Chapter 19 Manipulation, Traction, And Massage

The “laying on of hands” has been a diagnostic and therapeutic modality used since antiquity, and has created a special bond between practitioner and patient. Over the millennia a multitude of “hands-on” techniques have been used to treat human suffering. Although they have waxed and waned in popularity, these modalities and techniques have been gaining acceptance in recent years. These methods have been used as an “aggressive” nonsurgical approach to the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders, particularly neck and low back pain. Neck and low back pain have reached epidemic proportions in many industrialized nations. It has been estimated that approximately 80% of all adults will experience low back pain in their lives, and approximately 50% of individuals will experience neck pain in their lives.58 This escalation of axial pain has created great financial ramifications for society. In recent years, there has been an attempt to reduce morbidity and improve the cost-effectiveness of therapy options.

Manipulation

Definition and Goals

The International Federation of Manual Medicine3 defines manipulation as “the use of the hands in the patient management process using instructions and maneuvers to maintain maximal, painless movement of the musculoskeletal system in postural balance.” The goal of manipulation or manual medicine is to help maintain optimal body mechanics and to improve motion in restricted areas. Enhancing maximal, pain-free movement in a balanced posture and optimizing function are major goals.43,69,128 These goals are accomplished by treatments that attempt to restore the mechanical function of a joint and normalize altered reflex patterns,107,128 as evidenced by optimal range of motion, body symmetry, and tissue texture. The indications for successful use of manual medicine techniques are determined by structural evaluation before and after treatment.69,103

Manual medicine can involve manipulation of spinal and peripheral joints as well as myofascial tissues (muscles and fascia). The most fundamental use of manual medicine is to relieve motion restriction and improve motion asymmetry. Improved motion and flexibility are helpful in restoring optimal muscle function and ease of motion. A decrease in pain is often associated with restoration of normal motion. Sometimes therapy is directed at reduction of afferent (nociceptive) input to the spinal cord. Endorphin release increases pain threshold and reduces pain severity.68,87,107

Manual medicine continues to be widely practiced and is in high demand by patients.44 It is estimated that 12 to 17.6 million Americans130,135 receive manipulations each year, with a high degree of patient satisfaction.26

Overview of Various Types of Manual Medicine

Manual medicine techniques can be classified in different ways. Techniques may be classified as soft tissue technique, articulatory technique, or specific joint mobilization.103 The objective to be accomplished can be used as a type of technique, such as movement of fluids. The terms direct and indirect are used to classify technique, with several types of technique in each category. Direct technique means that the practitioner moves the body part(s) in the direction of the restrictive barrier. Indirect technique means the practitioner moves the body part away from the restrictive barrier.

Direct techniques include the following:

Indirect techniques include the following:

Historical Perspective and Practitioners

Manual medicine has regained popularity over the past 30 to 40 years, but its practice dates back to the time of Hippocrates (460 to 377 BC) and Galen (131 to 202 BC).73,76 Many other physicians (e.g., Sydenham, Hahnemann, Boerhaave, and Shultes) deviated from the traditional disease-oriented form of medicine during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,76 but manual medicine fell out of favor until the nineteenth century. The pioneers of manual medicine at that time included the “bonesetters” of England—Richard Hutton, Wharton Hood, and Sir Herbert Baker23,76—followed by Andrew Taylor Still, the founder of osteopathic medicine in 1874,69 and Daniel David Palmer, the founder of chiropractic medicine in 1895.69,76

Still’s philosophy stressed wellness and wholeness of the body.110 Osteopathic principles describe the body as a unit that possesses self-healing mechanisms, and that structure and function are interrelated. All of these principles are incorporated into practice.164 Manual medicine was and is an integral part of this treatment.

“Traditional” medical professionals have also shown interest in manual medicine. Mennell119 and his son John M. Mennell,119 as well as Edgar and James Cyriax,37 have espoused the use of joint manipulation within the British medical community. Beginning in the 1940s, James Cyriax,37 a British orthopedic surgeon, published several works related to manipulation, incorporating massage, traction, and injections. Travell’s use of manual techniques for examination purposes has been widely accepted.158 Today, the Fédé ration Internationale de Mé decine Manuelle represents manual medicine practitioners throughout the world.

Barrier Concept

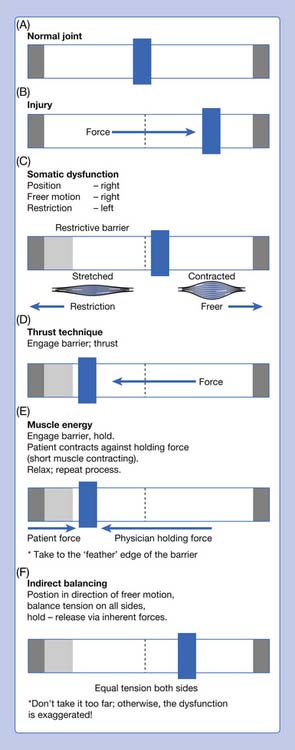

The barrier concept recognizes limitation of motion of a normal joint in which asymmetric motion is present. Motion is relatively free in one direction, with loss of some motion in the other direction. Motion loss occurs within the normal range of motion for that joint (Figure 19-1).

Normal and Abnormal Coupled Spinal Motion

Motion of the spine follows principles of spinal motion often attributed to Harrison H. Fryette.57 Flexion (forward bending) and extension (backward bending) are sagittal plane motions and are not coupled. However, rotation and side bending are coupled. The amount of pure rotation or pure side bending of spinal joints is limited. Rotation and side bending occur together in normal spinal joints. Fryette stated that when there is an absence of marked flexion or extension (termed neutral) and side bending is introduced, a group of vertebrae rotate into the produced convexity, with maximum rotation at the apex. Rotation and side bending occur to opposite sides when compared with the original starting position. This is sometimes referred to as neutral mechanics or type 1 dysfunction. Nonneutral or type 2 mechanics involve a component of flexion or extension with rotation and side bending to the same side. This is usually single-segment motion, although several segments may be involved. The cervical spine (C2–C7) exhibits rotation and side bending to the same side whether flexed, neutral, or extended.

Nomenclature

Somatic Dysfunction

Manual medicine or manipulation involves treating motion restrictions. Nomenclature to describe this motion restriction has changed. The term manipulatable lesion is a generic term to describe musculoskeletal dysfunction that might respond to manipulation. Previous terms included osteopathic lesion, subluxation, joint blockage, loss of joint play, and joint dysfunction.106,107,128

Somatic dysfunction is a diagnostic term listed in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision classification of diagnoses. It is defined as impaired or altered function of related components of the somatic (body framework) system: skeletal, arthrodial, and myofascial structures, and related vascular, lymphatic, and neural elements.69 Somatic dysfunction represents a critical concept in manipulative medicine. Somatic dysfunction is diagnosed by palpation. Dysfunctions that are palpated include changes in tissue texture, increased sensitivity to touch (hyperalgesia), altered ease or range of motion, and anatomic asymmetry or positional change.166

The Glossary of Osteopathic Terminology164 describes three ways of naming somatic dysfunction:

Segmental dysfunctions are named for the anterior superior portion of the upper vertebrae in relation to the lower (e.g., T3 in relation to T4). Nomenclature can be expanded to include the three planes of motion (e.g., “T3 flexed, rotated, and side bent right”). Group curves as in scoliosis are traditionally named for the convex side. For example, a right thoracic curve is a “thoracic curve convex right.” It can also be termed dextroscoliosis.

Physiologic Rationale for Manual Therapies

Gamma System

Two types of motor neurons exit the spinal cord through the ventral rami to innervate skeletal muscle. Alpha motor neurons innervate large skeletal muscle fibers. A motor unit consists of a single alpha motor neuron and the skeletal muscle fibers it innervates. Gamma motor neurons innervate intrafusal fibers in the muscle spindle. These intrafusal fibers have annulospiral and flower spray endings that report information about muscle length or rate of change of muscle length. Increased gamma activity of the muscle spindles results in increased alpha motor neuron activity to extrafusal fibers of skeletal muscle. From a clinical perspective, if a muscle is too tight, the practitioner attempts to bring about muscle relaxation. Decreasing gamma gain activity is one mechanism that results in muscle relaxation.42

Spinal Facilitation

Early research studies on facilitation demonstrate how behavior of the spinal cord is altered. Korr106 applied pressure to spinous processes and measured how much pressure was necessary to produce an electromyographic response in the muscle. A facilitated segment requires less pressure to produce a response. The sympathetic nervous system innervates sweat glands (although this is a cholinergic response). Spinal cord facilitation results in increased sweating at the segmental level. Other factors affect spinal cord behavior. Patterson132 demonstrated that the spinal cord has “memory” that results in conditioned reflexes. If a stimulus is maintained for a certain period, then removal of the stimulus does not eliminate the response. At one time it was considered that the amount of afferent input produced facilitation. However, when the mix of afferent input is altered, it is as if the cord listens more carefully to the signals (sensitization) coming in. Afferent input from dysfunctional visceral structures produces viscerosomatic reflexes and facilitation.

What maintains facilitation? At one time it was thought that the muscle spindle with increased gamma tone was the basic factor in maintaining facilitation. Subsequent studies have shown that nociception maintains facilitation.160 Animal studies have been conducted in which afferent fibers from the spindle to the cord were cut, and facilitation continued. Blocking nociceptive input tends to cause facilitation to disappear.

The previous discussion of neurophysiology only scratches the surface. The spinal cord is connected to the brain. There is a vertical component to nerve conduction to and from the brain, as well as a horizontal component between dorsal and ventral roots. There is a neuroendocrine immune system at work. Neuropeptides can sensitize primary afferent fibers, as well as fibers within the central nervous system. The practitioner needs to understand the physiologic mechanisms behind muscle tightness, motion restriction, nociception, and inflammation that create dysfunction. Manipulation is one of the treatments used to decrease dysfunction and help the patient. Much of the data necessary to use manipulation effectively come from palpatory assessment rather than high-tech testing. Simple soft tissue techniques are designed to relax tight muscles and fascia. Forces applied too fast or too heavy will cause the muscle to fight back. The response to the application of force is continuously monitored to make sure the muscle relaxes. The focus of the practitioner during treatment is to assess how the patient is responding to the treatment rather than whether the gamma gain has been reduced. Figure 19-1 illustrates how a shortened and contracted muscle can restrict motion.

Indications and Goals of Treatment

Somatic dysfunction can coexist with “orthopedic disease” (e.g., osteoarthritis or disk disease).63 Manual medicine treatment helps the somatic dysfunction and helps the patient, but the underlying orthopedic disease process will remain. Other confounding factors are causes for the somatic dysfunction. The patient might have an anatomic short leg, which will continue to maintain sacroiliac and low back dysfunction. Certain activities might be too stressful for the musculoskeletal system. In a controlled study of low back pain, it is impossible to control for these confounding factors.

Examination and Diagnosis

Physical examination includes acquiring a sufficient physical examination database to enable appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Patients in the emergency department routinely undergo examination of the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT), heart, lungs, and abdomen. The musculoskeletal examination goes beyond looking for problems in a system. The practitioner should look for clues about the health status and function of the patient. Is there a somatic component(s) to the patient’s problem(s)? The musculoskeletal screening examination looks at gait, posture, and symmetry or asymmetry. This is ordinarily done with the patient standing. A standardized 12 step biomechanical screening examination may be done,69 or the screening examination may be nonstandard, using a systematic approach to evaluate all body regions. This examination can be integrated into a comprehensive physical examination.

Palpation for Tissue Texture Abnormality

Paraspinal viscerosomatic reflexes have palpatory qualities that are characteristic and allow the experienced clinician to conclude that these changes are due to visceral disturbances. The maximum intensity of the findings is reported to be at the costotransverse and rib angle areas. The greatest number of findings is in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Kimberly103 described these findings as “minimal motion loss lesions.” Chronic viscerosomatic findings take on the characteristics of any chronic somatic dysfunction. Clinically, findings present as an acute exacerbation of a chronic problem, with the superficial puffiness of acute change and the motion restriction of chronic somatic dysfunction. In the interscapular area, failure to move the scapula laterally to allow adequate palpation of the rib angles will result in failure to detect musculoskeletal findings.

Motion Testing

Types of motion testing include the following:

Functional Technique Assessment

The tissues on either side of the dysfunction are palpated for tension with the joint close to the midline and not close to the barriers. Tension is evaluated in the three cardinal planes, three translations, and respiration.19,93 The position for indirect treatment involves equal tension on both sides.

Assessment of Fascia

Assessment of fascia starts with placement of the hands to perceive the combined vector force in the tissue.45 Hand placement varies depending on the area to be assessed and treated. Assessment of an extremity would start with hand placement proximal and distal to the area. An example of this would be the assessment of the forearm. One hand grasps the patient’s hand and the other hand grasps the proximal forearm near the elbow.

Types of Technique

Direct Techniques

Articulatory Treatment

This procedure moves a joint back and forth repeatedly to increase freedom of range of motion. Articulatory treatment may be classified as a low-velocity, high-amplitude approach. Sometimes articulatory treatment is a form of soft tissue treatment in which the only way to access deep muscles is to move origin and insertion (see Figure 19-2). Articulatory treatment is very useful for stiff joints and for older patients. It might be the only form of treatment applicable for some patients. There are many modifications to articulatory technique.

Mobilization With Impulse (Thrust; High Velocity, Low Amplitude)

A diagnosis of motion restriction is essential before application of thrust technique, and this diagnosis should incorporate the three planes of motion: flexion-extension, rotation, and side bending. The first principle of thrust technique is to engage the barrier. With an accurate diagnosis, engaging the barrier is specific. The barrier must feel solid, not rubbery. A thrust should not be applied if the barrier does not feel solid. Instead of addressing the restriction of motion of the joint, the force is dissipated by muscles and fascia. The thrust must be low amplitude, meaning a very short distance. The thrust should be high velocity (Figures 19-3 through 19-5). There is no place for high-velocity, high-amplitude technique.

Muscle Energy: Direct Isometric Types

Muscle energy technique65,123 was introduced by Fred Mitchell, Sr.121 Muscle energy technique involves the patient voluntarily moving the body as specifically directed by the practitioner. This directed patient action is from a precisely controlled position against a defined resistance by the practitioner. The initial classification of muscle energy techniques was based on whether the force was equal (isometric), greater (isotonic), or less (isolytic) than the patient force. Most muscle energy techniques used by physicians are direct isometric techniques. This technique has been used extensively by therapists and is often referred to as contract relax technique.

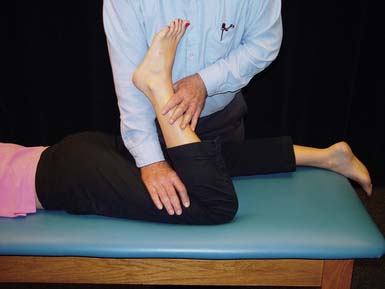

Muscle energy technique requires a specific diagnosis. The first step is moving the dysfunctional component into the restrictive barrier. Fred Mitchell, Jr,122 emphasizes that the practitioner moves the dysfunctional component to the “feather edge” of the barrier. The practitioner holds this position and instructs the patient to contract against the holding force. The patient controls the amount of force, so injury is not likely. Additionally, the manner in which the practitioner holds the patient position suggests the amount of force. A heavy-handed vice grip will suggest more force than a lighter touch. The muscle contraction is held for 3 to 5 seconds. Then there is a period of relaxation, sometimes termed postisometric relaxation. The practitioner then reengages a new barrier, and the process is repeated several times. If there is no further increase in the range of motion, it is time to stop. Three repetitions are the usual number, followed by reassessment.

Indirect Techniques

Strain-Counterstrain

Counterstrain is a type of manipulative treatment that uses spontaneous release by positioning, and uses tender points serving as a monitor to achieve the proper position. Lawrence Jones, DO,94 developed this method of treatment. Counterstrain is classified as an indirect technique. The objective is to relieve painful dysfunction through a reduction of inappropriate afferent proprioception activity. Referring to Figure 19-1, the shortened muscle remains shortened because of inappropriate proprioceptive activity. Tender points are located in the muscle belly, tendon (usually at or near the bony attachment of the tendon), or dermatome of the shortened muscle. Treatment position further shortens the short muscle, as a “counterstrain” is applied to the originally strained muscle on the other side. The neurophysiologic mechanism is based on the fact that shortening the muscle quiets the muscle and breaks into the inappropriate strain reflex.

Tender points are related to specific dysfunctions. The practitioner must know where to look for these specific points.95 For example, if the patient has a dysfunction at L3 that is flexed, rotated, and side bent left, an anterior lumbar tender point is located in the abdominal wall in the vicinity of the anterior inferior iliac spine. The use of counterstrain requires a structural evaluation and assessment for tender points. Tender points are tissue areas that are tender to palpation. They are sometimes described as “pealike” areas of tension. The common denominator is the tissue change and tenderness.

Treatment involves identifying the tender point, maintaining a palpating finger on the tender point, and placing the patient in a position so that tenderness in this point is eliminated or reduced significantly. This position is in a pain-free direction of ease. Also, the position places the patient in the original position of injury. Counterstrain is not a form of acupressure. The monitoring finger continues to palpate and assess the point, but pressure is not applied. The amount of time that the treatment position is held is 90 seconds, 120 seconds for ribs. It is essential that the patient be slowly returned from the treatment position to the starting point. The patient should remain passive during the entire process. After return, the tender point is reassessed. If the physician’s palpating finger stays on the tender point, and tenderness is now absent, both practitioner and patient know that a change was made (Figure 19-6).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree