Mechanical Disorders of the Knee

Dennis W. Boulware

Introduction

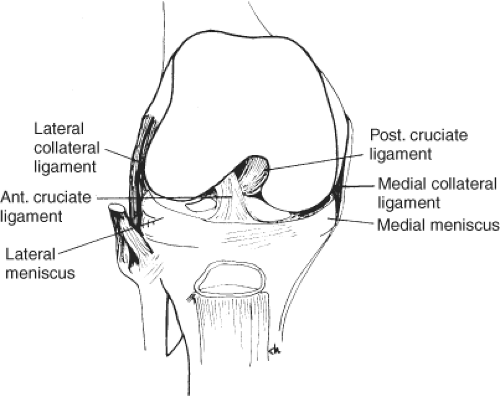

Mechanical disorders of the knee include clinical conditions caused by malfunction, trauma, or degeneration of a specific intra-articular and/or extra-articular component of the knee interfering with normal knee function. An internal derangement of the knee commonly refers to a disorder of the intra-articular components, more commonly the articular cartilage, meniscus fibrocartilage, collateral ligaments, or cruciate ligaments (Fig. 6.1). Disorders of extra-articular components of the knee joint include patellofemoral malalignment and insufficiency of the quadriceps or hamstring muscle groups, and are considered as mechanical disorders too.

Significant mechanical disorders of the knee causing instability, if continued unabated, eventually lead to osteoarthritis. Experimental animal models of osteoarthritis typically involve initiating an internal derangement of the joint, followed by continued use of the limb. The most common models of experimental osteoarthritis include partial medial meniscectomy or transection of the anterior cruciate ligament. Injuries of the medial meniscus and anterior cruciate ligament are common and as our population ages and becomes more engaged in recreational and sports-related activities, mechanical disorders of the knee will become more prevalent and, if not recognized early, will result in an increased prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Clinical Presentation

Most knee pain results from disruption of one of the many components that comprise a functional knee joint. These components include the articular hyaline cartilage, the supporting meniscal fibrocartilage, and the various ligaments. An understanding of the anatomy and biomechanics of the knee coupled with a focused physical examination of various components of the knee usually identify the cause of pain. This chapter focuses on derangements of the menisci, ligaments, and patellofemoral alignment as a cause of knee pain since they are the most common mechanical disorders of the knee.

Clinical Points

Mechanical disorders can lead to knee instability and premature osteoarthritis.

The physical examination of the knee is essential in identifying the cause.

Buckling of a painful knee is common and not always associated with a torn meniscus.

Chronic meniscal tears are commonly associated with osteoarthritis.

In general, patients complain of knee pain primarily with use and further history is of limited value in identifying the mechanical disorder other than the

acuity of the pain and an identifiable precipitating event. Buckling of the knee with weight-bearing is associated with all types of internal derangements and more commonly occurs as a reflexive muscular relaxation to the sudden onset of pain, causing the knee to “give way.” True locking of the knee, though, should focus the clinician on a torn and displaced meniscus getting entrapped within the joint.

acuity of the pain and an identifiable precipitating event. Buckling of the knee with weight-bearing is associated with all types of internal derangements and more commonly occurs as a reflexive muscular relaxation to the sudden onset of pain, causing the knee to “give way.” True locking of the knee, though, should focus the clinician on a torn and displaced meniscus getting entrapped within the joint.

Acute injuries with identifiable precipitating events such as trauma or injury commonly involve meniscus or ligament damage with immediate pain, and continued pain with weight-bearing or use of the limb and often limited range of motion secondary to the pain. If the acute injury resulted in a displacement of the torn meniscus, patients often complain of a painful “catching” or “popping” sensation in the knee. Large sudden effusions suggest a hemarthrosis that is more commonly seen with torn ligaments as opposed to a torn meniscus. Ligaments are vascularized structures, and damage to the ligament usually results in a hemarthrosis. Effusions that occur later can be seen in either ligament or meniscus damage. An examination of the joint will help identify the source of damage.

The absence of an identifiable precipitating event suggests a degenerative process that eventually reached a tipping point causing clinical symptoms. Particularly with a chronic tear of the meniscus, there is usually less pain than an acute tear, and there is frequently a lack of any recognizable precipitating event. Chronic meniscal tears are typically associated with osteoarthritis, and a precipitating cause may be as simple as a squatting and twisting maneuver or a simple misstep. Chronic pain with use of the knee and episodic effusions of the knee often precede the patient’s eventual visit to see the physician. With chronic derangements, limitation in range of motion is less of a prominent feature than with acute and displaced tears.

Complaints of pain with use are common in all mechanical disorders of the knee, but pain felt in the anterior of the knee or with descending stairs or inclined surfaces as opposed to ascending stairs or descending surfaces are common complaints of patellofemoral compartment problems. Patients with patellofemoral pain often complain of pain after prolonged periods of immobility with the knee in flexed positions such as sitting at a desk or riding in an automobile; when resuming activity again, the condition will often cause pain for a brief period of time, such as the first few steps after resuming a standing position.

Pain felt in the popliteal area is typically due to effusions distending the joint capsule or due to an effusion causing a popliteal cyst to fill, causing pain from distention of the cyst. Popliteal pain does not often identify the source of the mechanical disorder causing the increased synovial fluid to accumulate as much as reflect distention of the popliteal cyst or joint capsule. Popliteal cysts are common in many individuals and communicate with the joint space, but typically are not fluid-filled except when the pressure in the synovial space increases and synovial fluid is pumped from the joint into the popliteal cyst. The communication between the cyst and joint space does not always allow the fluid to return to the joint space, but will eventually be reabsorbed when the joint space pressure returns to normal and no further fluid is pumped in the popliteal cyst.

Worse pain with descending stairs or declining surfaces suggests patellofemoral disease.

Testing for instability is critical in ligamentous lesions.

Displaced meniscal fragments can become entrapped and lock the knee.

Reserve imaging studies for recurrent or recalcitrant knee pain.

Physical Findings

The physical examination is the most helpful in the clinical evaluation of the patient as various maneuvers allow the clinician to test each component of

the knee, allowing identification of a dysfunctional component or source of the pain. In addition to these provocative maneuvers, the examination should assess for passive ranges of motion and the presence of effusions.

the knee, allowing identification of a dysfunctional component or source of the pain. In addition to these provocative maneuvers, the examination should assess for passive ranges of motion and the presence of effusions.

Positioning the patient in a supine posture will aide in getting the patient to relax which will be essential in measuring the full passive range of motion. In measuring passive range of motion, the femur is used as the reference arm of the knee and the normal range of extension is measured as 0 degree with the knee extending the same trajectory as the femur. The inability of the knee to position into full extension should be recorded in degrees relative to the femur. An acute loss of full extension may reflect a displaced meniscus, a large joint effusion distending the knee joint capsule, or a distended popliteal cyst. A chronic loss of full extension typically reflects a longstanding osteophyte suggesting a degenerative process. With the patient relaxed as much as possible, passive full flexion in the patient should be measured. Normally, the knee will have 0 degree of extension and 140 degrees of flexion. As in measuring extension, the acute loss of full flexion may reflect a displaced meniscus; a large joint effusion distending the knee joint capsule or a distended popliteal cyst and a chronic loss will suggest an osteophyte indicating a degenerative process. Joint effusions often impair full passive range of motion and usually correlate with the severity of inflammation within the knee joint.

Figure 6.2 McMurray test. From Berg D, Worzala K. Atlas of Adult Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|