Medial and Lateral Epicondylitis: Open Treatment

Usha S. Mani MD

Adrienne J. Towsen MD

Michael G. Ciccotti MD

History of the Technique

Epicondylitis is one of the most common conditions to affect the elbow in adults. The term epicondylitis does not accurately reflect the disease process, which histologically involves tendon degeneration and an incomplete reparative process rather than inflammatory changes. The term tendinosis is more appropriate when describing this disorder.1

The majority of literature available on epicondylitis strongly supports nonsurgical treatment. Greater than 90% of patients with either medial or lateral disease will improve with conservative measures such as anti-inflammatory medications, activity modification, counterforce bracing, local corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy modalities. The small percentage of patients who do not respond to a focused nonsurgical treatment program become candidates for surgical treatment.1,2,3

Historically, a multitude of procedures have been proposed over the past 75 years for the treatment of refractory epicondylitis. Lateral epicondylitis has received the majority of that focus. In 1927, Hohmann described release of the common extensor origin at the lateral epicondyle.4 Since then, there have been modifications of this original description, as well as alternative procedures put forth in the literature. Release of the extensor origin with or without release of the annular ligament, percutaneous release of the common extensor origin, lengthening of the distal extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon, arthroscopic debridement of the tendon, and, most recently, the use of radiofrequency probes through a limited exposure are all documented ways of surgically handling this problem.5,6 There has been less literature devoted to medial epicondylitis; however, it is generally agreed that the same surgical principles used on the lateral side apply to the medial side.

Currently, the most widely used open procedure both laterally and medially involves the general principles of exposing the tendon, excising the pathologic portion, repairing the resultant defect, and reattaching any elevated tendon origin back to the epicondyle. In this chapter we will describe the technique in detail from indications to intraoperative pearls and pitfalls to postoperative rehabilitation and finally outcomes and future directions.

Indications and Contraindications

As previously mentioned, the majority of patients with epicondylitis about the elbow do not require surgical management. When evaluating a patient for either medial or lateral elbow pain, it is imperative to rule out other problems that may produce symptoms similar to epicondylitis. The differential diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis most commonly includes posterior interosseous nerve entrapment, radiocapitellar joint disease, including arthrosis and osteochondritis dessicans, and radiculopathy due to cervical spine disease. Primary ulnar neuropathy and ulnar collateral ligament pathology are other etiologies for medial elbow symptoms that can mimic medial epicondylitis. Once diagnosed with medial or lateral epicondylitis, a supervised course of nonoperative treatment should be carried out for a minimum of 3 to 6 months.1,7

Nonoperative treatment begins with activity modification. It is often necessary to completely refrain from the offending activity for a short period of time. It is also beneficial to examine technique and equipment use, especially with racket sports. Possible alterations in one or both of these areas may prevent recurrent episodes of epicondylitis. Although the disease process is more of a tendinosis and not a tendonitis, a 2- to 4-week course of anti-inflammatory medication is effective in many patients for the concomitant synovitis. If there has been night pain or no response to anti-inflammatories,

then a cortisone injection may also be provided. The use of ice and counterforce braces may also be helpful as part of the treatment regimen. Patients are initiated on a course of physical therapy for flexibility and strengthening. Modalities such as ultrasound, iontophoresis, or electrical stimulation can provide added benefit.2,8

then a cortisone injection may also be provided. The use of ice and counterforce braces may also be helpful as part of the treatment regimen. Patients are initiated on a course of physical therapy for flexibility and strengthening. Modalities such as ultrasound, iontophoresis, or electrical stimulation can provide added benefit.2,8

If a patient has had all other possible etiologies ruled out and exhibits persistent symptoms that interfere with activities of daily living or optimal athletic performance, in spite of such a focused nonsurgical program for 3 to 4 months, then surgery should be considered. Those patients who have structural injury such as clinically or radiographically identified tearing or detachment of the extensor or flexor-pronator origins may require surgery sooner.

Surgical Techniques

Our preferred open surgical treatment for lateral and medial epicondylitis involves the same general principles of removing degenerative tendon, providing an environment for healing tissue, and restoring the tendon origin anatomically.

Lateral Epicondylitis

The choice of anesthetic varies from patient to patient; however, if the patient’s medical history allows, general anesthesia is utilized. The use of regional anesthesia may not allow a thorough postoperative neurologic check. The patient is positioned supine with the arm on an arm board or hand table. A tourniquet is applied to the upper arm as high as possible. The arm is draped freely in a standard sterile fashion.

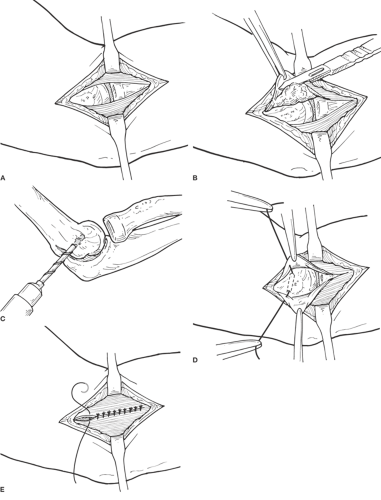

A 5- to 7-cm curvilinear incision is made, just anterior to the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 28-1A,B,C,D). There should be equal exposure proximal and distal to the level of the epicondyle. Anterior and posterior subcutaneous flaps are then sharply developed. Care should be taken to avoid branches of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree