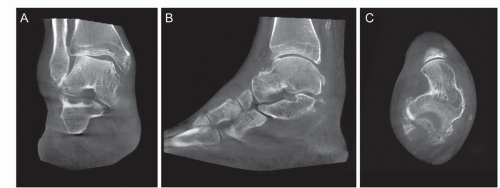

A computed tomography (CT) scan may be obtained to detect a talocalcaneal coalition or bony fragmentation that involves the articular surfaces. A weight-bearing CT may be beneficial to recognize the specific position of talus within the ankle mortise and a potential incongruency in the subtalar joint, as given by an accompanying peritalar instability (FIG 3).

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may show an injury to the deltoid ligament (FIG 4), particularly in acute conditions, and it may also reveal pathologic conditions of the posterior tibial tendon.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Bony avulsion fracture of the medial malleolus (with or without fracture of the fibula or syndesmotic disruption)

Fixed flatfoot deformity (eg, acquired flatfoot deformity in adults after posterior tibial dysfunction)

Osteochondral injury

Talocalcaneal coalition

FIG 3 • Weight-bearing CT in a patient with severe instability (same patient in FIG 2C). A. AP coronal plane. B. Sagittal plane. C. AP horizontal plane. |

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Although nonoperative management is controversial, patients with less instability, particularly those who have less of a giving way feeling and those who are less involved with high-level pronation sports activities, may be treated nonoperatively.

Nonoperative treatment consists of three components:

Medial foot arch supports

Physiotherapy for strengthening the invertor muscles

A neuromuscular rehabilitation program

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

All imaging studies are reviewed.

Plain films should be reviewed for fractures, cartilage lesions, hindfoot and midfoot malalignment, and the presence of any hardware (from previous procedures) or foreign bodies.

Associated fractures, cartilage lesions, foot malalignment, and tendon disruption should be addressed concurrently.

Examination under anesthesia should be performed to compare with the contralateral ankle.

Positioning

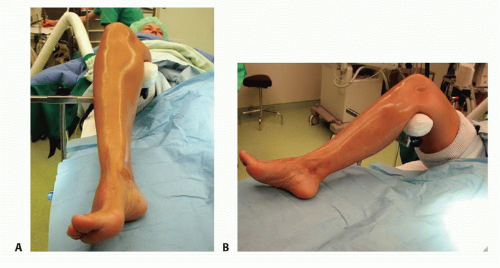

The patient is in a supine position with the feet at the edge of the table.

A commercially available knee holder is used to support the distal femur and to place the foot into a hanging position (FIG 5).

This allows the surgeon to move the foot freely while arthroscopy is done before open reconstruction.

After the arthroscopy, the knee holder is removed, leaving the foot on the table.

Approach

An anteromedial approach is used for ankle arthroscopy.5

A gently curved incision of 3 to 5 cm is made, starting 1 cm cranially of the tip of the medial malleolus and running toward the medial aspect of the navicular bone.

If there is additional instability of the lateral ankle ligaments, as found on the clinical examination and confirmed by arthroscopy, a lateral approach to the ankle is also performed to explore the anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Ankle Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy is done to visualize the internal structures and to assess medial and lateral ankle stability.5

After visual evaluation of the ligaments, test lateral and medial ligament stability by applying gentle varus, valgus, and anterior pull stress to the ankle joint under arthroscopic control.

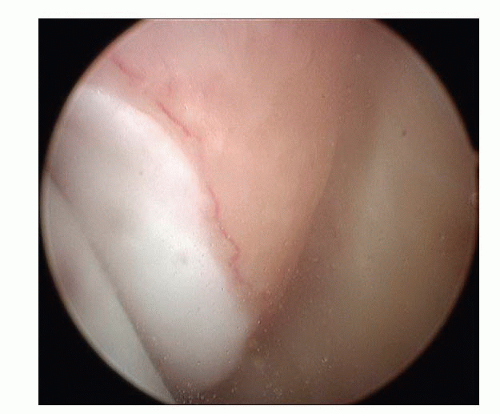

Ligament lesions are graded as distended if the ligament is thinned or elongated and as ruptured if continuity is lost.8 Most ligament tears are located on the proximal insertion; this is best seen by a completely free insertion area of the ligament on the malleoli (TECH FIG 1).

As the foot is everted and pronated, the deltoid ligament is considered incompetent when it is tensioned, but obviously, no strong medial buttress is created with this maneuver (TECH FIG 2). An excessive lifting away of the talus from the medial malleolus by pulling the foot anteriorly is also considered an indicator of stretching of this ligament.

TECH FIG 1 • Avulsion of the anterior superficial layers from the medial malleolus. Arthroscopy typically reveals a completely free insertion area of the ligament on the medial malleolus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access