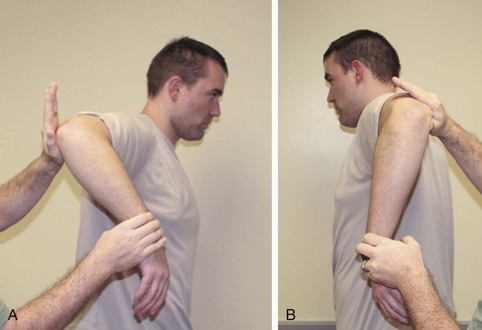

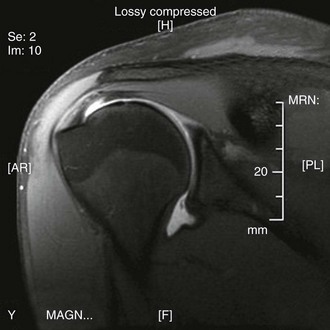

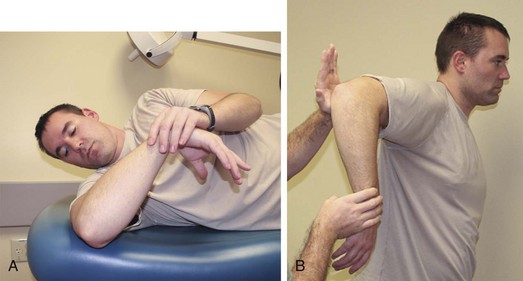

Chapter 7 The throwing shoulder continues to be a challenge to manage and treat. The demands placed on the shoulder by overhead athletes produce a unique pathophysiology most evident in elite throwers. The throwing shoulder exerts up to 7000 degrees/sec rotational velocity, reportedly the fastest movement in sports.1 As a result, throwing shoulders have been noted to exhibit adaptations including increased external rotation, decreased internal rotation, increased humeral and glenoid retroversion, and anterior capsular laxity. The combination of these demands and adaptations has created common pathologic lesions in the shoulder such as partial-thickness articular rotator cuff tears, anterior capsular laxity and pseudolaxity, posterior-inferior capsular contracture, posterior and posterosuperior labral injury, biceps tendon pathology, and scapular dyskinesis.2 Multiple theories about the cause of the dysfunctional throwing shoulder have been presented throughout the years. In 1959, Bennett described a posteroinferior glenoid exostosis as the inciting pathology for pain in the professional pitcher secondary to repetitive traction on the posterior capsule and triceps tendon.3 This theory has since fallen out of favor, although his focus on the posterior capsule would lay the foundation for future work in treating the throwing shoulder. Neer described impingement syndrome in 1972, and for a time this was considered a likely cause of the dysfunctional throwing shoulder.4 The patient’s complaints and physical examination findings had much overlap with those of impingement, and it was clear that the rotator cuff was often involved. However, Tibone and colleagues in 1985 reported on a series of shoulders treated with acromioplasty for impingement, including the shoulders of 18 throwers. Despite good pain relief, only 4 of the 18 returned to throwing.5 In the 1990s, Jobe introduced the concept of secondary impingement, which proposed that anterior shoulder instability brought on by repetitive stretching of the anterior capsule was the cause of the impingement. Jobe’s 1991 article6 was associated with excellent pain relief, but return to throwing remained elusive. By the late 1990s, arthroscopy had become an important adjunctive tool in evaluating the throwing shoulder. At that time both Jobe and Walch separately described impingement of the cuff on the posterosuperior glenoid or “internal impingement.” Jobe continued to attribute it to anterior laxity or “microinstability” as a result of repetitive forces in an abducted and maximally externally rotated position. Paley and colleagues7 and Conway8 both demonstrated that anterior instability was very common in throwers and contributed to internal impingement. However, Walch reported on arthroscopic examination of 16 throwers with internal impingement but no instability, and described the visualization of the rotator cuff impinging in an abducted and externally rotated position leading to partial-thickness cuff tears and posterior capsular lesions.9 Other studies have confirmed symptomatic internal impingement without anterior instability and a lack of laxity between throwing and nonthrowing shoulders in pitchers.10 In 2003, Burkhart and colleagues reported that internal impingement is actually a physiologic occurrence and that contracture of the posteroinferior capsule shifting the humerus posterosuperiorly is the primary pathology in the disabled throwing shoulder.2 The authors noted that the resulting glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) is the hallmark of the at-risk throwing shoulder. Other studies have confirmed the high prevalence of GIRD in throwing shoulders, its increased association with shoulder pathology, and resolution of symptoms with correction of GIRD.2,11,12 However, there is evidence contrary to this idea as well. Huffman and colleagues, the same group that performed the biomechanical study that initially supported GIRD, revised their model in 2006 and showed that obligate translation with simulated posterior capsular contracture was in fact anterior and inferior and occurred during follow-through and not cocking.13 In addition, GIRD has been noted to be present in 40% of asymptomatic throwers.14 In fact, the disabled throwing shoulder may well be caused by a spectrum of conditions resulting from the adaptations required when variable anatomy and physiology are subjected to the extreme demands of throwing an object beyond physiologic limits. History and Physical Examination The dysfunctional throwing shoulder may manifest classically with posterior shoulder pain at the cocking phase of the throwing motion or during follow-through. Some patients, however, may describe a loss of control or velocity or the feeling of a “dead arm.” The physical examination may reveal tenderness to palpation, increased external rotation with decreased internal rotation,15 instability or laxity, and positive posterior impingement test results,16 as well as more traditional impingement signs. Decreased internal rotation of more than 20 degrees compared with the contralateral side, especially in the setting of a decreased total arc of motion, is suggestive of GIRD (Fig. 7-1) and should raise the suspicion for the examiner. With this increased suspicion, the examiner must pay particular attention to the core strength of the athlete, the scapula, and associated shoulder pathology. SICK scapula syndrome (scapular malposition, inferior medial border prominence, coracoid pain and malposition, and dyskinesis of scapular movement), or scapular dyskinesia, usually manifests with static and dynamic scapular malposition evident when the patient is asked to repeatedly raise and lower the arms or engage the dynamic stabilizers of the scapula.17 Associated pathology such as shoulder microinstability, as evidenced by a positive result on relocation test for pain, superior labral tears suspected with a positive active compression test result, and pain with a sleeper stretch are all keys to the physical examination. Although standard radiographs should be included in the workup of the disabled throwing shoulder, they are usually normal. The cornerstone of radiographic evaluation remains magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or even magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA), which can increase the study’s accuracy in detecting labral pathology, rotator cuff and biceps pathology, capsular thickening, bursal pathology, and bony edema (Fig. 7-2). Computed tomography is not a standard method of examination but may be indicated if there is an abnormality on initial radiographic evaluation. Throwing is the culmination of multiple energy transfers from the proximal to distal kinetic chain. Deficits anywhere along this chain can be translated to more distal injury. Therefore, nonoperative management of the disabled throwing shoulder must address all aspects of the kinetic chain, as well as the shoulder itself, to be successful. Hip and leg strength must be maintained, and core strengthening cannot be overemphasized. The scapular platform must be optimized, as it forms the critical transfer between the power created in the core and the speed generated in the shoulder. Specific attention to the shoulder includes treatment of scapular and dynamic stabilizers as well as posterior capsular stretching. SICK scapula syndrome is the manifestation of a dyskinetic platform but can be effectively rehabilitated with retraining of scapular mechanics.17 Rotator cuff weakness is common in the painful throwing shoulder, and cuff strengthening is a mainstay of any nonoperative approach to throwers. Posterior capsular tightness is among the most detrimental adaptations in the thrower but can be effectively treated with stretching techniques such as sleeper stretches, leading to resolution of symptoms (Fig. 7-3). Fortunately, most disabled throwing shoulders respond to this comprehensive approach. Wilk and colleagues12 recently reported on their experience with one Major League Baseball team over 3 years. Although many of the pitchers exhibited GIRD, the vast majority of these cases resolved with a supervised athletic training program. Of the 33 pitchers who sustained shoulder injuries, only seven went on to undergo operative management.

Management of the Throwing Shoulder

Pathology

Preoperative Considerations

Imaging

Nonoperative Management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine