Management of the Soft Tissue with Shoulder Trauma

Scott F. M. Duncan

John W. Sperling

Indications/Contraindications

Shoulder trauma can result in significant soft tissue loss over some of the bony prominences of the shoulder such as the acromion and clavicle. Areas of the scapula can be exposed as well from trauma about the shoulder. Fortunately, the glenohumeral joint itself is covered with a multilayer muscle configuration. If there are concomitant fractures, nerve injuries, or vessel injuries, one must keep in mind not only the pre-existing soft tissue trauma and how to protect the healing of that, but also how to obtain the best exposure to facilitate fixing the concomitant injuries. Open fractures and neurovascular injuries require emergent intervention, or otherwise the extremity may be compromised. In such circumstances, the rescue of the threatened limb takes priority. However, again, one must keep in mind the potential need for soft tissue coverage in these patients. Fortunately, numerous flap options exist about the shoulder for soft tissue coverage (see Chapter 8).

The addition of locking plates, which are fixed angle devices for fixing proximal humerus fractures, has greatly augmented our armamentarium for treating these fractures. In significant injuries, it is not unreasonable to perform a delayed intervention once the soft tissues have been covered or stabilized. Concomitant injuries such as rotator cuff tears can be addressed months down the line, if needed, once the other injuries and soft tissue envelope have finished healing. When the wound bed is grossly purulent, coverage and otherwise operative repair should be delayed until a clean wound can be established. This being said, it is obviously preferable to have all structures fixed prior to any type of soft tissue coverage to minimize injury to the soft tissue flap upon re-operation or re-exploration of the wound.

Preoperative Planning

A thorough examination of the shoulder and the involved extremity as well as a radiographic study of the shoulder are mandatory to recognize soft tissue and bony injuries. Neurovascular injuries may be easily missed if the more distal aspects of the extremity are not examined. Furthermore, radiographic examination must include axillary lateral views to rule out a glenohumeral dislocation. Active flexion, abduction, internal and external rotation should be tested about the shoulder when possible. Active flexion and extension about the elbow, wrist, and fingers will also help delineate more proximal neurovascular compromise. Sensation and motor function of the extremity should be documented. Radial pulses as well as ulnar pulses need to be documented as well as the time for capillary refill.

From a radiographic standpoint in the emergent setting, a computed tomography scan sometimes is required to further delineate the characteristics of bony trauma. Occasionally, an arteriogram may be needed to investigate vascular injuries. The most commonly injured nerve about the shoulder is the axillary nerve, and an examination of deltoid function and shoulder sensation should be performed. When planning the surgical exposure or exposures, one must appreciate what other injuries need to be addressed, if any, and how the incision and exposure will jeopardize any pre-existing skin or muscle trauma. Incisions should be selected that will not compromise the viability of the soft tissue

envelope and that once they have healed will not create a tethering-type scar, resulting in loss of shoulder range of motion.

envelope and that once they have healed will not create a tethering-type scar, resulting in loss of shoulder range of motion.

Surgery

Patient Positioning

We prefer to perform surgery about the shoulder with the patient in a beach-chair position. Depending on the injuries to be addressed, supine and lateral decubitus may be used as well. However, in our experience, the beach-chair position has the advantages of allowing manipulation of the arm as needed to facilitate reduction or retraction as well as providing access to both the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder. These surgeries are usually done under general anesthesia, but postoperative pain management can be enhanced by the administration of interscalene blocks by the anesthesiologist. The patient is brought into the regular operating room where preparation and draping are carried out in the usual sterile fashion and manner. As with any surgery, atraumatic technique should be adhered to in an effort to lessen skin, muscle, and other soft tissue necrosis. Poorly executed shoulder surgery can result in greater functional loss than would have otherwise occurred had no surgical intervention been attempted. However, as with any surgery, risks are involved and nerve and vessel injury can occur. Excessive scarring and postoperative joint contractures may result despite the best surgical techniques.

The beach-chair position facilitates the use of fluoroscopy during the course of the procedure (Fig. 7-1). This flexibility is sometimes needed when attempting to image complex injuries. Sometimes it is necessary to extend the wound of the injury both proximally and distally to provide visibility to the area of trauma. However, most important is that an adequate view of the surgical field be created to avoid the need to perform surgical repairs in a challenged manner through a small wound. In general, we try to avoid “T” extensions of transverse lacerations, but occasionally this may need to be done to gain access to neurovascular structures. Again, the type of shoulder injury will necessitate the surgical approach.

Technique

For proximal humerus fractures, there are two basic approaches. The first is a superior deltoid approach in which a skin incision is made in Langer’s lines just lateral to the anterior lateral aspect of the acromion. This approach allows the deltoid to be split from the edge of the acromion distally for approximately 4 to 5 cm. Again, care must be taken to protect the axillary nerve. Of note is that the deltoid origin is not removed, but there is still exposure of the superior aspect of the proximal humerus. This type of exposure is quite useful for a fixation of greater tuberosity fractures as well as the insertion of intramedullary nailing. In the beach-chair position rotation, flexion, and extension

of the humerus can enhance the exposure of the underlying structures as well as reduction of the fragments.

of the humerus can enhance the exposure of the underlying structures as well as reduction of the fragments.

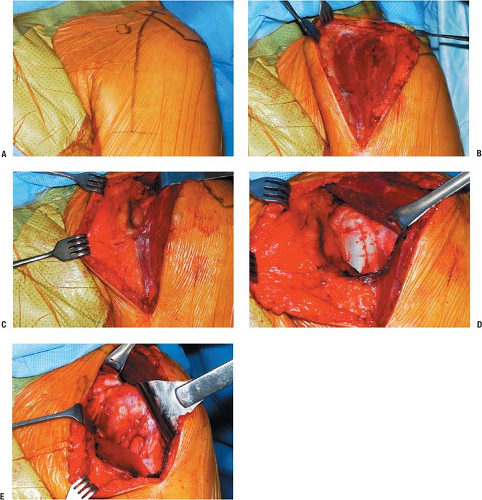

The second approach is a long deltopectoral approach in which both the deltoid origin and insertion are preserved (Fig. 7-2). The skin incision begins just inferior to the clavicle and extends across the coracoid process and down into the area of insertion of the deltoid on the humerus. The cephalic vein should be preserved and retracted either laterally or medially depending on which is easiest for the surgeon. The cephalic vein is less likely to be injured when taken medially, given that over-vigorous retraction on the cephalic vein and deltoids can result in vein injury. If the vein is accidentally transected or significantly injured, either from the trauma or the surgical approach, ligation can be considered. In the deltopectoral approach, if more exposure is needed to gain access to the proximal aspect of the humerus, the superior part of the pectoralis major tendon insertion can be divided. This may need to be done for multipart fractures. In significant trauma injuries, the pectoralis major tendon may be found to be disrupted and should be repaired when possible using nonabsorbable suture and/or suture anchors.

FIGURE 7-2 A: The landmarks of the shoulder are outlined and the incision is marked. B:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|