Management of the Arthritic and Stiff Elbow and Osteochondritis Dessicans of the Capitellum

Raffy Mirzayan MD

Daniel C. Acevedo BS

Christopher S. Ahmad MD

Neal S. ElAttrache MD

History of the Technique

Primary osteoarthritis (OA) of the elbow is uncommon and accounts for less than 10% of joints involved in primary osteoarthritis.1 Historically, osteoarthritis of the elbow has been reported mostly in elderly men involved in an occupation requiring manual labor. These patients can often tolerate significant motion loss with pain only at end range. In an active patient with work or athletic activities requiring extremes of flexion and extension, end-arc motion loss and pain are not tolerated as well. The previously reported motion arc of 30 to 130 necessary for activities of daily living is frequently not sufficient for these patients.2 This disease of the “active elbow” is the result of repetitive forceful axial loading in hyperextension and hyperflexion, which results in olecranon and coronoid impingement and capsular injury. It is commonly seen in boxers and football linemen, as well as laborers who use jackhammers.

Contractures are a result of degenerative arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and chronic overuse injuries of the elbow.3 Elbow contractures are initially treated nonoperatively with physical therapy. After failure of nonoperative treatment, surgical management is pursued. Traditionally, surgical management involved open surgery in the anterior cubital fossa to perform anterior capsulectomies, distal biceps brachii tendon lengthening, and brachialis muscle transfers.4 Jones and Savoie4 then described a lateral incision technique in 1990 that allowed more complete evaluation and resection of osteophytes of both anterior and posterior parts of the joint. Mansat and Morrey5 described a limited lateral approach known as the column procedure. This procedure elevated muscles of the lateral supracondylar ridge to access the joint for capsulectomy and debridement of the joint. These surgical methods produced some improvement in the range of motion of the elbow. The limitation of these approaches is that it is difficult to reach the posteromedial aspect of the elbow. This is usually the location of osteophytes and posteromedial capsular/ligamentous contractures that can limit flexion. If elbow flexion is severely limited, these procedures will not sufficiently release the elbow to allow increased flexion. It also places the ulnar nerve at risk, as it is not directly visualized and cannot be protected.

Contractures from posterior osteophytic changes were seen to have persistent blockage to extension despite debridement of the posterior aspects of the joint. Kashiwagi6 originally described a procedure that fenestrated the olecranon fossa to create communication between the olecranon and coronoid fossae to alleviate the posterior bony block contributing to elbow contracture. Morrey7 later modified this technique into a procedure described as open ulnohumeral arthroplasty. Others elevated the triceps tendon in order to remove loose bodies and osteophytes from the anterior capsule through the humeral fenestration.8 These techniques were used for successful treatment of elbow contractures and have been recently modified for arthroscopic use.

Hotchkiss9 has described a medial approach to address open release of the stiff elbow. The advantage of this approach is that the ulnar nerve is easily identified and can be released or transposed if necessary. In addition, if flexion is severely limited, the posterior bands of the ulnar collateral ligament can be released to increase flexion. The exposure is performed in the “over-the-top” fashion, where the flexor pronator mass is elevated off the anterior aspect of the medial epicondyle. The anterior band of the ulnar collateral ligament is not transected. The anterior capsule is sharply excised and the posterior compartment can also be addressed.

In the 1990s, arthroscopic surgery became an option for capsular release in elbow contractures, removal of loose bodies,

as well as radial head resections.4,10,11 Arthroscopy offers many advantages for the treatment of elbow contractures including: minimal trauma to surrounding soft tissues, immediate postoperative range of motion exercises, and minimal postoperative scarring.8 This surgical technique requires an experienced surgeon and great attention to detail. The use of arthroscopy to treat elbow contractures is becoming more popular as surgeons are gaining more experience in elbow arthroscopy. O’Driscoll and Morrey12 first described arthroscopy for the removal of loose bodies causing mechanical impairment. More recent studies have described arthroscopic techniques for early osteophyte formation and contractures.4,13 Arthroscopic radial head resection has also been described with satisfactory results.14

as well as radial head resections.4,10,11 Arthroscopy offers many advantages for the treatment of elbow contractures including: minimal trauma to surrounding soft tissues, immediate postoperative range of motion exercises, and minimal postoperative scarring.8 This surgical technique requires an experienced surgeon and great attention to detail. The use of arthroscopy to treat elbow contractures is becoming more popular as surgeons are gaining more experience in elbow arthroscopy. O’Driscoll and Morrey12 first described arthroscopy for the removal of loose bodies causing mechanical impairment. More recent studies have described arthroscopic techniques for early osteophyte formation and contractures.4,13 Arthroscopic radial head resection has also been described with satisfactory results.14

Indications and Contraindications

Indications for arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow include pain, which has failed nonoperative measures including injections, physical therapy, and anti-inflammatory medications. Mechanical symptoms, including locking which is due to loose bodies or uneven surfaces from chondral wear, can be managed arthroscopically. Limitation in range of motion can also be improved arthroscopically. In general, 100-degree arcs of flexion (30 degrees to 130 degrees) and rotation (50 degrees each of pronation and supination) allow most activities of daily living.2 These parameters are not tolerated as well with a younger and athletic population in order to perform their sporting activities. Thus, they should be used as guidelines, but each patient’s needs for range of motion requirements should be assessed individually. When patients have a flexion contracture of greater than 30 degrees, arthroscopic debridement, osteophyte excision with or without capsular release will restore most of the range of motion.

The senior author’s (NSE) personal treatment algorithm for open versus arthroscopic management depends on the amount of flexion present in the elbow and whether the ulnar nerve is involved. If the elbow cannot be flexed greater than 110 degrees preoperatively or there is ulnar nerve involvement, then an open medial, over-the-top approach, as described by Hotchkiss,9 is performed in order to address the ulnar nerve, resect olecranon osteophytes, release the posterior medial capsule, as well as debride coronoid osteophytes and release the capsule anteriorly. Otherwise, arthroscopic management is successful in addressing loose body removal, osteophyte excision, capsular release, and radial head resection. The best results are obtained if an adequate amount of midarc joint space is still seen on preoperative radiographs.

Contraindications to performing this procedure arthroscopically include: late infectious arthritis, severe arthritis with significant, diffuse joint space loss, and ankylosis of the joint. In addition, submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve is a contraindication for anteromedial portal placement.

Surgical Technique

Anesthesia

A general anesthetic is used for this procedure. Muscle paralysis is not required. It is helpful to see muscle twitches if the instrumentation gets too close to a nerve. A preoperative nerve block for pain control is not performed. Since the proximity of neural structures make them susceptible to injury, a nerve block would not allow a surgeon to know if a postoperative deficit is due to nerve injury from the surgery or from the nerve block. If a nerve block is desired for postoperative pain management, it is best performed in the postoperative area, after the patient has been awakened and a thorough neurovascular examination has been performed and documented. A subclavicular block is the block of choice for the elbow, as an intrascalene block does not properly affect the ulnar nerve distribution. If desired, an indwelling catheter is left in place after induction of a nerve block in order to provide continuous pain control. The patient can then be admitted and monitored and started on a continuous passive motion machine with adequate pain

control. Alternatively, the procedure can be done as an outpatient and the catheter is not left in.

control. Alternatively, the procedure can be done as an outpatient and the catheter is not left in.

Patient Positioning

Patient positioning depends on surgeon preference and previous experience with a particular position. Supine, lateral decubitus, and prone positions have all been described and used with good success. The supine position (Fig. 23-1) is useful if the majority of the operation is performed in the anterior compartment. This position allows for easier orientation of anatomic landmarks in the anterior compartment. Supine position is especially useful if an open procedure is anticipated following arthroscopy.

Surface Landmarks and Portal Placement

It is extremely important to draw out anatomic landmarks prior to elbow arthroscopy (Fig. 23-2A,B,C). The course of the ulnar nerve should be palpated and outlined. It is important to examine the patient preoperatively and assess for ulnar nerve subluxation to prevent injury to the nerve. The medial and lateral margins of the triceps tendon, lateral and medial epicondyles, lateral and medial columns (and the medial intermuscular septum), and the radial head are outlined. The anteromedial portal is created 2 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the medial epicondyle. This portal should be placed anterior to the medial intermuscular septum to prevent injury to the ulnar nerve. The direct posterior portal is made through the triceps tendon 2 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon. The posterolateral portal is created at the same level as the direct posterior portal just at the lateral margin of the triceps tendon. The anterolateral portal is created 2 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the radiocapitellar joint. A soft spot portal is also placed in the middle of a triangle drawn from the lateral epicondyle, radial head, and olecranon. This allows improved access to the radial head if a resection is planned.

Arthroscopy

After the landmarks are drawn, the limb is Esmarched and the tourniquet is inflated. The joint is first insufflated with 30 to 40 cc of normal saline (Fig. 23-3). This allows the distention of the capsule and pushes vital neurovascular structures away from the joint line. The arthroscope sheath with a blunt obturator is introduced through the anterolateral

portal. It is preferable to start with this portal since in cases where a submuscular ulnar nerve transposition has been performed, the anteromedial portal cannot be used as the first portal. The outflow on the arthroscope sheath is left open and when a gush of fluid is expressed out of it, intra-articular placement is confirmed. The anteromedial portal is then created by an inside-out or outside-in technique. The anterior compartment is usually difficult to visualize due to thickened scar tissue and synovitis. A shaver is introduced through the lateral cannula and scar tissue and synovitis is debrided. Care should be taken to avoid excessive suction on the shaver. It is often better to remove the wall suction from the shaver and allow drainage by gravity. This will prevent premature excision of the capsule, which can lead to extravasation of fluid into the muscle and poor visualization. It is extremely helpful to place retractors into the anterior compartment to help retract the capsule while work is being completed on other structures (Fig. 23-4).

portal. It is preferable to start with this portal since in cases where a submuscular ulnar nerve transposition has been performed, the anteromedial portal cannot be used as the first portal. The outflow on the arthroscope sheath is left open and when a gush of fluid is expressed out of it, intra-articular placement is confirmed. The anteromedial portal is then created by an inside-out or outside-in technique. The anterior compartment is usually difficult to visualize due to thickened scar tissue and synovitis. A shaver is introduced through the lateral cannula and scar tissue and synovitis is debrided. Care should be taken to avoid excessive suction on the shaver. It is often better to remove the wall suction from the shaver and allow drainage by gravity. This will prevent premature excision of the capsule, which can lead to extravasation of fluid into the muscle and poor visualization. It is extremely helpful to place retractors into the anterior compartment to help retract the capsule while work is being completed on other structures (Fig. 23-4).

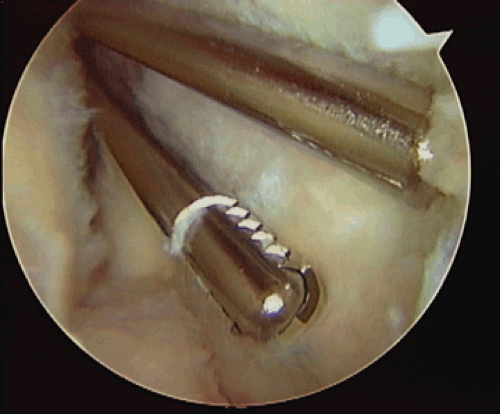

A bur is then used to remove the osteophyte off of the coronoid process (Fig. 23-5). There is a cartilage cap on the osteophyte as well as the coronoid process facing the articular surface, which protects the bur from damaging the articular surfaces of the humerus. The coronoid should be excised to the level of capsular insertion. The cartilage cap is then excised with a shaver or a sharp instrument such as an elevator, Freer, or even the shaver. A capsulotomy is begun from medial to lateral, and capsular release is performed with a shaver. The capsule is shaved off the humeral origin. It is crucial to have very little suction, if any, in order to prevent inadvertently grasping neural structures. The radial nerve can be found at the lateral border of the brachialis muscle.

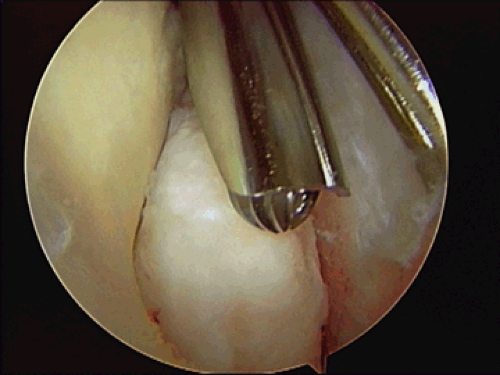

Localized lateral, radiocapitellar tenderness preoperatively and Outerbridge grade IV chondral changes at the time of arthroscopy are indications for a radial head resection (Fig. 23-6). The bur is placed through the lateral portal and excision of the head is started anteriorly and carried posteriorly (Fig. 23-7). The assistant can pronate and supinate

the forearm and deliver the radial head to the bur. The cartilage cap will protect the lesser sigmoid notch against injury from the bur. When the bur no longer reaches parts of the radial head and forearm rotation no longer aids in the resection, accessory portals are used between the lateral portal already present and the soft spot portal. A spinal needle can aid the proper portal placement. The radial head is resected back to the radial neck. The lesser sigmoid notch can serve as a guide to the proper amount of resection (Fig. 23-8). There should be no bone contacting the lesser sigmoid notch.

the forearm and deliver the radial head to the bur. The cartilage cap will protect the lesser sigmoid notch against injury from the bur. When the bur no longer reaches parts of the radial head and forearm rotation no longer aids in the resection, accessory portals are used between the lateral portal already present and the soft spot portal. A spinal needle can aid the proper portal placement. The radial head is resected back to the radial neck. The lesser sigmoid notch can serve as a guide to the proper amount of resection (Fig. 23-8). There should be no bone contacting the lesser sigmoid notch.

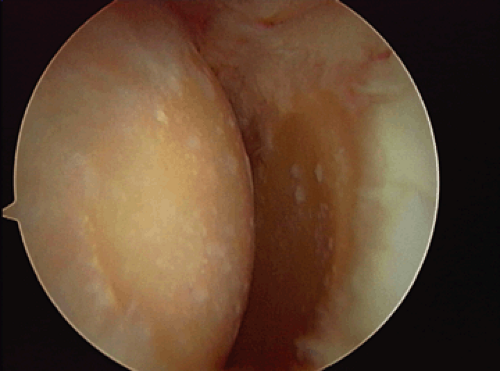

Fig. 23-6. Grade IV chondromalacia of the radiocapitellar joint capitellum to the left and radial head on the right.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|