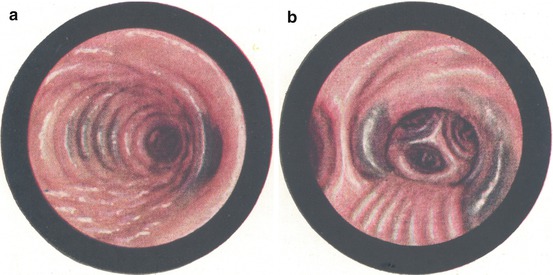

Fig. 19.1

Ochronosis and its location in the cartilaginous skeleton of the lower respiratory tract: (a) The cartilaginous skeleton from the front side – the places with considerable ochronotic colouration are marked with blue colour. (b) The same changes on larynx rear side. Pigmentation was not apparent at other places of the cartilaginous skeleton, but it does not mean that it could not be present there; it only could not be demonstrated yet

In literary sources, we found the case of Gross and Allard (1907) who found, during autopsy, typical colouration of cartilages of the larynx, trachea and bronchial tree in alkaptonuric patient who died of sepsis. Besides the colouration of auricles, they found dark-coloured, brittle laryngeal cartilages similar to burnt wood. Histologically, it was confirmed that the changes were caused by deposited pigment in cartilaginous tissue. Ochronosis was also histologically confirmed in the trachea and bronchi. We quote the findings in the trachea: ‘Dark brown pigment is found in perichondral tissue as well as in connective tissue, mostly in the form of narrow bands and rarely accumulated in larger conglomerates’. Excerpt from lung histology: ‘Small bronchopneumonic foci sporadically, oedema sporadically. Granules of dark pigment around bronchi can be found at some places’. It means that the pigment was found around very small bronchi going to the lung parenchyma. All tracheal and bronchial tree rings macroscopically had black colouration. In this case, ochronosis completely affected the cartilaginous skeleton of the lower respiratory tract as well as larynx. Histological examination was not performed either from the larynx or larger bronchi.

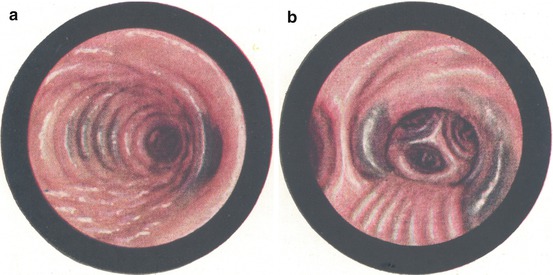

It can be seen from autopsy findings of Švejda’s case (1945) that ochronosis can affect the whole cartilaginous system of the lower respiratory tract. We have always seen inhomogeneous colouration of the respiratory tract in the larynx as well as in the trachea and bronchi. We found colouration of cartilaginous rings in the bronchial tree anywhere in the visual field, but the most intense colouration was always present at the places of lobar lines of division in segmental bronchi. It is probable that these changes are repeated in further peripheral parts, to sub-segments, etc. (Fig. 19.2a, b).

Fig. 19.2

Ochronosis in the bronchial tree. (a) The right main bronchus with the origin of the upper lobar bronchus. Colouration at the division line of upper and connecting part and on internal wall of the main bronchus. (b) The right upper bronchus with segmental trifurcation and several subsegmental bronchi. Colouration is usually located at division lines

Naturally, intensity of colouration is various, and thus, the quality or colouration tone partially changes from slight bluish tinge to deep green-blue colour. Pigment patches never have sharp margins, they are not well demarcated, and they fade away in surrounding area. If they have a small intensity, they are exclusively limited to cartilaginous rings. In case of deep colouration, they also overlap to inter-cartilaginous connective tissue membranes. Even in case of intense pigmentation, we have never seen colouration of the paries membranaceus of the trachea and main bronchi. These characteristic properties of ochronotic pigmentation have to be known to distinguish from other pigmentations that can be encountered on mucosa and submucous tissues in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract. We can see physiologic as well as pathological pigmentations in the bronchial tree. Pathological pigmentations can be seen in mercury and bismuth poisoning, haemosiderosis, Addison’s disease, pernicious anaemia, melanosarcoma, malaria, icterus, etc. Some of them can be recognised easily; other ones can be hard to be diagnosed. A lot of attention has to be paid to distinguish ochronosis from anthracosis. Anthracotic colouration is always more intense, black, well demarcated and located mostly outside cartilaginous rings. Typical location is in lymphatic nodes, blood vessels and their adjacent area.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree